An Analysis of the United States WWII Memorial

by Sydney Thornton

The design and construction of the National World War II Memorial preach the idea of unity and the dominance of the United States throughout the war. The design has aided in creating public memory about the war, as well. By examining elements of the memorial, the history of the United States’ involvement, and the impact of the war, the memorial’s implications for public memory are discussed. The memorial’s narrative of unity and dominance is false, countered by the many xenophobic actions the country has witnessed, such as the use of internment camps for Japanese people. Ultimately, it is important to criticize the memorial’s design while respecting the people it honors.

World War II, public memory, memorials, architecture, history, collective memory

At the beginning of US history, elected officials argued that monuments and statues were pointless, and a person’s actions and heart would be monumental enough. President John Quincy Adams said, “Democracy has no monuments” (Savage 1). However, the United States became a very iconographic country as time passed. The National Mall in Washington, D.C., demonstrates this, as it features dozens of monuments and memorials dedicated to the people, events, and wars that built this country. The National World War II Memorial is among the largest and most symbolic. The memorial is made up of different pieces that honor the country’s heroes but also push a nationalistic agenda that continues to impact our collective and public memory.

As its name states, the memorial centers on the Second World War and how the conflict impacted the United States. World War II lasted from 1939 to 1945, with the United States joining in 1941 after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7th (National WWII Museum). On December 8, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared war on Japan, with Italy and Germany declaring war on the United States in solidarity. The war changed all Americans’ lives for numerous reasons, including the draft’s implementation in late 1942 for able men aged 18-64 (National WWII Museum). Meanwhile, women joined the workforce to support the country. These changes as well as the loss of 418,500 US military and citizens who died in the conflict, needed to be honored (National WWII Museum).

Much time and effort were spent planning the National World War II Memorial. Congress wanted to ensure it captured the spirit of the people and efforts during wartime without disturbing any existing monuments already in the National Mall. The memorial was proposed in 1987 (Biesecker 393). President Bill Clinton authorized the memorial’s construction in 1993, but challenges arose concerning the monument’s location and design (National Mall Coalition). While President Clinton approved the memorial’s construction in D.C. where many other monuments dedicated to the country’s history already stood, there were worries that the new monument would disrupt the flow between the Lincoln Memorial and the Washington Monument in the National Mall.

The Rainbow Pool was already a central and beloved feature of the National Mall. Its location was considered a prime location to include such an important piece of US history. Therefore, the WWII monument needed to incorporate the Rainbow Pool as part of the narrative. If the monument interrupted the chronology of other monuments, visitors would get a fractured understanding of history. While the design was under deliberation, location became an important factor in considering how best to present the narrative.

Once the location was determined, the design itself became the central issue. Three years after President Clinton’s authorization, a competition to design the memorial was announced, and Friedrich St. Florian’s design won. This outcome caused controversy as St. Florian’s original design was considered too “bulky” (National Mall Coalition). St. Florian attempted the design a second time after studying European war memorials, and this one received approval.

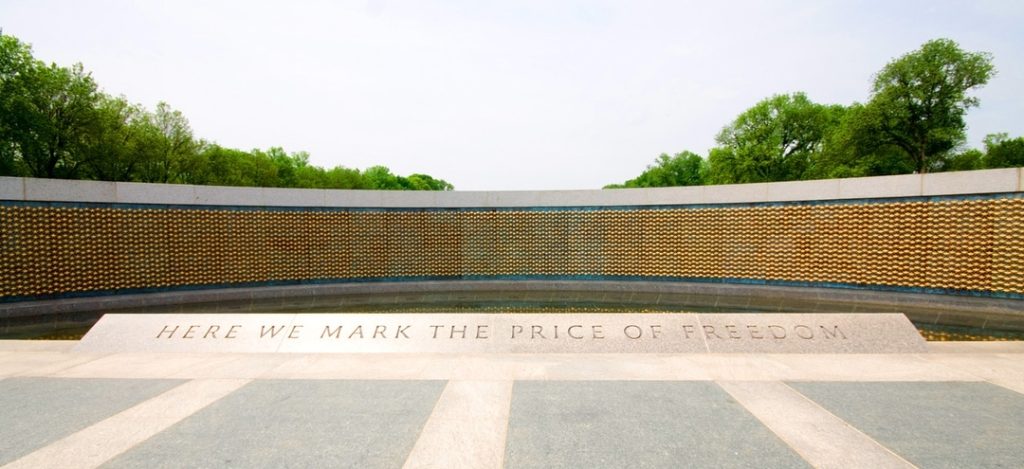

Construction on the sight began in September 2001, and the Bush Administration completed it in 2004. The whole process took over ten years to complete. Today, the memorial has many intricate pieces dedicated to those who served and the citizens who supported the country. The memorial has distinct sections: the flag poles, the plaza, the pavilions, and the freedom wall. These weave the story of each state’s role in the war, civilians’ efforts, and how the country purportedly came together to aid in the conflict.

The two flags on either side of the memorial are dedicated to the military. The base of each pole has the emblems of the branches of the US Military to respect their contributions (Martinez).

The Rainbow Pool, originally part of the Lincoln Memorial and the leading cause of concern in St. Florian’s design, was incorporated into the new plaza. The plaza contains 56 pillars representing the states and territories of the union, all linked by a bronze rope that is the nation’s bond. Each pillar also has two wreaths, one made of oak and the other wheat, representing the United States as a global arsenal and “breadbasket of the world” (Friends of the National World War II Memorial). The 24 bronze panels along the sides of the memorial depict different efforts during the war. They include those fighting in battle, farmers growing food for troops, and more.

This memorial’s primary purpose is to demonstrate how every American was part of the war effort. This purpose can be seen in many of the bronze panels, such as the panel dedicated to women’s efforts in the war (National Park Service). The panel below documents the emergence of the Rosie the Riveter figure. By highlighting women’s engagement and progress in the workforce, the monument further casts the United States’ involvement in the war in a positive light in public memory.

On either end of the plaza are the pavilions that represent each theater of the war. The Pacific Theater is honored by the pavilion to the south and the Atlantic by the pavilion to the North. Both pavilions have the same interior, with four eagles holding a laurel wreath. The floors of the pavilions have bronze World War II Victory Medals.

Across from the Rainbow Pool lies one of the most somber parts of the memorial: The Freedom Wall. The Wall marks the price of freedom with 4,048 Gold Stars, each one representing 100 American military members who died or went missing (Craven). The gold stars are a tribute to the ones people would wear if they had lost a family member in combat (Gold Star Mothers). The 13 pillars closest to the Freedom Wall are those of the 13 original colonies, states that have always been part of the fight for freedom. The rest are ordered by when they achieved statehood or joined the union.

During the war, people unified to fight and provide for their country, and the memorial echoes that. After the 50th anniversary of World War II, President Clinton signed off on the memorial’s construction to commemorate the conflict and unify the surrounding memory. However, while it honors those lost in the war and the country’s efforts, it is important to remember how this monument is used to influence public understanding of this event.

World War II harbors a lot of emotional history for numerous groups of people. This conflict changed the warfare landscape with the introduction of nuclear weapons and created a more globalized planet due to the conflict. It changed how the US government told its narrative, and the National World War II Memorial continues to tell this changed, nuanced story. One of the main themes across the memorial is the idea that the country was unified together in this war. The creation of this monument came at a time when President Bill Clinton wanted to stress that Americans needed to work together, saying in his dedication speech that the monument “will be a permanent reminder of just how much we Americans can do when we work together instead of fighting among ourselves” (Biesecker 394). President Clinton used the creation of this memorial to push an agenda of cooperation, which is admirable; however, the monument conveys messages that are not entirely true about American history or politics.

The idea of unity seen in this monument does not demonstrate the rampant racism and xenophobia experienced at the time of the war. Executive Order 9066 sent people of Japanese descent to internment camps during the war period (Shew and Kamp-Whittaker 303) out of fear that they were spies on US soil. History textbooks often exclude this piece of history, and monuments dedicated to those imprisoned are few and far between. As a result, this treatment of Japanese Americans has been forgotten in the public memory. More recently, the impact of this executive order has been addressed with historic sites across the country, such as the Manzanar National Historic Site, which recognizes this atrocity. Still, the ramifications of this executive order are still being felt today and require more proper apologies and reparations. President Joe Biden said on February 19, 2023, that Executive Order 9066 represents “one of the most shameful periods in American history” (Neukam 1). Archaeological digs are now ongoing, and sites of these internment camps are being incorporated more into public memory. In March of 2022, Amache National Historic Site became part of the park service, highlighting another site of a tragedy that resulted from Executive Order 9066 (US Department of the Interior). Every impact of the country’s involvement in the war must be acknowledged, not just the positive aspects highlighted by the National World War II Memorial. Therefore, as the nation’s history is memorialized in places like D.C., monuments dedicated to this tragedy should be incorporated into more public spaces for proper reflection, not just retained in the remote sites where camps existed.

Internationally, the United States’ involvement in the war caused mass civilian casualties. This is typical of any war, but the heavy use of bombing contributed to a death toll far higher than anything seen before. “Between 90,000 and 166,000 people died in Hiroshima, while another 60,000 to 80,000 died in Nagasaki” (Listwa) after the atomic bombs were dropped, and even more died from radiation poisoning. Dresden, Germany, too, was heavily bombed in February of 1945. Historians estimate that about 25,000-35,000 were killed in a blaze that lasted for weeks, described as nothing short of “apocalyptic” (Dawsey). It makes sense that the US government would not want to include these sorts of statistics in a public memorial dedicated to the peace they brought. Yet in leaving them out, the government erases those parts of history and refuses to acknowledge those still suffering from these events. The discourse around the use of atomic bombs has increased in recent years, but these discussions happen predominantly within academia and keep the general public from understanding the full history of these events. As a result, only positive public memory is maintained, keeping civilians unaware of the damage the country caused.

This memorial and the “unified” public memory it attempts to reinforce can be dangerous, separating people from the not-so-distant past and sweeping aside issues from long ago that remain battles we are still fighting today. Creating the idea that the United States was the harbinger of peace at the war’s end is also very dangerous. This a purposeful misuse of historical facts to try and deliver a story that the United States is the most powerful nation on the planet and should be credited with single-handedly saving the world from destruction after World War II. Both public and collective memory are impacted by the spread of misinformation here. Many people have their collective memories invalidated, like those whose families were in the internment camps. While the memorial has honorable intentions, it is still being used to justify a place in history where the country committed atrocious acts, with lasting ramifications. While the country has seen a shift with recent attempts to change public memory, citizens are using their lived experiences to negate the idea that the war was a unified effort, like the one used in public memory. people continue to fight using their collective memories to negate the public memory, This goes directly against the unity that the memorial, and the government, preach.

The National World War II Memorial is meant to memorialize and honor the country’s past conflicts. The memorial was intricately planned to symbolize different sides of World War II and commemorate the efforts of the American military and citizens. As a result, we now have a beautiful memorial where people can reflect on the conflict and remember those who participated in the fight; however, these noble intentions cannot cause us to forget the memorial’s other implications and what it does not capture. The United States has built this story that the country is the savior of democracy and that without the country’s efforts, the world would be plagued by tyrannical chaos. This is simply false and creates an aura of nationalism embedded in our public and collective memory. As people currently fight to express the harmful effects of this narrative, it is important to criticize the monument without faulting everything it honors. Analyzing events commemorated by permanent memorials provokes thought and reflection that is meant to inspire and perpetuate ongoing thought and reflection. World War II will continue to be a dark place in history, but the National World War II Memorial beautifully honors those who served. It provides a lesson to the public about how our country behaved and how we can still be critical of and respectful of these memorials. The memorial is a testimony of how something can honor important people while also leaving out the stories of marginalized people. It serves as important reminder that we must still remain critical of monuments meant to document a collective experience.

Works Cited

Biesecker, Barbara A. “Remembering World War II: The Rhetoric and Politics of National Commemoration at the Turn of the 21st Century.” Quarterly Journal of Speech, vol. 88, no. 4, 2002, pp. 393–409., doi:10.1080/00335630209384386.

Craven, Jackie. “Who Designed the National WWII Memorial?” ThoughtCo, 3 July 2019, www.thoughtco.com/friedrich-st-florian-designer-wwii-memorial-177378.

Dawsey, Jason. “Apocalypse in Dresden, February 1945: The National WWII Museum: New Orleans.” The National WWII Museum | New Orleans, 13 Feb. 2020, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/apocalypse-dresden-february-1945.

Friends of the National WWII Memorial. “Virtual Tour: WWII Memorial.” YouTube, 28 July 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KtEJJffWvT4&t=13s

“History of the Manzanar Cemetery (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 6 July 2022, https://www.nps.gov/places/history-of-the-manzanar-cemetery.htm.

Listwa, Dan. “Hiroshima and Nagasaki: The Long Term Health Effects.” K=1 Project, Columbia University in the City of New York, 9 Aug. 2012, https://k1project.columbia.edu/news/hiroshima-and-nagasaki.

Martínez, Maika. “Erasmus United States.” What to See in Washington, https://erasmusu.com/en/erasmus-washington/what-to-see/national-world-war-ii-memorial-11696.

Neukam, Stephen. “Biden: Japanese American Internment Camps ‘One of the Most Shameful Periods in American History’.” The Hill, The Hill, 19 Feb. 2023, https://thehill.com/homenews/administration/3865377-biden-japanese-american-internment-camps-one-of-the-most-shameful-periods-in-american-history/.

“President Biden Designates Amache National Historic Site as America’s Newest National Park.” U.S. Department of the Interior, 18 Mar. 2022, https://www.doi.gov/pressreleases/president-biden-designates-amache-national-historic-site-americas-newest-national-park.

Savage, Kirk. Monument Wars: Washington, D.C., the National Mall, and the Transformation of the Memorial Landscape. University of California Press, 2011.

Shackel, Paul A. “Public Memory and the Search for Power in American Historical Archaeology.” American Anthropologist, vol. 103, no. 3, 2001, pp. 655–670., doi:10.1525/aa.2001.103.3.655.

Shew, Dana Ogo, and April Elizabeth Kamp-Whittaker. “Perseverance and Prejudice: Maintaining Community in Amache, Colorado’s World War II Japanese Internment Camp.” Prisoners of War Contributions To Global Historical Archaeology, 2012, pp. 303–317., doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-4166-3_17.

Spain, Susan. “The Landscape Architect’s Guide to WASHINGTON, D.C.” World War II Memorial | The Landscape Architect’s Guide to Washington, D.C., American Society of Landscape Architects, https://www.asla.org/guide/site.aspx?id=35780.

“The Design of the National WWII Memorial.” The Design of the National WWII Memorial, Friends of the National WWII Memorial, https://www.wwiimemorialfriends.org/design.

“Our History.” American Gold Star Mothers, Inc., www.goldstarmoms.com/our-history.html.

“Research Starters: Worldwide Deaths in World War II: The National WWII Museum: New Orleans.” The National WWII Museum | New Orleans, www.nationalww2museum.org/students-teachers/student-resources/research-starters/research-starters-worldwide-deaths-world-war.

“Visiting the National World War II Memorial in Washington, DC.” Washington.org, 28 Sept. 2018, washington.org/dc-guide-to/national-world-war-ii-memorial.

“World War II: Atlantic Theater Bas-Reliefs.” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 21 May 2020, https://www.nps.gov/wwii/learn/historyculture/world-war-ii-atlantic-bas-relief.htm.

“World War II Memorial: Historical Timeline.” National Mall Coalition, www.nationalmallcoalition.org/world-war-ii-memorial-historical-timeline/.

“World War II Memorial (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, https://www.nps.gov/places/national-world-war-ii-memorial.htm.

Acknowledgments

Thank you so much to my parents for making me who I am today. Thank you to my professors for allowing me to explore such interesting topics. Lastly, thank you to The Classic Journal for the fantastic opportunity to share my writing.

Citation Style: MLA