Baroque Women in Marble as Intimate or Intricate: Comparing Bernini’s Portrait of Costanza Bonarelli to Algardi’s Bust of Maria Cerri Capranica

by Gabriela Diaz-Jones, Art History

How does a male artist translate a female sitter’s presence and appearance into stone? What aspects of the Italian Baroque context could problematize this process of translation? This paper will focus on two Baroque marble busts: one of Costanza Bonarelli by Gianlorenzo Bernini and the other of Maria Cerri Capranica by Alessandro Algardi. The two artworks are borne from nearly opposite contexts. Algardi created a poised, almost lifeless portrait, befitting of its likely funerary purpose. Bernini, on the other hand, carved a work that is stunningly intimate and energetic, gesturing to his secret sexual relationship with Costanza. Bernini’s invention of the “speaking likeness,” the concept of ownership regarding women’s jewelry and clothing during this period, sexual connotations of women’s hair, the myth and symbolism of Medusa, and the legacy of men’s signing images of women as assertions of ownership all come into play when examining and interrogating these works. The tenor of this paper will be that both busts, while they have entirely opposite approaches to depicting women (formal versus intimate, reserved versus dynamic) are still stunningly alike. In both artworks, male artists used sculpture to construct an idealized version of a woman, either moral or seductive. Ultimately both “constructions” are fictions, not reflective of reality but rather, reflections of the role they wanted these women to play (deceased wife of a patron, or lover.) Bernini and Algardi both brought marble to life in the quintessential Baroque style, but the “life” that they imbued into the rock was, without a doubt, not their subjects’ own.

art, history, Baroque, marble, bust, gender

Gianlorenzo Bernini’s bust of Costanza Bonarelli (fig. 1) is a marble sculpture with a captivating mythos. The incredible care with which the marble forms a lifelike rendition of a young woman belies the passionate and ultimately violent love affair that took place between the artist and the subject. The bust itself has been incredibly well-documented, in part because of the massive scandal that unfolded after the bust had already been completed.1 Not commissioned by an individual or guild, this is an example of a sculpture created solely for the artist’s own gratification and artistic experimentation.

Alessandro Algardi’s bust of Maria Cerri Capranica (fig. 2) has a less clear provenance; it was only attributed to Algardi recently, in 2000, upon its sale to the Getty Museum. Though the bust was previously believed to be the work of Giuliano Finelli, archival research into death and marriage documents has revealed a timeline that makes it impossible for Finelli to have carved it. Maria Cerri Capranica, who is unequivocally the subject, lived in Rome until her death in 1643, nine years before Finelli would return to Rome after living for a time in Naples.2 The bust is most likely funerary and was commissioned to adorn her tomb. This can be inferred because non-funerary busts of women were incredibly rare during the Baroque period, with the bust of Costanza being one of very few examples. The two marble busts present two opposed approaches to depicting women: the suffocating perfect image of a noblewoman versus the erotic image of a secret lover. Still, despite their opposite purposes, these works have in common the controlling, at times even violent, dynamic between male artist and female sitter.

Bernini’s Portrait of Costanza Bonarelli, carved in 1636, is life-sized and lifelike. Her hair is rendered in thick waves that frame her round face and create a sense of turbulence as they tumble out of her braided bun (fig. 3). Her eyebrows are just slightly raised, her eyes wide, and her carefully articulated lips are barely parted, suggesting that she is about to speak (fig. 4). McPhee argues that this expression is meant to convey a moment of surprise.3 At her neckline, the fabric ripples in a way that mirrors the loose curls of her hair. The neckline dips low enough to reveal the softness of her clavicle and the beginning of her breasts, but not low enough to be overtly explicit. The garment Costanza wears in this bust was posited by Fraschetti to be a “common nightshirt”, possibly because of its simplicity and the evident lightness of the fabric.4 This portrait is stunning in the vulnerability of its sitter and the intimacy with which she is rendered.

Alternatively, Algardi’s 1640 Bust of Maria Cerri Capranica presents a perfectly articulated young aristocratic woman. Her face is incredibly classical in its abstraction; her impossibly smooth features and blank gaze present an ideal rather than an attempt toward a true likeness of an individual’s physiognomy. Her hair alternates from smoothed waves on the top of her head to the incredibly tight and assiduously carved curls that frame the sides of her face. Her costume’s lace mantel is elaborate and precise. The ribbon above her pendant is delicate, and the swirling beads of her necklace are at some points completely free-standing from the rest of the bust (fig. 5). Even the pattern on the fabric of her bodice is painstakingly etched into the marble. There is an incredible stiffness to this portrait, and the intricacy with which the sitter and her costume are treated evoke a profound sense of being forever smothered under multiple layers of fabric, lace, and ornamentation. The blank stare and austere expression are certainly in part a result of the bust’s purpose as a funerary monument. Still, the delicate cloth and beads that form thick strata on the subject feel like they speak to something more than the memorialization of a woman’s death.

Figure 5. Algardi, Alessandro. Bust of Maria Cerri Capranica (det. of necklace), 1640, marble, 90 x 61.3 x 29.2 cm, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California (Artstor, ITHAKA).

In 1951, Rudolf Wittkower coined the term “speaking likeness” as a modality of describing Bernini’s sketch of Scipione Borghese and the subject’s incredibly dynamic expression, which suggests that he is in a moment of conversation. The phrase has since developed into a form of shorthand for the exceptional liveliness Bernini lends to the subjects he depicts, be it in a painting, sketch, or sculpture.5 The category certainly applies to his sculpture of Costanza; her mouth is opened gently, enough to reveal the contours of both rows of teeth. This pursuit of capturing a moment of spontaneity was, in a way, also a pursuit of capturing the true essence and individuality of the sitter: Bernini’s son, Domenico Bernini, wrote in his biography of his father that the excellence of the bust, as well as a painting by his father of Costanza (which is not extant), is a testament to his father’s feelings for her.6

The younger Bernini wrote that his father’s depictions of Costanza “revealed how much he was in love with the original.”7 While this note could be interpreted as a son’s efforts to lighten the shadow of scandal looming over the biography of his father, it represents much more the mythologization of a damaging affair. Domenico’s passing reference to his father’s relationship gestures to a legacy of the portrayal of wives and lovers in the work of male artists. This dynamic between artist and subject/lover will be discussed later, toward the end of this article. It is interesting to consider how the emotionality of the relationship between artist and subject could impact the effectiveness of the resultant image. In this case, Bernini’s relationship with his subject led to a bust that represents a multiplicity of metamorphoses. Costanza Bonarelli, as Bernini memorialized her, is perpetually moving from silence to speech, acquaintance to lover, from living flesh and flowing hair to marble. He conquered the stillness of stone and shaped it into a stunningly dynamic composition.

Where Costanza Bonarelli seems to be on the verge of speaking, Maria Cerri Capranica appears perfectly silent. Her face is still and serene, fitting of a tomb monument. The bust could even be interpreted to depict its sitter more in death than in life. Her eyes read as blank, in part because Algardi made little attempt to represent the pupil or iris through carving into the surface of the eye. Contrastingly, Costanza’s eyelids actually sit over the eyes with a sense of weight and gravity. Her eyes seem to rest within the orbital bone, and thus peer out at the viewer with a greater gravitas. Maria’s eyes, on the other hand, are wide open in an uncanny way, mirroring classical sculpture’s blank gazes. Her eyelids, mouth, and to some extent her nose, are also all abstracted. They represent the idea of these parts rather than the physiognomy of the subject. However, the shape of her face and chin, her jawline, and the incredible distinctiveness of her hair suggest a very subtle sense of individuality.

Yet overall, the bust is not particularly lifelike and is more an allegorical image of Maria than an authentic one. Assuming the bust was indeed produced upon or after the sitter’s death, the luxuriance of the subject and her costume take on a new meaning. Simons writes that during the Renaissance, the costume of women in portraits had an “emblematic significance” conveying the social standing of a woman’s natal family and family incurred through marriage. An instance in 1490 of a father’s writing in his will that the jewelry he gave to his daughter should be remitted to his estate after his daughter’s death colors the significance of Maria’s finery.8 Though it predates the bust of Maria by over a hundred years, this anecdote speaks to the significance of women’s appearance, and more specifically their costume, in art. The finery Maria wears in the bust was not her own; it would have belonged to her father or husband and was more a communication of their status than hers. Maria’s ornamentation expresses what she had in life and lost in death: two prestigious families (she was a Cerri by birth and Capranica by marriage) and the material wealth that the men in those families possessed. However, the bust does not speak to another loss her death incurred: the loss of an individual, with an ethos. Algardi’s portrait is a visual document commemorating the life she lived: a life that her family ensured was comfortable yet was ruled by strict social conventions. It is important to consider that the bust was most likely carved after Maria’s death.9 Therefore, her blank eyes and otherworldly, almost generic face are in part due to the context. Still, the delicate layers of adornment that envelop her like a sarcophagus are striking and should not be written off as the typical stoic effect of a tomb monument.

At first glance, Maria’s hair as depicted in her bust is her most striking feature. The tight spirals, partly hollow, are not necessarily lifelike. However, this complex form speaks to the talent of the artist, who was able to achieve this elaborate shape not just in a few curls framing her face, but in each curl on her head. Giorgio Vasari singled out the rendition of hair and beards as key criteria upon which to determine an artist’s ability, especially regarding sculpture.10 Particularly in the context of the paragone, these incredibly delicate subject matters functioned as a sort of assessment for sculptors, an ordeal to be overcome but also a way to assert oneself as a master. So, in choosing to render Maria’s hair as tightly curled and loose around her face, and in lifting a portion of her necklace off her bodice, Algardi is making a very clear statement about his capability as a sculptor, but more importantly, as an artist.

Bernini’s approach to Costanza’s hair has proved more controversial over time. At the time he first sculpted the bust of Costanza, an unknown writer noted that her hair appeared “coarse.”11 This was undoubtedly an insult, especially when the criteria for sculpted hair at the time, as first outlined by Vasari himself was “a certain softness…the greatest featheriness and grace given to them that the chisel can convey.”12 Within the context of Seicento Italy, women’s hair held sexual significance. During the Renaissance, Dominican friar Giarloma Savonarola complained about young women attending mass with uncovered heads, out of fear that attendants, priests, (and even the angels in heaven) would be distracted by female hair, which as Lugli vividly explains “entrapped men’s gazes like a magical lasso.”13 The lasso metaphor is interesting, and implies that movement or motion is the impetus for seduction; therefore, Maria’s perfectly molded, motionless helmet of hair would be less tempting than Costanza’s much more active curls.

Figure 6. Bernini, Gianlorenzo. Medusa, 1630-1644, marble, 68 cm, Musei Capitolini, Rome, Italy (Artstor, ITHAKA).

Bernini’s approach to Costanza’s hair is not an endeavor toward lightness or softness. He parts it into thick sections that move like waves across her head and around her face. Her braided bun is delicate and feminine, but the way the hair appears to be falling out of it into tendrils by ears suggests movement, activity, something to have loosened her braids. It is through this interpretation that McPhee argues that the dynamism of her hair adds to the erotic undertone of the bust. The dense and animated sections of Costanza’s hair are, in some ways, similar to the snake hair of the 1635 bust of Medusa (fig. 6), also by Bernini. The faces of the two busts are similar as well, with their gently parted lips, soft jaw, full cheeks, and incredibly emotionally expressive eyes. Avery was the first to draw this parallel, explaining that the anguished expression on the face of the Medusa may be a projection of Bernini’s guilt at the painful end of their love affair. Then, Avery goes on to posit that the purpose of the Medusa may have been for Bernini’s artistic practice and interest in allegorical sculpture, something he carved for himself, “just as he had done the head of Costanza Bonarelli.”14

Most evident of their similarities is their marble “hair,” which in both busts feels turbulent, and unruly. McPhee notes that Costanza’s hair has been interpreted by many as sensual and thus, suggestive of the sexual relationship between her and Bernini.15 Within the sculptures of both Medusa and Costanza, Bernini uses the wildness of the hair to characterize the female subjects as ungovernable. It would have been easier for him to smooth Costanza’s hair into the braided bun, showing her in a more presentable, orderly condition. Instead, he carved her hair with the energy with which he later carved the serpents that frame Medusa’s face: she is in an untamed, therefore erotic state. Haughey describes the duality of petrification and portrayal that comes into play when artists depict Medusa; artists are playing the role of Medusa herself when they sculpt her, turning her to stone like one of her victims. Costanza does indeed look like she has been frozen in rock, interrupted in a moment of speaking.16

Like her hair, Costanza’s clothing in the bust is a modality through which Bernini expresses his intimate relationship with her and adds a sensual energy to the marble. The fabric at her neckline, which dips into a V-shape right above her breasts, is visually similar to what is worn by the sitter in Verrocchio’s Portrait Bust of a Lady with Flowers (fig. 7). It has been proposed that the young woman in this 1475 bust is wearing a camicia, a nightgown that would have been incredibly private, the layer of clothing worn closest to the skin. Interestingly, this article of clothing was also worn by those acting as nymphs in dramatizations of mythological scenes.17 This context compounds the already obvious eroticism of the bust, adding an even more sensual element: the fact that the sculptor would have seen the sitter in such an intimate state to create the likeness, along with the symbolic and mythic sexuality of nymphs.

Figure 7. del Verrocchio, Andrea. Portrait Bust of a Lady with Flowers, 1475, marble, 61 cm, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, Italy (Artstor, ITHAKA).

As in the Verrocchio bust, the thin fabric of Costanza’s camicia adds to the overtones of “sensuous beauty.”18 But unlike Costanza, the subject of the bust by Verrochio has her hands propped in front of her chest in an echo of the Venus pudica gesture. While the thin fabric clings to her skin, she attempts to prevent an intimate exposure. And in the same hands, which she places in front of her to protect her modesty, she holds a small bunch of flowers. These are symbolic of innocence, purity, and virginity. She wears the same costume as Costanza, but any indecency is tempered by her hands, which pretend to hide what the sculptor has already carved in incredible detail. However, in Bernini’s bust, Costanza’s hands are not depicted. Yet the fabric that drapes across her shoulders is light and gauzy, moving in ripples suggestive of thin cotton or linen, not a stiff and therefore formal material. On the left side of her body, the sculptor carved the dip of the neckline to fold over the rest of the fabric, revealing even more of her bust.

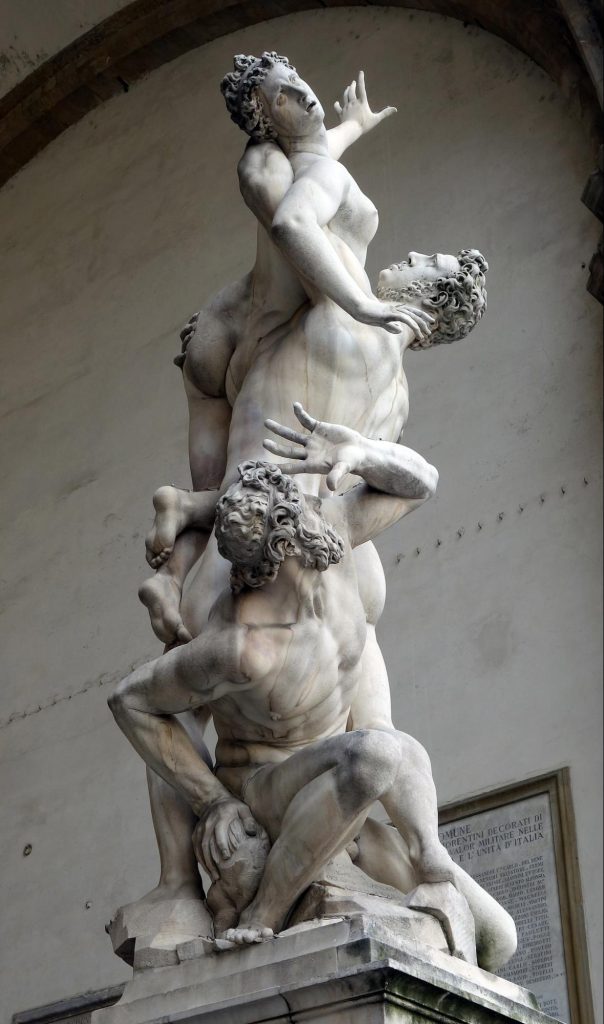

Giambologna’s Abduction of a Sabine Woman (fig. 8) is a towering composition, with a tremendous amount of energy contained within its three figures like tension in a spring, ready to snap. Whether it represents an abduction, a rape, or the lifting of the female figure up in the air in a sort of rapture, there is a woman at the center of the sculptural group having something done to her that she does not want, and is struggling against.19 Regardless of the narrative Giambologna had in mind while carving this group, either the mythological abduction of the Sabine women or something more ephemeral and allegorical, some elements of the composition are certain and do not leave room for debate (as the contested theme of the sculpture has been debated). There is a woman who is being lifted and grabbed violently, and a man pushed to the bottom of the sculpture who is attempting, but is ultimately helpless, to stop this. On the rocky outcropping underneath this second male figure, who is being trampled by the standing male, is Giambologna’s carved signature. Previous literature has stated the inscription was situated “near the genitals” of the fallen man (who is possibly the woman’s father), “at the base.”20 The signature is carved into the rocks upon which the man sits as he leans back (fig. 9), directly underneath his genitals, between his two tensed thighs. Weil-Garris makes a loose speculation as to what may have motivated this atypical placement, and what greater significance it may hold, writing that it may be a signal towards “the artist’s role as creative or generative” and suggests the older male figure may be a self-portrait of the artist. Thus, the groin near the signature would be symbolic of Giambologna’s own.21

Figure 10. Raphael, La Fornarina (The Baker Girl), 1518-1519, oil on wood, 86 x 58 cm, Galleria Nazionale d’arte Antica, Rome, Italy (Artstor, ITHAKA).

Another notable example of an artist including their name within a composition of a young nude woman is Raphael’s La Fornarina (fig. 10). In this painting, a young baker girl sits in front of a dark, partly obscured background of foliage. The translucence of her shift billows around her left forearm, and her stomach. Her left arm is lifted for her hand to cup her breast, and across the other arm is a thin gold band with Raphael’s signature delicately painted on. The armband is likely inspired by extant works of antiquity, which depict the goddess Venus and the Three Graces wearing similar bands. However, the inclusion of the artist’s name on this piece of jewelry, especially close to the sitter’s exposed breast, is certainly out of the ordinary. Bernstein’s interpretation of the autograph is that it expresses Raphael’s awareness of the new frontier of erotic images of nude women, as Renaissance artists began sketching and painting from nude female models.22 Bernstein believes the painting is likely a portrait of a real woman, who sat for Raphael. It has even been suggested that the sitter may have been Raphael’s lover.

Bernstein argues that, in emblazoning his name on the painted woman’s arm, Raphael is articulating that “he, the male artist, is the master and creator of whatever he desires to paint.”23 I contend that by interrupting the illusionistic painted world of the portrait with his name, Raphael is symbolically communicating that he possesses the woman he has painted, just as he owns the wood panel of the painting itself. So, in Bernstein’s words, Raphael is indeed the “master” of this painted woman, in a way that doubtlessly paralleled his power over the real world of flesh and blood, not just the world of paint and wood. Interestingly, the bust of Costanza was once referred to as Bernini’s “Fornaia” (“baker girl”) during the 18th century. The writer drew a parallel between the bust and Raphael’s portrait (fig. 10) because the painting was well-known and both artworks may share a subject matter: the artist’s lover.24 Giambologna and Raphael, by associating their names and artistic identities with sexual elements of their work, each characterize their work as a sexual act. In a similar way, euphemisms for sex traditionally include ideas of “taking” or “having” somebody, particularly a woman. Giambologna’s sculptural group connects his carved name, and therefore his identity as a sculptor, near the genitalia of a male figure who is situated within a scene of sexual violence and raptio, literally an abduction or “taking,” violently seizing possession of someone. The artist may have considered the younger male “conquering” the woman to parallel his talent in “conquering” the stillness of marble and turning it into something dynamic, and active. To depict someone in marble or paint can be seen as a way of “having” them, or at least a representation of them.

Like Raphael’s painted signature or Giambologna’s carved one, Bernini’s distinctive style and innovation of speaking likeness act as his signature. He does not need to include his name by Costanza’s breast as Raphael did; his work speaks for itself. Maria is not marked with Algardi’s name. She does not need to be because at the base of the bust is the Cerri family coat of arms: a turkey oak. It is unclear whether the bust was intended to be placed in the Cerri family chapel in the church of Il Gesú or in the Capranica family chapel in the Basilica of Santa Maria sopra Minerva; the former is considered to be more likely than the latter.25 What is clear, though, is which family she was buried with. Her burial site is in the Capranica chapel, the eternal resting place of her husband’s family.26

Bernini did not keep the bust he made of Costanza after their love affair came to a violent conclusion. In 1638, Gianlorenzo Bernini discovered that Costanza had taken on a new lover: his younger brother, Luigi Bernini.27 Upon receiving this news, the elder Bernini sent a messenger to slash the face of Costanza. At the time, one’s face was considered to reflect one’s honor, so to wound someone’s face was to curse them with a mark of shame and scorn (in the form of a scar) that would be a part of them for the rest of their life.28 It is interesting to consider this assault by proxy as a sort of “carving,” and Bernini was no doubt enraged that the flesh-and-blood Costanza was not more like the perfect marble replica he created and owned. He gave away the bust soon after his relationship with her ended. Eventually, it came into the possession of Francesco D’Este, the Duke of Modena, another man who likely enjoyed the sexually charged sculpture, and its controversial history.29

Both busts were the property of the men who created or commissioned them, and this possession shaped the way that the two subjects were translated onto a piece of marble. Therefore, both artworks are, through inverse modalities, literal object-ifications of the women represented. Frozen in time by the artist, like Medusa’s victims, these women are ideal in opposite ways, like different sides of the same coin. Each is ideal in their lover’s or family’s eyes: Costanza is erotic, Maria is perfect, and both are silent.

Images

Figure 1. Bernini, Gianlorenzo. Portrait of Costanza Bonarelli, 1636, marble, 72 cm, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, Italy (Artstor, ITHAKA).

Figure 2. Algardi, Alessandro. Bust of Maria Cerri Capranica, 1640, marble, 90 x 61.3 x 29.2 cm, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California (Artstor, ITHAKA).

Figure 3. Bernini, Gianlorenzo. Portrait of Costanza Bonarelli (profile view), 1636, marble, 72 cm, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, Italy (Artstor, ITHAKA).

Figure 4. Bernini, Gianlorenzo. Portrait of Costanza Bonarelli (det. close view of the face), 1636, marble, 72 cm, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, Italy (Artstor, ITHAKA).

Figure 5. Algardi, Alessandro. Bust of Maria Cerri Capranica (det. of necklace), 1640, marble, 90 x 61.3 x 29.2 cm, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California (Artstor, ITHAKA).

Figure 6. Bernini, Gianlorenzo. Medusa, 1630-1644, marble, 68 cm, Musei Capitolini, Rome, Italy (Artstor, ITHAKA).

Figure 7. del Verrocchio, Andrea. Portrait Bust of a Lady with Flowers, 1475, marble, 61 cm, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, Italy (Artstor, ITHAKA).

Figure 8. Giambologna, Abduction of a Sabine Woman (side view), 1583, marble, 409 cm, Loggia dei Lanzi, Florence, Italy (Smarthistory).

Figure 9. Giambologna, Abduction of a Sabine Woman (det. inscription), 1583, marble, 409 cm, Loggia dei Lanzi, Florence, Italy (Smarthistory).

Figure 10. Raphael, La Fornarina (The Baker Girl), 1518-1519, oil on wood, 86 x 58 cm, Galleria Nazionale d’arte Antica, Rome, Italy (Artstor, ITHAKA).

Bibliography

Avery, Charles. Bernini: Genius of the Baroque. University Park: Little, Brown and Company, 1997.

Bacchi, Andrea. “A Proposed Attribution to Alessandro Algardi: Maria Cerri Capranica at the J. Paul Getty Museum.” Sculpture Journal 20 no. 2 (2011): 117–27. http://dx.doi.org/10.3828/sj.2011.12.

Bernini, Domenico, and Gian L. Bernini. Life of Gian Lorenzo Bernini. Edited by Franco Mormando. Translated by Franco Mormando. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2011.

Bernstein, Joanne G. “The Female Model and the Renaissance Nude: Dürer, Giorgione, and Raphael.” Artibus et Historiae 13 no. 26 (1992): 49-63. https://doi.org/10.2307/1483430.

Cole, Michael. “Giambologna and the Sculpture with No Name.” Oxford Art Journal 31 no. 3 (2008): 337-359. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20542849.

Haughey, Patrick. “Bernini’s ‘Medusa’ and the History of Art.” Thresholds, no. 28 (2005): 76-154.

Hendler, Sefy. “Pelo sopra pelo: sculpting hair and beards as a reflection of artistic excellence during the Renaissance.” Sculpture Journal 24 no. 1 (2015): 5-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.3838/sj.2015.24.1.2.

Hess, Catherine, Anne-Lise Desmas, Andrea Bacchi, and Jennifer Montagu, eds. Bernini and the Birth of Baroque Portrait Sculpture. J. Paul Getty Museum, 2008.

Johnson, Geraldine. “Idol or Ideal? The Power and Potency of Female Public Sculpture.” In Picturing Women in Renaissance and Baroque Italy eds. Geraldine Johnson and Sara Matthews Grieco, 222-245. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Luchs, Alison. “Verrocchio and the Bust of Albiera degli Albizzi: Portraits, Poetry and Commemoration.” Artibus et Historiae 33 no. 66 (2012): 75-97. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23509745.

Lugli, Emanuele. “The Hair is Full of Snares: Botticelli’s and Boccaccio’s Wayward Erotic Gaze.” Mitteilungen Des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 61, no. 2 (2019): 203–33. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26922482.

McPhee, Sarah. Bernini’s Beloved: A Portrait of Costanza Piccolomini. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012.

Simons, Patricia. “Women in Frames: The Gaze, the Eye, the Profile in Renaissance Portraiture.” History Workshop no. 25 (1988): 4–30. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4288817.

Weil-Garris, Kathleen. “On pedestals: Michelangelo’s David, Bandinelli’s Hercules and Cacus and the sculpture of the Prazza della Signoria.” Romisches Jahrbuch für Kunstgeschichte Wien 20 (1983): 377-415.

Notes

- Sarah McPhee, Bernini’s Beloved (Yale University Press 2012). 1. ↩︎

- Andrea Bacchi “A Proposed Attribution to Alessandro Algard,.” Sculpture Journal 20 no. 2 (2011), 120. ↩︎

- Sarah McPhee, Bernini’s Beloved (Yale University Press 2012). 3. ↩︎

- Andrea Bacchi, Anne-Lise Desmas, Catherine Hess, Jennifer Montagu, eds. Bernini and the Birth of Baroque Portrait Sculpture (J. Paul Getty Museum 2008), 23. ↩︎

- Ibid., 20. ↩︎

- See “Costanza Bonarelli”, 2006, by McPhee (pp. 315-318) for information on the existence of a painted double portrait by Gian Lorenzo Bernini of himself and Costanza Bonarelli. ↩︎

- Domenico Bernini, The Life of Gian Lorenzo Bernini, ed. Franco Mormando (University Park: The Pennsylvania University Press, 2011), 113. ↩︎

- Patricia Simons, “Women in Frames: The Gaze, the Eye, the Profile in Renaissance Portraiture,” History Workshop 25 (1988): 9. ↩︎

- Bacchi, “A Proposed Attribution”, 124. ↩︎

- Sefy Hendler, “Pelo sopra pelo: sculpting hair and beards as a reflection of artistic excellence during the Renaissance,” Sculpture Journal 24, 1 (2015): 12. ↩︎

- Ibid, 18. ↩︎

- Ibid, 12. ↩︎

- Emanuele Lugli, “The Hair is Full of Snares: Botticelli’s and Boccaccio’s Wayward Erotic Gaze.” Mitteilungen Des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 61, no. 2 (2019): 206. ↩︎

- Charles Avery, Bernini: Genius of the Baroque (University Park: Little, Brown and Company, 1997), 92. ↩︎

- McPhee, Bernini’s Beloved, 41. ↩︎

- Patrick Haughey, “Bernini’s ‘Medusa’ and the History of Art,” Thresholds, no. 28 (2005): 81. ↩︎

- Alison Luchs, “Verrocchio and the Bust of Albiera degli Albizzi: Portraits, Poetry and Commemoration,” Artibus et Historiae 33, no. 66 (2012): 86. ↩︎

- Ibid, 86. ↩︎

- Michael Cole, “Giambologna and the Sculpture with No Name,” Oxford Art Journal 31, no. 3 (2008): 348. ↩︎

- Geraldine Johnson, “Idol or Ideal? The Power and Potency of Female Public Sculpture,” in Picturing Women in Renaissance and Baroque Italy ed. by Geraldine Johnson, and Sara Matthews Grieco (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 242. ↩︎

- Kathleen Weil-Garris, “On Pedestals: Michelangelo’s ‘David’, Bandinelli’s ‘Hercules and Cacus’ and the Sculpture of the Piazza Della Signoria,”Römisches Jahrbuch für Kunstgeschichte 20 (1983): 414. ↩︎

- Bernstein, Joanne. “The Female Model and the Renaissance Nude: Dürer, Giorgione, and Raphael,” Artibus et Historae 13 no. 26 (1992): 58. ↩︎

- Ibid, 60. ↩︎

- McPhee, Bernini’s Beloved, 146. ↩︎

- Bacchi, “A Proposed Attribution,” 125. ↩︎

- Ibid, 125. ↩︎

- McPhee, Bernini’s Beloved, 1. ↩︎

- Ibid, 44. ↩︎

- Ibid, 15, 62. ↩︎

Acknowledgments

To my sister, Julia Grace Jones. Thank you!

Citation Style: Chicago, 17th Edition