The Floor Mosaics from the House of the Faun:

An Exploration of Theme and Perception

by Charlotte Taylor, Art History

Abstract: This paper examines the way in which the figural floor mosaics in the House of the Faun functioned individually and collectively in the viewer’s experience of the overall villa. While the Alexander mosaic has been the locus of much analysis in the Pompeiian residence, bringing this work into context within the floorplan and the other mosaics creates a more accurate assessment of their impact on the ancient Roman. By elucidating the research on the villa’s design plan and the mosaics’ placement, we may bring them out of the museum and return them back into their intended environment; that is, to be seen underfoot and as part of a larger whole. This paper will then explore the disparate subjects of the mosaics, from Nilotic landscapes to Dionysiac theater masks, and how this variability contributes to the richness of the home. Each mosaic indicates the function of the space it occupies, from elevated discussion in an exedra to fine dining in a triclinium, visually transporting visitors into a new reality. The final section of the paper will discuss how the physical act of walking on and around these mosaics both disrupts this illusion and reinforces it. The viewer both understands the falseness of the image which he steps upon, and also becomes involved in the mosaic, moving through the space informed by its placement in the room. Visitors shift from passive audience to active participants in their physical interaction with these mosaics and even more so when they partake in academic or casual discussion inspired by them. Taken together, the diverse figural mosaics found in the House of the Faun illustrate the height of mosaic craftsmanship, luxurious villa lifestyle, and the inherently experiential aspect of such artworks that must be reclaimed and reimagined.

Pompeii, Rome, mosaics, villa, exedra, triclinium

“…the moment we set our foot in Pompeii, we are in a world of illusions.”

– Thomas Gray (The Vestal or, A Tale of Pompeii, 1830, vi)

Introduction

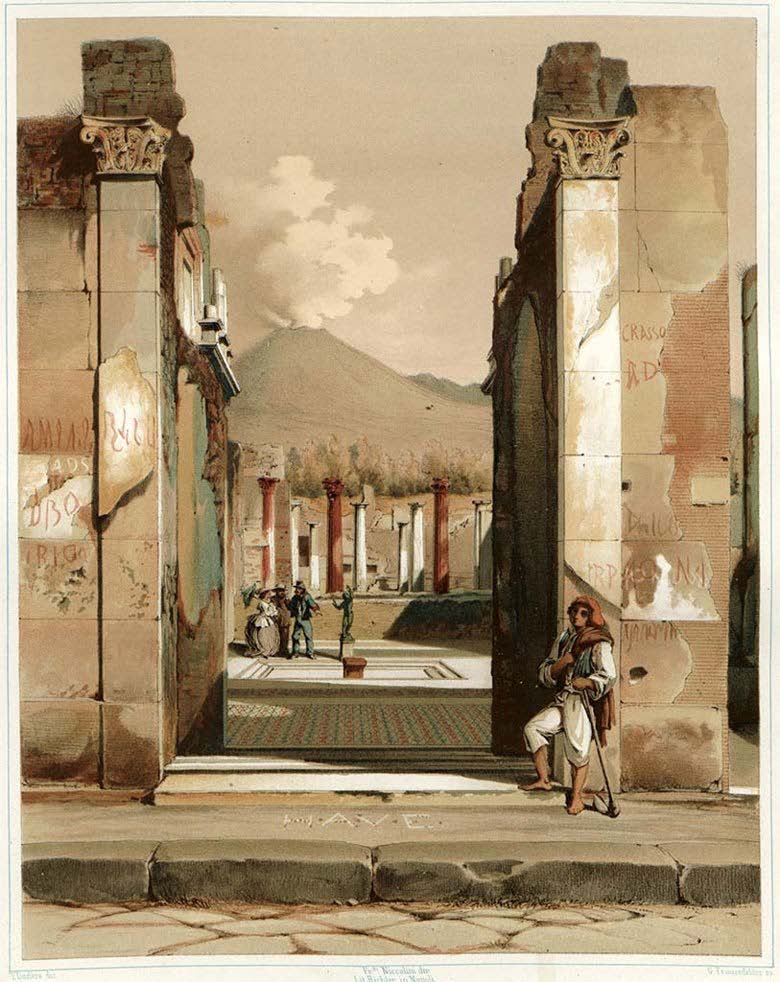

Among the elite houses of Pompeii, the House of the Faun stands out as one of the greatest, with its high level of craftsmanship particularly in its mosaics. A home of such grandeur, occupying an entire insula,1 would have certainly been the property of a Roman aristocratic family who sought to convey their status in the interior space of the villa.2 The grand, detailed mosaic scenes found in what remains of the structure illuminate this commitment to reflecting one’s wealth in interior decoration. Even more so, it has long been believed that some of the mosaics originated in Greek workshops, rather than by the hands of local Roman craftsmen; certain elements of the style, subject matter, and material support such a belief.3 Even if they were not original Greek mosaics, but Roman recreative copies, these carefully executed ornaments evoked Greek luxuria4 and a convergence of wealth and cultural knowledge.5 Thus, the house’s owner likely chose these emblemata6 carefully, with both a particular Hellenistic tradition of mosaic flooring in mind, as well as subject matter that referenced original Greek paintings.7

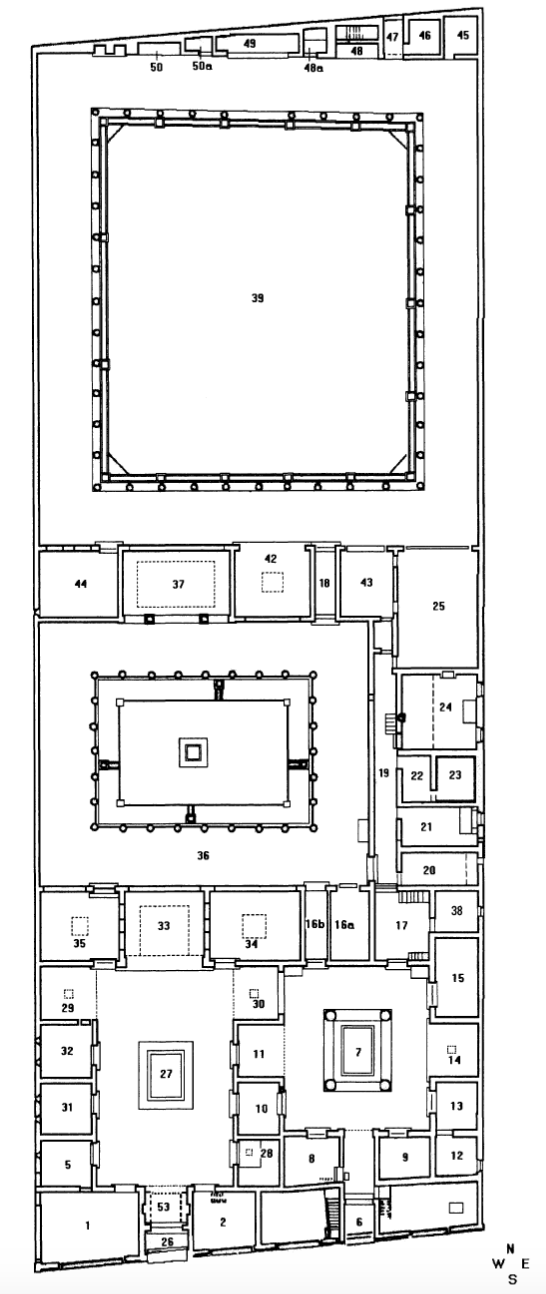

Built in multiple phases throughout the second century BC, the House of the Faun is composed of two atria, two peristyles, an exedra,8 and many various service corridors and dependent rooms.9 The initial building phase during the first half of the second century BC resulted in the two atria and the first peristyle. Later renovations toward the end of the second century added an exedra facing a second peristyle. These additions raise the question: to what end were these designs realized? How did the architectural design and the resulting flow of each room into the next contribute to the perception of the owner’s status? And, given this architectural context, what implications does the house’s decoration, namely the floor mosaics, have for the visitor’s experience? This paper seeks to examine whether or not the floor mosaics within their context of the house establish a specific narrative, individually or as an ensemble, and the way in which visitors, both ancient and modern, might understand these mosaics.

Though the house was completed over the course of a century, its architects clearly conceived of the home as one unit with a coherent pattern in design.10 This design aims to unite the principal rooms of the house in a single vista down the main axis and communicate the shift from public to private spaces. As the visitor moves further within the home, this hierarchy of space is demonstrated architecturally, with the grand second peristyle in the back of the house serving as the pinnacle of displayed wealth and seclusion. The ancient Roman could observe a wide range of flooring in the House of the Faun, from abstract, geometric mosaics to figural, representational scenes. Both kinds contributed to the way in which the guest understood his movement through the home’s different spaces. However, the focus of this paper is on the opus vermiculatum11 representational mosaics. Considering the Alexander mosaic (the most famous among these) alongside the accompanying smaller emblemata, no program may be derived from widely varied symbolism. Instead, they compromise a patchwork of various scenes, some united in theme and some not — a mosaic of mosaics. To capture their full range of meaning, these works should be understood together in their physical, spatial context within the home itself just before the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in 79 AD.12

While the owner certainly had themes in mind regarding the decoration of this extravagant home, a simple, collective statement which threads through each of the mosaics would oversimplify reality. Rather, they evoke various Hellenistic mythological and political associations, including depictions of a historical battle, Dionysiac symbols, and naturalistic landscapes, that reflect the lifestyle of elite Roman nobility. Considering their place within the home, these works conjure imagery that guide and inform the visitor’s movement throughout each space. By examining this experiential aspect of the House of the Faun’s floor mosaics, a recontextualization may illuminate their original intent and perception for the modern viewer.

Excavation History

From 1830 to 1832, the initial discovery and excavations of the House of the Faun revealed a building of palatial size, along with the highest quality First Style wall paintings and opus vermiculatum floor mosaics in the entirety of Pompeii.13 Retrieving and restoring these decorative elements have been the primary focus of excavations around the villa. Originally excavated under Carlo Bonucci, later excavations by the Deutsches Archäologische Institut began in the early twentieth century.14 From the results of these German excavations, Adolf Hoffmann in 1985 published his conclusions regarding the house’s architectural history. Hoffmann posited this theory of two distinct building phases throughout the second century BC, starting in 180 BC.15 However, another theory suggests three different building phases instead, emphasizing that only with the third and final phase around 80 BC were these floor mosaics included.16

Shortly after their discovery, the mosaics were removed from their original location and transferred to museums. Specifically, the Alexander mosaic, which depicts a battle against the Persian army led by Darius III, was transported to the Royal Bourbon Museum in 1843 after much debate regarding whether to detach it from the house itself or not.17 Because of this removal, very little is known about the original installation of the mosaic. The Alexander mosaic was later moved to the National Archaeological Museum of Naples, where it and the other primary mosaics of the villa currently reside.

Visual Analysis and Description of the Mosaics

Tragic Masks and Cornucopia Elements

The first figural mosaic that the guest would have seen would be the two tragic Greek theater masks which occupy central focus in the threshold separating the fauces18 from the first atrium on the left side. Their eyes look upward — that is, toward the atrium — and are adorned with long curling locks. They are set against a rich festoon display, including fruits, foliage, ribbons, and bands with geometric patterns on them. The inclusion of masks, especially in a threshold space, evokes the performative element of the Roman social sphere, which is further heightened in the grandeur of the atrium where the pater familias19 would greet guests.

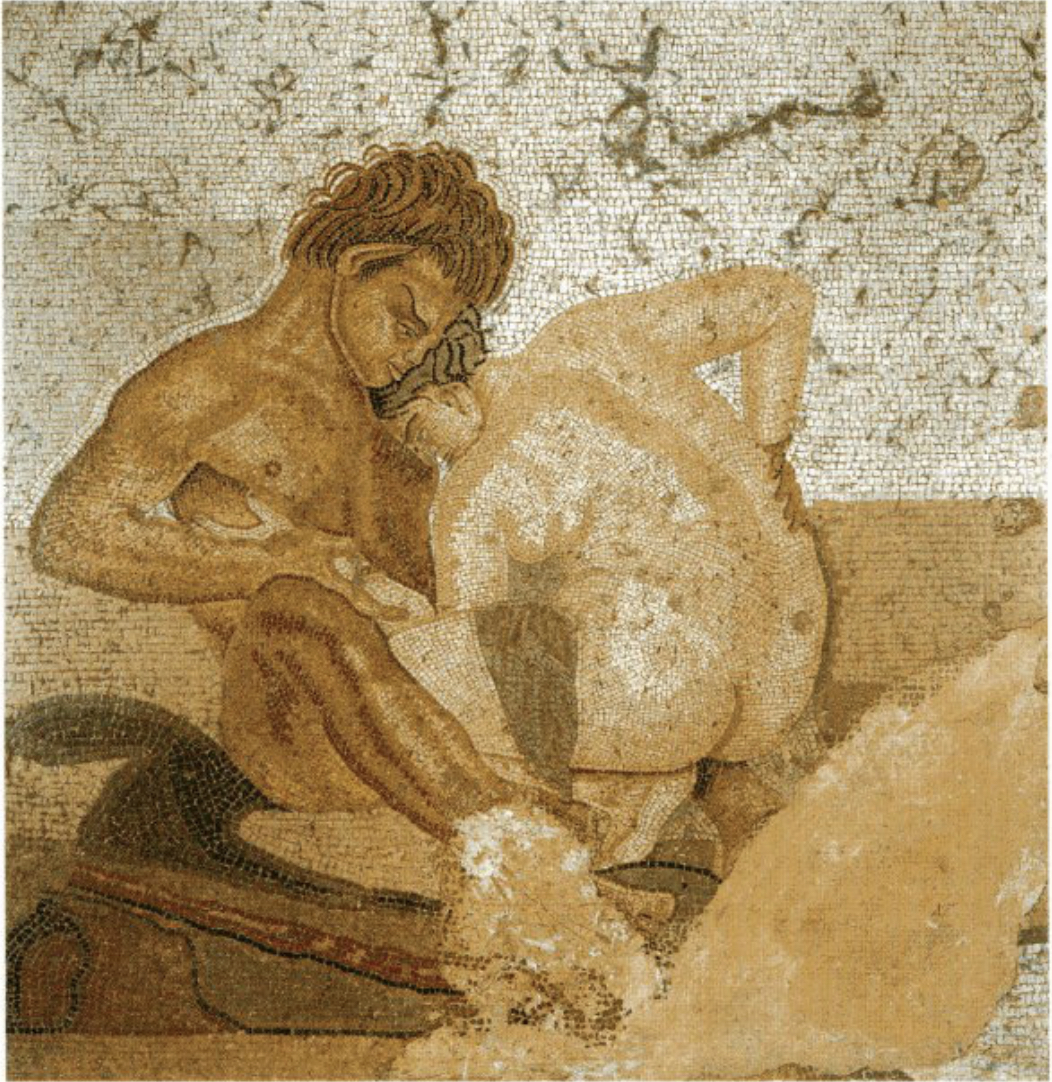

Symplegma

The small mosaic depicting two lovers, a satyr and maenad, was found in a cubiculum20 to the right of the first atrium. The maenad crouches, facing her partner so that only her arched, bare back and slight profiled face remain visible to the viewer. She bends one arm to rest on her right hip while she clutches the chest of the satyr with her other. The satyr has tall, pointed ears and bends to rest his head atop of his partner’s, grasping her hand in return. The intimate scene of nude figures embracing one another was more fitting for this private room and continues the Dionysian theme evoked by the masks. Such images were part of a larger motif of eroticism in Pompeii and associated with religious festivals, such as the Floralia.21

Aquatic Scene

In a triclinium22 off of the first peristyle, a smaller square mosaic exhibits a great array of fish species in an aquatic scene, from an octopus to a lobster to mollusks. The lower quarter of the square is marked by a horizon line dividing the water from the sky with a rocky island jutting out above the water’s surface on the left side of the image. Greenery and exotic flowers outline the border of the whole image. This subject matter is fitting for a summer dining room, with images of edible sea creatures that might be served on the very tables atop this mosaic. Despite this defined sense of space and landscape, the array of sea fauna seems detached from the background and placed both above and below the water line, defying gravity; this reveals the explicitly horizontal nature of the mosaic, as it was intended to be seen on the floor.

Young Dionysius

In a triclinium facing the smaller peristyle, a square mosaic is framed by one band of a simplified wave pattern and another band of Greek masks surrounded by a festoon. At the center, it explicitly depicts a young, winged Dionysius riding a hybrid animal, with the body of a tiger and the head of a lion. His temple is wreathed with ivy and grape leaves and he simultaneously tames the animal with a firm grip on the reins. He lifts his cup of wine, either in offering or in preparation to partake in the drink himself. This image appears more autumnal and offers guests another dining option.

Nilotic Scene

The threshold from the first peristyle into the exedra which houses the Alexander mosaic is divided into three mosaics because of the placement of two columns at the front of this room. The center panel depicts a scene of various animals swimming in a body of water, evoking associations with the Nile due to its connection to Alexander and his conquest of Egypt, as well as to the specific animals displayed. On the banks of the river, a hippopotamus, a crocodile, various bird species, a snake, and even a few reeds and other plants are depicted. The hippopotamus and the crocodile face one another, posed in opposition or confrontation of some sort, which is reflected in other pairings of animals. On the far-right side of the central panel, two herons stand against one another, beak pressed against beak, while on the left, a jackal and a snake seem similarly hostile, as the snake lifts its neck and stretches out its tongue in a hiss. This conveys a distinctly exotic atmosphere which lacks any kind of human figure, a stark departure from the great battle mosaic which lies above it, though these pairings of hostility might echo the opposition between Alexander and Darius.

The Alexander Mosaic

Set into the floor of the exedra, wedged between the large and small peristyles, lies the Alexander mosaic. It occupies almost entire floor space, indicating that no klinai23 were meant to permanently occupy the room so as to not cover the extravagant image below. It has a thin, geometric border of alternating white and brown stripes with small rosettes inscribed in each of the four corners. A battle enfolds with a panoply of human and equine bodies all engaged in various levels of violence. The left side of the image, where most of the Macedonian army is illustrated, is heavily damaged and missing, with only the figure of Alexander the Great himself rising above the missing sections of mosaic work.24 His face is youthful and bears the mark of one who is deeply focused and engaged in battle, yet utterly calm. He has a ruddy pallor from physical exertion, and wide, distinctive eyes; however, only one eye is visible, as Alexander’s face is rendered in profile, with the rest of his body fully frontal, facing outwards and revealing a gorgon painted on his breastplate. The other two Macedonian figures which have not been obscured by damage are only partially visible: the helmeted man behind Alexander lifting his arm in preparation to fling his spear and the sliver of a man’s profile to the right of Alexander. Alexander’s horse rears in the face of the onslaught of Persians who appear as fully capable and worthy opponents. This mode of respect toward the Persians is exemplified in their leader, Darius III, who is compositionally the highest figure in the entire scene. Unlike Alexander, Darius is not serene, but deeply agitated and expresses concern at the tide of the battle which recedes from his favor. He rides high atop a chariot, yet still exhibits care for his men, reaching toward a dying Persian soldier who had been struck by Alexander’s spear. The armies are in close proximity to one another, making the overall image alive with movement and ferocity.

napoli.it/en/mosaici-2/#gallery-19.

The Question of a Single Program

Though looking at these images separately provides a deeper understanding of their individual meanings, evaluating them together in the context of the floorplan produces a more analogous experience to that of the ancient Roman viewer. They were not isolated works of art, but part of a larger construction which also included furniture and wall painting. The viewer’s experience of these mosaics would have been a conglomeration of the images and their contexts, rather than in the sterile museum environment, hung vertically and parallel to the body of the viewer. The floor mosaics would serve dual functions, both as a guide to the way of life within the home and as a mechanism to transport the viewer into imagined spaces.

First, these images would orient the guest to the mood and function of each space. While each of the smaller mosaics initially seems to exist within its own particular placement in the plan of the House of the Faun, many participate in a Dionysian theme which invokes the god’s love of earthly pleasures.25 This was a common theme for villas, places of extreme wealth which were built as a place of leisure and retreat from the chaos of urban Rome. Though the reference to Alexander and his political success at either the Battle of Issus or Gaugamela seems incongruent with other scenes of naturalistic flora, fauna, and theater masks, the ultimate message conveyed in these depictions becomes a complicated blend of political and mythological associations. These references could be parsed by the Roman viewer to varying degrees of intensity and depth, depending on their education and interests. The cornucopia elements of the threshold mosaic might set the tone for the guest’s overall visit to a home where they encounter abundant luxury from the moment they set foot inside. As the viewer dined in the autumn triclinium and observed the young Dionysius, he might recall these exact festoons of Dionysiac plenty from his initial entrance into the home. In the summer triclinium, the image of a seascape and marine animals might reference both the meal on the table as well as its origin in nature. Because of their variety, the mosaics seem to point toward a larger celebration of the Roman noble lifestyle influenced by the opulence of Hellenistic culture, rather than all partaking in one specific program and all ultimately connecting to the Alexander mosaic. This kind of incorporation of Hellenistic images is not unique to the House of the Faun — it was part of a larger influx during the second century BC of foreign luxuries.26

For the modern viewer, studying individual motifs does not reflect the original function and interpretation of mosaic floors. A more helpful approach that imitates the historical, Roman experience would be to think about the mosaics as one aspect of the larger project of the villa — as contributing to the lifestyle of a villa-owner and creating spaces of illusion and spectacle, with all the intellectual pursuits and sense of luxuria therein.

Ancient and Modern Perception

As an urban villa, with shop fronts attached to the property and only a short distance from the central forum of Pompeii, the House of the Faun departs from the traditional villa format of an isolated country estate. Thus, the second function of the mosaics becomes operative; these floor images shift the guest’s focus inward, providing a sense of extensive space removed from the commotion of the city, while also facilitating conversation. However, moving throughout the space, starting in the fauces, progressing toward the exedra, and ultimately reaching the second peristyle, the mosaics appear thematically disjointed. This variety and the lack of a unifying narrative creates a nuanced experience, in which multiple layers of meaning within the home may be gathered.

Beyond this, the guest would have experienced the mosaics as images on the floor beneath their feet which required a physical turning of the body (at bare minimum, one’s neck) downward in order to view them. This kind of spatial relationship between the viewer’s body and the mosaics is entirely different from the current museum context which they occupy. The ancient Roman observer would inevitably step on these images. Thus, the depiction of figures underfoot informed the placement and movement of the viewer’s body, as he might be prompted to turn in certain directions according to the floor beneath him, in order to better view the tiled image. A floor paved with mosaics becomes much more consuming than painted walls, as the viewer’s body is planted upon the images. Eyes may detach themselves from a work of art much more quickly, while feet physically connect with the art below them in a way that is more long-lasting and more tactile; the floor acts as a literal support for the viewer’s body.

In the same way geometric motifs can provide dividing markers where dining couches would be set, these figural mosaics require the movement of the visitor in order to activate the narrative and observe its development. Such direct and physical reality of these mosaics also contributes to the element of illusion implicit within figural floor mosaics. Objects within the mosaic scenes descend back into space, but this illusion is inevitably and necessarily shattered when the viewer places his feet atop the mosaic stones. Thus, the true experience of a Roman floor mosaic both situates the visitor in the space physically and transports him into an imaginative realm.

Conclusion

In the House of the Faun, each space acts not as a mere backdrop, but rather informs and contributes to the social and intellectual practices of its occupants. The mosaics within these spaces, though permanent, are not static; they invite movement and invoke an entirely new realm of the imagination, beyond that of physical space. The extent of this invocation varies. The mosaics might recall to the viewer some mythological story or characters, such as the symplegma, yet grounding him in the room and its relative context within the larger home. This is created both through figural representations of new spaces, but also through the physical element of walking across the floor, as one’s footsteps obscure what is floor and what is figure below. And taking all of these images in, as one moves continually throughout the space and over the course of one’s stay in the home, the mosaics both facilitate a conceptual removal from a guest’s physical existence, as well as direct them toward the intended purpose of the room. These two-fold (and seemingly dissonant) purposes illustrate the dynamism of such mosaics. The range of experiences in these spaces was wide — the mosaics could be glanced on in passing or deeply felt. They could be abstractly applied or understood in relation to their host and his specific identity. While today these floor mosaics are no longer attached to the floor, observers must both become aware of the tradition and origin which surround them and participate within it.

Notes

- Latin word for “island” literally, but often refers to a city block. ↩︎

- Though the term “villa” is used throughout the paper to describe the House of the Faun, its floorplan more closely resembles that of urban Macedonian palaces or a Roman domus. Nevertheless Zanker (1998, 142-143) asserts that it contains many elements crucial to a villa complex, including “peristyle gardens with fountains, extensive rooms with costly mosaics … and even a small bath complex.” This form of Hellenistic interior design combined with evocations of pleasure, wealth, and leisure – which were synonymous with villa life – mark this home as a particularly interesting intersection of cultures. Considering the explicit Macedonian and Eastern reference in the Alexander mosaic, as well as the potential import of many of the house’s mosaics from a Greek workshop, it is likely that the owner of the house veered on the side of adopting Greek culture and tradition. ↩︎

- Westgate 2000, 264; Westgate (2000, 263) also mentions the particular use of lead strips, an element specific to Greek mosaics, at the House of the Faun when compared to other Pompeiian homes. ↩︎

- Latin word for “extravagance”. Russell (2015, 133) describes the Roman narrative which viewed this term either positively, associated with leisure and displays of Greek art in the villa setting, or negatively, associated with moral decline and vice versa. ↩︎

- Bergmann (1995, 82) discusses the debate surrounding origins for both the Alexander mosaic masterpiece and other smaller mosaics in the house. ↩︎

- Plural form of emblema, meaning a “separate ornament … that was attached as decoration” (Merriam-Webster). ↩︎

- For further reading on the Hellenistic influences in Pompeii, see Zanker 1998, 3-7; for reading on Hellenistic style found within the House of the Faun specifically, see Zanker 1998, 39-41. ↩︎

- An architectural space, generally outside. McElmurray (2003, 2) defines this room as intended “to serve as aesthetically enhanced conversational place with seating provided for small groups.” ↩︎

- Dwyer 2001, 329-332. ↩︎

- Ibid., 338. ↩︎

- A technique of ancient mosaics which Cohen (1997, 7) describes as “[utilizing] the tiniest tesserae and [arranging] them in wormlike patterns that give this technique its name.” ↩︎

- The question might arise whether or not all the floor mosaics are contemporary of one another or if some were installed before others. However, the exact timeline of the various mosaics’ installation cannot be determined; thus, for the scope of this paper, it is helpful to consider only the experience of the Roman visitor in 79 AD, when it is certain that all the mosaics under discussion were in place, rather than the experience from an earlier time in which the home’s mosaics might have been different than what remains today. ↩︎

- Kraus 1975, 68-69. ↩︎

- Christensen 2006, 6-7. ↩︎

- Christensen 2006, 6-7. ↩︎

- Richardson 1988, 124-126. ↩︎

- Cozzolino 2022, 4. ↩︎

- Latin word for “passageway”. ↩︎

- Latin for “father of the household”. ↩︎

- Latin word for a small, private room, often referring to a bedroom. ↩︎

- Varone 2000, 90-94. ↩︎

- Latin word for “dining room”. ↩︎

- Greek word for “couches”. ↩︎

- Richardson (1988, 20) notes that the damage is likely a result of the earthquake of 62 AD. ↩︎

- Zevi 1998, 54. ↩︎

- Russell 2015, 133-135. ↩︎

Acknowledgements: To Dr. Abbe and Grace, for their steadfast guidance in this project. And to my parents, for supporting and encouraging me always.

Citation Style: AJA – American Journal of Archaeology