What Did Students Value in Their Courses During Emergency Remote Instruction in Spring 2020

by Theodore Joseph Miller

In spring 2020, college courses rapidly transitioned to emergency remote instruction because of the COVID-19 pandemic. This transition was challenging for instructors and students alike, bringing unprecedented difficulties of social isolation, technological constraints, and academic uncertainty into the classroom. We collected data just weeks into this transition to better understand students’ perceptions of what benefited their remote learning in their introductory biology courses and what could be improved as emergency instruction continues. We asked two, open-ended survey questions to introductory biology courses across five instructors at four different research-intensive universities, resulting in about 460 student responses about their experiences during the transition. All responses were independently characterized through two stages of qualitative content analysis. The first aimed to capture every idea expressed, for each question, by students through inductive generation of descriptive codes. Through cycles of iterative review and revision of the codes, we developed two robust and reliable codebooks outlining students’ perceptions of the transition. Next, larger themes were developed to capture students’ experiences and perceptions. We found that classes valued different instructional practices and benefited differently from each. Our findings show that students valued knowing what to expect throughout their course, having additional instructional support and communication, and receiving opportunities that improve content accessibility and provide them with control over their own learning.

COVID-19, Higher Education, Crisis Learning, STEM, Remote Instruction, Pedagogy

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic in spring 2020 forced colleges and universities to abruptly modify instruction to ensure faculty and students’ safety. With issues of social isolation, technology and Internet barriers, and additional familial and financial responsibilities, COVID-19 has radically changed the learning environment for both students and faculty (Gillis, 2020). While traditionally accustomed with face-to-face learning formats, U.S. institutions transitioned their curricula online (Gillis, 2020). This limited the spread of the virus and provided instructors and students with needed flexibility during crisis learning. However, the transition was unprecedented, and instructors may not have had the knowledge or experience necessary to implement effective virtual engagement strategies in their new online classroom (Carlile, 2005). Further, online learning typically takes about six to nine months to plan, develop, and prepare (Cooper, 1999). Deadlines of two or three weeks were faced for planning emergency instruction, and this new learning environment lacked its normal counterpart’s social supports, library resources, and curricular engagement (Gillis, 2020). Emergency instruction differs from online learning by focusing on providing temporary and immediate access to instruction for students rather than creating a robust educational ecosystem. While academic institutions are transitioning back to in-person instruction, it is still vital that educators understand what worked and failed to work in keeping students engaged, so instructors can consider the prevalence of barriers to student learning and adjust instruction to meet students’ learning needs in both crisis and traditional settings (Swan et al., 2000).

Teaching during crisis is not novel to the COVID-19 pandemic. Disruption to learning—caused by traumatic events like political upheaval, violence, and social disasters—has been seen both historically and in case studies on some Afghanistan schools shifting education online due to violence against women seeking access to education (Davis, 2011). Emergency instruction, like this, has limitations in providing resources needed to effectively plan and teach (Gillis, 2020). The spring 2020 transition is no exception. University support failed to provide the same level of assistance in course design, course content, learning management system literacy, and multimedia knowledge as before (Prokes, 2021). Further, stressors present in the traditional academic setting are exacerbated during crisis, including new financial and employment situations, limited social support systems, and heightened anxiety (Kemp, 2004). Building an effective and equitable online learning environment for students takes time and understanding of these struggles. Attitudinal outcomes of students’ experiences from crisis learning are of interest for evaluating and improving remote instruction (Moore, 2002). Evaluation feedback on students’ interest, motivation, engagement, and overall challenges with their learning directly connects to learner success (Allen, 2004). Faculty would benefit from gathering this information to serve as potential recommendations for virtual instruction in both crisis and non-crisis settings and assess emergency instruction.

Past studies have reported on what students value in engaging lectures and virtual course structure: students in physiology courses prefer lecture styles that allow them to review material, pace their own learning, and visualize concepts through illustrations and diagrams instead of text-only lecturing (Choe et al., 2019). This aligns considerably with the guidelines for lesson planning laid out by Mayer’s Multimedia Practices. Course practices with these components in mind have been recommended to instructors redesigning their virtual courses to improve students’ learning experience (Choe et al., 2019; Greer, 2013). However, these studies address virtual course design as if students opted into virtual learning rather than being forced into it. Research is still needed to identify students’ values when experiencing emergency remote learning, like with the spring 2020 transition.

Given the strain that faculty faced in the transition—and the possibility of future instances of disruption to face-to-face instruction—it is imperative to analyze the transition from students’ perspectives. Institutional faculty are not all experts in online instruction trained in digital literacy, and instructors with limited experience implementing online learning may struggle to rapidly acquire this knowledge—with limited support—over two weeks. Uncovering emerging themes and practices that students considered effective can help mitigate this challenge and help faculty implement engaging and flexible online practices within their classroom. Therefore, we examined students’ experiences during the spring 2020 emergency remote learning transition from COVID-19, asking what students valued in their introductory biology courses. Our study aimed to understand what students perceived as benefitting their learning and what students would recommend to instructors. By analyzing data on students’ perceptions of the emergency transition, we can better understand what was valued for their learning.

Methods

Participants

Participants consisted of 492 (349 women and 143 men) undergraduate students across four universities and five classrooms in the spring of 2020. Every student enrolled in each class was invited to complete a few questions as part of a larger survey. Large classroom introductory biology courses in which the instructor reported replacing some lecture time with active learning activities were selected. Because of empty or irrelevant answers, we eliminated some responses. This led to a total of 468 viable responses for Q1 and 462 viable responses for Q2 out of 493 total students. The response rate averaged 96% across the five classes with a standard deviation of 1.4%. These responses reflected multiple backgrounds of introductory biology students across various national institutions; this representation can potentially account for the situational differences students may have encountered.

Data Collection

Students were asked two survey questions aimed at uncovering student perception of beneficial practices in their remote learning experience, benefits relating to remote learning, and advice that they would give instructors to help facilitate their learning. Five professors at four universities assigned our survey questions to their students at the end of the spring 2020 and gave students course credit or extra credit for survey completion.

We gathered response data using the prompt and survey questions listed below:

Prompt

- Your class recently moved to online-only instruction due to the COVID-19 pandemic. With that in mind, answer these two questions:

Survey questions

- Q1: “What experiences in this online biology course were beneficial to you, and why?”

- Q2: “If you could offer one piece of advice to biology instructors about how to help students learn online, what would you say?”

Qualitative Data Analysis

Our first analysis goal was developing an initial list of the ideas that students expressed. The responses for Q1 and Q2 were analyzed separately to familiarize ourselves with the data and tentatively categorize student perceptions. We independently reviewed each response and broadly recorded emerging themes. For example, students commonly suggested that they benefited from watching lectures on their own time. In this case, we documented flexibility, asynchronicity, and self-pacing as student benefits. Each response was also summarized into a few words to help identify the core benefits and recommendations experienced. Our team saw overlapping ideas between this initial list of themes and wrote descriptions for each common theme. This resulted in an initial list of “codes”: key words with specific names that correspond to descriptions or definitions. These acted as a template for subsequent review cycles. They were revised through an initial review cycle where each code was applied back into the data and feedback was gathered on the descriptions from fellow lab researchers. Edits were made to each “code” and description for the first draft of our “codebook”. This “codebook” included a list of 18 generated “codes” from Q1 and 19 “codes” from Q2.

The second goal of our analysis was to apply, refine, and finalize this preliminary codebook. A second review of the responses was conducted to ensure our descriptions captured ideas overlooked in the first review. Supporting example quotes were added to each code and additional detail and evidence were added to the code descriptions. Feedback was again gathered from lab researchers, and their revisions—adding, collapsing, and removing codes—were incorporated. We continued these review cycles over the course of two months. Eventually, the iterative review cycles led to a final set of 26 codes for Q1 and 23 codes for Q2 with robust descriptions and supportive examples. Tables 1 and 2 provide examples of common codes that emerged from the analysis of Q1 and Q2, respectively.

Table 1: Common Instructional Practices and Their Benefits for Students

Specific Practices Benefiting Students

| Code Name | Brief Description | Example Student Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Recorded lectures & other videos | Students benefited from recorded, asynchronous lectures | “I appreciated having access to the recorded lectures, since I could rewatch them if I needed clarification on a concept. […]” |

| Recurring Assignments | Students benefited from assignments that occurred regularly | “The weekly assignments help solidify my understanding” |

| Broad Mention of Resources | Students benefited from various online programs, resources, and virtual tools | “There were lots of online resources that the professor gave, as well as giving access to the biology textbook. […]” |

| Instructor Tutoring | Students benefited from tutoring/mentoring sessions run by TAs or instructors | “I also appreciated the online GSS sessions and the TA and ULAs commitment to helping us succeed in this new format.” |

| Student Collaboration | Students benefited from peer-peer collaboration opportunities from online instruction | “Activities where I got together virtually with other students were beneficial” |

Ways Students Benefited from Practices

| Code Name | Brief Description | Example Student Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Understanding/Clarification | Aided students’ understanding/clarity of course material, lectures, or other assignments. Includes asking questions answered by professors and/or having information be reinforced through practice | “The visuals and examples were really necessary in my opinion to truly grasp what is going on” |

| Self-Pacing | Practices allowed students to self-pace and/or have a better sense of control over their learning processes | “The lecture is great, and it is very beneficial to be able to go back and replay the lecture and listen to things as many times as I need.” |

| Schedule Flexibility | Allowed students to access resources, material, or any other form of general help on their own time/schedule | “The videos were given to watch at any time. This really helped with my schedule since I could watch the videos at night when my siblings and parents are asleep.” |

| Accountability | Students became more focused and on track with subject material, assignments, etc. | “The practice questions and homework were also great too- they made sure I was on top of everything.” |

| Managing Expectations | Practices gave students awareness over future expectations and provided transparency/guidance | “Trying to keep the course the same as before with the LC has helped because I know what I have to do still and not much has changed.” |

Table 2: Common Student Recommendations for Emergency Remote Instruction Offered

| Code Name | Brief Description | Example Student Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Increased Review/Resource Material Opportunities | Students recommend implementing more independent review opportunities, practice tests, videos, etc. that can help reinforce information for upcoming assessments | “They should provide more practice tests and questions with videos working out the solutions so that students can test the depths of their understanding.” |

| Improve Practical/Interactive Lecture Content | Students recommend diagrams, visual representations, and interactive components to lectures | “Make many videos and use diagrams and metaphors to help us picture what is happening.” |

| Reduced Workload | Students describe wanting teachers to reduce homework assignments, quizzes, activities, etc. | “Please stop flooding us with homework. This class is already a lot on its own.” |

| Show Empathy & Understanding | Students recommend instructors generally be more understanding and flexible | “Be considerate! Yes, it is a weird time for the professors, but we’re struggling just as much.” |

| Increased Responsiveness from Instructors | Students recommend instructors be more responsive/aware to their concerns over assignments, future expectations, class questions, etc. | “Answer emails quickly, post assignments on time, have virtual office hours, etc. Also – communicate as often and as clearly as possible!” |

The final goal of our analysis was to consensus code the entire dataset to ensure the “codebooks” were comprehensive. Once the two code sets were completed, two lab members independently coded, to consensus, three sets of 50 randomly selected responses and one set of 80 randomly selected responses. The two lab members discussed each decision together, and consensus was achieved when both parties agreed on the code(s) assigned to the data for Q1 and Q2. Every coding disagreement was noted. The codebook was revised after each session based on agreed changes. This process continued with each randomized set of 50 responses until a strong measure of inter-rater reliability was attained over the last 130 responses. After calculating a high inter-rater reliability (IRR) value, our team finished categorizing the remaining responses.

Calculating Interrater Reliability

Two members of the research team independently coded approximately 50% of the student response data for Q1 and Q2. The first three blocks of 50 responses were coded to ensure familiarity and to practice with the codes’ descriptions and examples. Afterwards, researchers coded 80 randomly selected responses to consensus. The reliability of the code assignments was compared, between the two lab members, through Cohen’s kappa value and percent agreement. While percent agreement is the traditional standard of calculating IRR, kappa incorporates chance agreement into its calculations and provides a sounder method of ensuring correct data representations (McHugh, 2012). Acceptable kappa values of 0.8-0.9 reflect strong interrater reliability as outlined by Cohen’s statistical parameters of poor, acceptable, strong, and perfect agreement ratings (McHugh, 2012). Kappa values were calculated for the third set of 50 responses and the 80 randomly selected responses. Individual IRR values were also calculated for each initial code column.

Cohen’s kappa was calculated for two independent raters. Using unweighted statistical parameters, we focused on the same level of disagreement across every code. Each code disagreement was equally considered and no one code was emphasized over another when calculating interrater reliability (McHugh, 2012). The Kappa value of 0.848 for Q1 and 0.873 for Q2 indicates strong agreement between the raters (McHugh, 2012). This value represents the reliability of the two coders applying the codebooks to this dataset.

Results

Finding 1: Students across classes differed in preference for instructional practices, and classes reported benefitting from an individual instructional practice for different reasons.

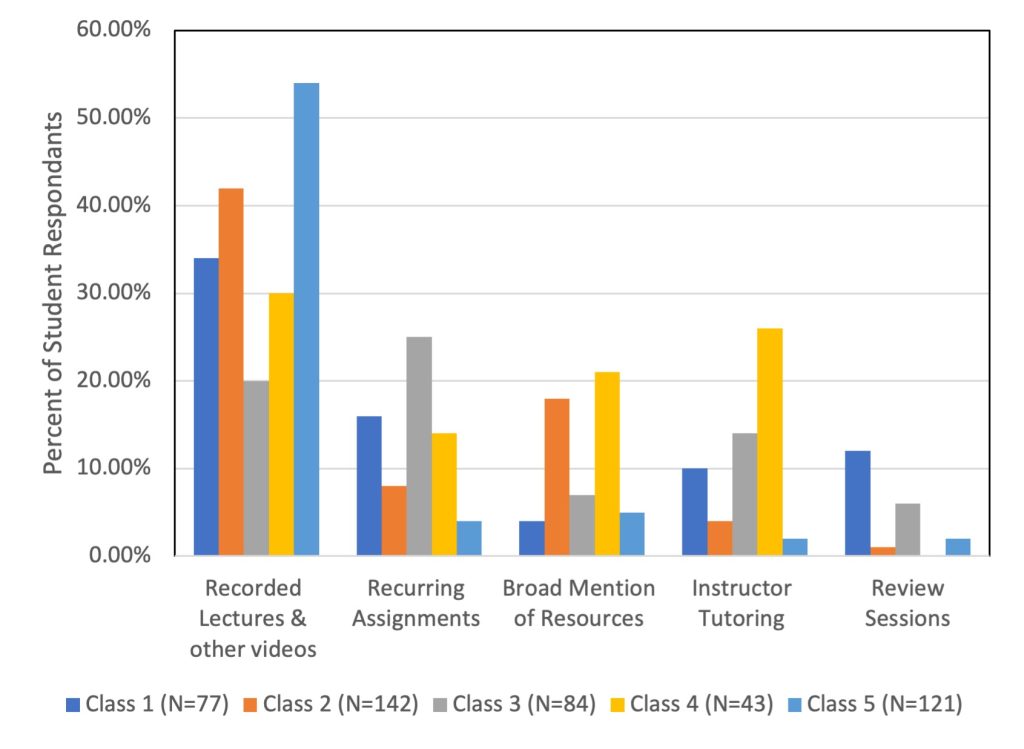

Instructors utilized many strategies and practices throughout the course of emergency remote learning, as reported by students. This included asynchronous recordings, recurring assignments, tutoring sessions, and more. However, students across the five studied classes perceived different practices as beneficial for their learning, as seen in Figure 1. Over 50% of students in Class 5, for example, reported benefits from recorded, asynchronous videos. Students in other classes, like Class 3, placed more value on recurring assignments. Further, students in some classes benefited from additional instructional practices, like review sessions in Class 1. Students most commonly benefited from asynchronous lectures, recurring assignments, online resources and learning tools, instructor tutoring, and review sessions.

Figure 1. Distribution of students’ responses across classes who benefited from a specific instructional practice in spring 2020 (gathered from Q1). Recorded lectures and videos were viewed as highly favorable from all classes. High variability is seen within and across classes, indicating that classes differed in the types of practices they valued from remote learning. Some uncommon instructional practices were excluded, attributing to x<100% for student responses from each class.

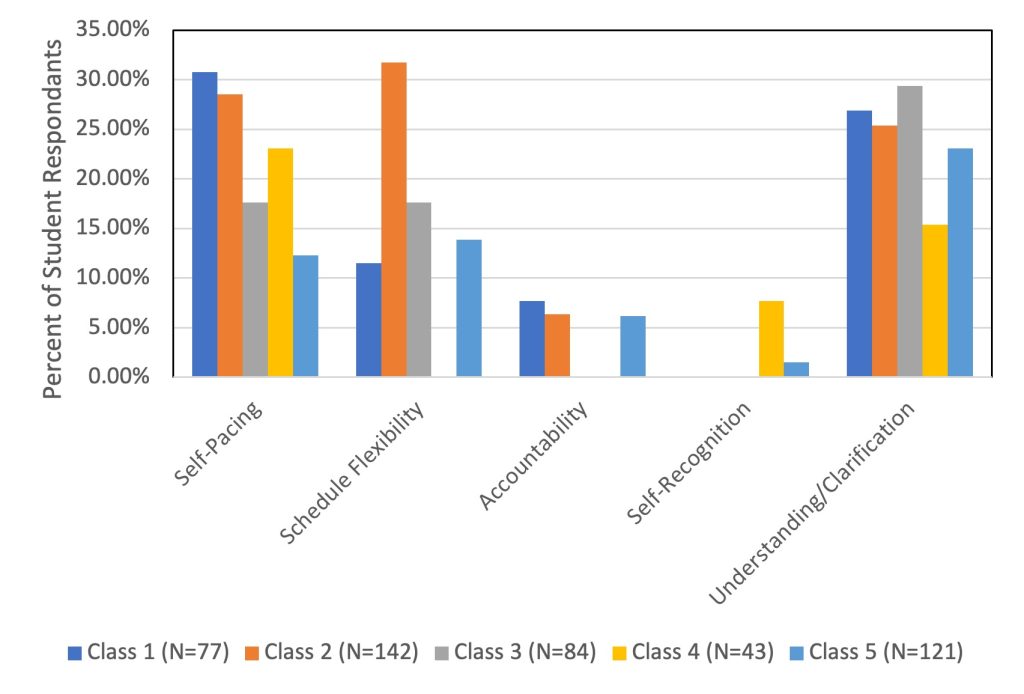

In addition, students across these courses named different ways that instructional practices benefited them. Students in Class 1 reported self-pacing and understanding/clarification as the most common benefits of recorded lectures with schedule flexibility being considerably less beneficial. Other students, like those in Class 2, equally reported these three benefits. Some classes had students that cited one singular benefit from a practice whereas other classes had students citing multiple. Further, one class may not have perceived a particular benefit from an instructional practice while another class emphasized it. We analyzed both the practices that students described as beneficial and the nature of the benefit. As seen in Figure 2, the instructional practice of “recorded lectures and videos” benefited classes in many ways: increasing students’ understanding of content, giving students’ more chances to self-pace their learning, and increasing flexibility within students’ schedules. So, classes varied or disagreed in their preferred practices and the benefits derived from them.

Figure 2. Percentage of students that cited benefitting from recorded lectures and videos AND the different ways these students benefited from this specific instructional practice. Students who benefited from recorded lectures/videos (as outlined by responses in Q1) were stratified into different groups based on how they specifically benefited from this specific practice (Q2). High variability is seen within and across classes, indicating that classes differed in the ways they benefited from remote learning practices. Some uncommon benefits arising from recorded lectures were excluded, attributing to x<100% for student responses from each class.

Finding 2: COVID-19 changed what students needed.

Students Valued Flexible Access to Course Content

Students across classes benefitted from additional control and flexibility during emergency remote instruction, and they recommended that instructors make course content more convenient and accessible (Table 3). Flexible practices helped them balance their coursework despite possible Internet issues, time constraints, and other academic and social responsibilities.

Some quotes from students included:

- “Something that helped was having recorded lectures online, so I can rewatch, pause or rewind the video […]. This was especially helpful when I did not always have WiFi”

- “I would say the ability to be more flexible in my schedule for when I decide to do a lecture is definitely a blessing in its own right […] things come up concerning friends or family and other classes plus being a waiter. I am allowed much more freedom and can incorporate much more things into my life than before.”

Students also revealed that asynchronous lectures and videos helped them identify gaps in their understanding of lecture concepts, reporting that flexibility and student-centered control over content pacing allowed them a chance to better obtain that knowledge. Further, reviewing lecture material allowed students to monitor their understanding of difficult concepts and immediately identify and address their confusion. These students said that having control over lecture pacing and dictation of speed better suited their own studying habits, allowing them to be more engaged in the material:

- “I am able to stop and rewatch lectures when I need to so I can help clear up misconceptions that I have while I study and stay focused in case I drift off.”

- “Recorded lectures also helped me because I could rewatch parts I did not understand, stop the video to take notes, pause the video to take a break and come back with more attention, and I could hear and concentrate better.”

- “I was able to replay and rewatch my professor in the recorded lectures to better understand more challenging topics for me and revisit the material as soon as possible.”

Students Valued Knowing What to Expect

Students across classes benefited from practices that helped them know what to expect and recommended instructors stay consistent in classroom organization (Table 3). Many students appreciated classroom practices that minimized confusion and managed their expectations for course progression alongside COVID-19. These quotes highlight students’ preference for course organization and high levels of instructor communication:

- “Organizing the class better, putting everything in one place is key on Canvas, its stressful trying to keep track of all of our classes online”

- “To send out weekly reminders like in the Weekly Round-Ups of what is due and what is coming up, just because things can get lost in translation when all online.”

Students—in all classes—also said regular assignments held them accountable for their schoolwork during COVID-19. This consistency (on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis) gave students a sense of stability and routine in their learning. These students below describe these points, explaining their appreciation for recurring assignments’ internal consistency and how its accountability improves students’ learning despite COVID-19 conditions:

- “[…] We even kept doing the in-class activities, discussions, and homework we would have done in-person. My instructor did a great job of adapting, and these activities kept us engaged despite being online. It made things feel normal and it wasn’t that different in my opinion”

- “I found it helpful that the professor required that students answer weekly online Learning Catalytics questions about the material we were covering at the time. I found that this held me accountable and kept me aware of class expectations instead of not caring because of COVID.”

Finally, students explained that they preferred practices that helped them prepare for summative assessments. Some students appreciated homework modules and worksheets that aligned with material seen on future exams, recommending that assignments directly address exam-like questions. Students below emphasized the value of consistency for exam preparedness:

- “Doing the worksheets every week really prepared me for the exams. The questions were super similar, and I feel like doing the homework made me more comfortable with the quizzes and the new online setting.”

- “I had no idea what the new format of exams would like and that it wouldn’t test the same things expected of me before. Maybe alter assignments to us that reflect what the exam will look like and whether it will be just memorization or more critical thinking?”

Students Valued Instructor Support

Students across classes benefited from practices that promoted their overall wellbeing, recommending that instructors be lenient and understanding of students’ difficulties during emergency remote teaching (Table 3). There were various reasons for why students recommended for additional leniency and understanding, but most of them dealt with adverse effects from the pandemic on their personal lives. Students here show specific reasonings for wanting additional instructor support from their classes:

- “Be considerate! Yes, it is a weird time for the professors, but we’re struggling just as much, and I have so many more assignments to complete.”

- “I am overwhelmed with how COVID is changing my work schedule and now I have to find day-care support along with this class. I just would have appreciated a little more understanding and compassion from this class, but I did not get any.”

Other students reported that they benefited from flexible course practices like their instructors modifying course requirements, grading scales, and assignment deadlines. Professors changed the way they evaluated students because of new learning environment challenges. From receiving extra opportunities for course credit and extending exam times, some students responded that their instructors’ awareness and ability to act on their struggles benefited their learning:

- “My instructor made assignments completion based and exams untimed so students were less stressed about getting good grades and I could focus on and enjoy learning instead of worrying about being perfect.”

- “Having the chance to receive extra credit really made such a difference for my grade and helped a lot because I could not attend some lectures because of my job and my mom when she got COVID.”

Table 3: Student-Derived Values from Initial Qualitative Codes

| Students’ Values | Initial Descriptive Codes |

|---|---|

| Flexible Access to Course Content | · Recorded Lectures & Other Videos · Broad Mention of Resources · Self-Pacing · Schedule Flexibility · Assignment Timing/Flexibility · Increased Review/Resource Material Opportunities · Additional Synchronous Instructor/Group Review Sessions · Shorter Lecture Videos |

| Knowing What to Expect | · Course Consistency · Recurring Assignments · Organization of Materials · Managing Expectations · Exam/Quiz Preparation · Instructor Communication |

| Instructor Support | · Show empathy & Understanding · Modify grading & Reporting Practices · Extended Exam Timing · More Office Hours · Simplify Concepts · Reduced Workload |

Discussion

Our results provide an important first look into what introductory biology students valued during the transition to emergency remote instruction in Spring 2020, suggesting various ways in which students perceived the effectiveness, or lack thereof, of emergency instruction. The student perceptions summarized in this paper can suggest some guidelines for instructors to consider when deciding how they structure their classes. We also encourage instructors to gather their own students’ perceptions regularly.

Key Concept #1: Increase Opportunity for Flexible Access to Course Content

Learning during a global pandemic provided many unique challenges for students. Many experienced technology problems like accessing lectures; others felt overwhelmed with managing school and their other obligations (Prokes, 2021). One student, for example, mentioned that living in a rural community made it extremely difficult to have stable access to course content due to Internet problems. The importance of effective and continuous communication and accessibility reported by students relates to their increased questioning of the value of higher education. The realities of COVID-19 have brought higher education into question, and students have reconsidered attending given the financial burden and new uncertainties (Baggaley, 2020). With the increased rate of U.S. college students taking gap years and dropping out during COVID, communication, accessibility, and clarity become even more vital for faculty to ensure retention (Gillis, 2020). Students’ suggestions from our data reiterate this need for instruction to work with their schedules, and research shows that student-centered pacing increases the social, emotional, and self-regulatory needs for student learning (Trujillo, 2014). Student engagement and interest increase when instructors provide students with additional resources, independence, and flexibility, like allowing for students to design their own projects and lead their own discussions before specific deadlines (Baggeley, 2020; Gillis, 2020). Our data implies that flexibility in content and pacing may be effective at keeping students engaged not only within the classroom, but also with their interest in higher education overall. Therefore, faculty should consider designing virtual course policies that acknowledge students’ difficulties related to academic barriers and seek to optimize retention by providing flexible, student-led learning activities.

Key Concept #2: Monitor and Continuously Enhance Clarity of Course Expectations

A second fundamental value students held was “Knowing What to Expect.” Students and instructors both quickly transitioned into a virtual classroom setting, and our data suggests that students knew little of what would be expected of them (Gillis, 2020). Across all classes, students benefited from and recommended practices that established consistency within the course, prepared them for examinations, and managed their expectations for how the course would progress. Clear standards for course progression have been shown as vital for maximizing learning, as students can participate more effectively when they have a clearer understanding of expectations (Swan, 2000). Our data suggests a similar idea: by keeping “tried and true” instructional practices and behaviors from in-person, students found that organized assignments, deadlines, and course materials enhanced their learning. Students that can consistently identify classroom expectations and receive consistent reinforcement for their learning behaviors show increased classroom retention (Swan, 2000). Instructors moving forward in either virtual or face-to-face teaching should consider maintaining practices that students are familiar with or ensure that students are comfortable with and aware of new changes in course structure.

Key Concept #3: Prioritize Social and Academic Support Systems

Finally, our findings suggest that students valued “Instructor Support”. Responses showed that academic stress has been exacerbated by COVID-19, which has hurt students’ ability to concentrate and maintain motivation. Increased anxiety and diminished wellbeing primed students to ask for instructors to “remember that they are human” and need both social and academic support to succeed.

These recommendations suggest instructional immediacy as a classroom priority during crisis teaching. Characterized by behaviors that establish positive social connections between instructors and students, instructional immediacy has been shown to improve motivation, engagement, and learning outcomes (Seidel, 2015). Instructor talk is one way in which instructors can achieve immediacy and help students receive the academic and social support they need (Seidel, 2015). By sharing personal experiences, revealing personal information, and respecting students’ difficulties, instructors can build students’ social connections to the class and use non-content language to guide student-centered learning goals (Seidel, 2015). Regulating stress is important for undergraduate students to avoid burnout and academic shortcomings, and external social pressures from COVID-19 have made students more uncomfortable with and resistant to learning (Allen, 2002; Gillis, 2020). Our data suggests that faculty should prioritize both content and non-content related behaviors that personalize the classroom and increase instructor immediacy to improve students’ social connection and learning comfort. Future research can be directed at evaluating the effectiveness of immediacy behaviors on students’ self-efficacy in times of crisis and how non-content related speech may be used to address students’ concerns of their learning.

Implications and Conclusions

COVID-19 Instruction and Beyond

Equitable, flexible, and accessible course policies need to be applied by faculty in all learning contexts—not just emergent/remote environments (Prokes, 2021). Despite being asked about specific benefits pertaining to their emergent learning environment, some students responded broadly about valuing instructional practices that did not directly relate to the alternative instruction resulting from COVID-19. A few students mentioned feeling socially isolated in a large classroom setting before the pandemic and that remote learning exacerbated this feeling. Other students recommended having additional review sessions for exam preparation because they wished for more opportunities to go over material and learn about exam expectations throughout the entire course, not just during the pandemic. These comments suggest that the transition intensified problems that were already impacting learning before the pandemic. Concerns of course material accessibility, academic instructor support, and limited knowledge of future expectations were shown by students to be nonexclusive issues pertaining to spring 2020 instruction. By considering the common ways in which students benefited from remote learning, faculty could better adjust their teaching practices to address student concerns in all cases of instruction—not just in cases of emergent learning.

Application of Instructional Practices Can Target Unique Classroom Learning Goals

Our data also suggests that instructors apply remote instructional practices differently. Classes reported benefiting from the instructional practice of “recorded lectures and videos” in various ways as seen in Figure 2. Classes perceived many benefits from this given practice, but they differed in how they benefited from recorded videos. The variability of how classes benefited from instructional practices could have many possible explanations, including differences in institutions, course design, and individual experiences. Instructors from each class might also have had different learning objectives for students that they tried to explicitly target with certain practices, like trying to assist students’ understanding of content and critical thinking skills (Gillis, 2020). One instructor, therefore, might have focused on structuring a practice to help students prepare for exams while another might have emphasized real-world connections.

Faculty’s strategies for how they select and use tools, like using Zoom as an asynchronous video tool within their class, matter and can support their learning goals (Gillis, 2020; Head, 2002). However, students’ learning needs have changed because of the pandemic. Instructors should therefore monitor student experiences in their classes and be willing to adjust practices to help students “Know What to Expect” and provide students with additional “Instructor Support” and “Flexible Access to Content” in all learning contexts, not just in a crisis.

Table 4: Summary of Student-Based Educational Recommendations

| Student-Centered Themes | List of Recommended Guidelines for Instructors |

|---|---|

| Increase Opportunity to Flexible Access of Course Content | Extension of virtual modalities for lectures & other academic activities (e.g., synchronous Zoom options, posted recorded lectures, hybrid formats) Active implementation of supportive virtual and financially feasible course materials to reinforce retention Implement additional opportunities for review sessions, especially those than involve peer-peer active group collaboration and social communication Create learning materials that promote multiple learning styles (e.g., auditory – lectures, visual – graphical representations, kinesthetic and experiential, etc. |

| Monitor and Continuously Enhance Course Expectations | Ensure optimal alignment of syllabus expectations throughout course with minimal changes Organize materials in as few domains as possible for student clarity Highlight the cognitive skills and question types expected for students to master for exam/quiz material Provide outlines of weekly responsibilities and expectations for students |

| Prioritize Social and Academic Support | Provide occasional non-content based, supportive instructor language Periodic “Check-Ins” to elicit student difficulties and concerns Utilize “check-ins” to adjust instructional behaviors to students’ needs Place considerable time when planning curriculum structure around students’ newfound social, financial, and institutional challenges from COVID Emphasize one-on-one instructor sessions or office hours to discuss students’ academic AND social/non-academic concerns |

Limitations / Future Directions

One main limitation of our study is the qualitative coding process. While we had high interrater reliability for Q1 and Q2 student response data, each evaluator might have perceived students’ benefits and recommendations differently. Further, the interpretation and coding assignment for student responses’ might have led us to miss emerging themes. As we had about 490 responses to each question, the data was summarized into brief statements to help us make sense of students’ perceptions. However, this process might have allowed us to miss important language regarding the intensity of how students felt.

This study also collected from four, research-based universities which are unlikely to reflect the experiences of all students and possibly those of students from marginalized and underserved backgrounds. While we expect our study to encompass the attitudes and perceptions of students about the emergency learning process, the social and academic barriers related to COVID-19 cannot be reasonably generalized from our data and limited demographic knowledge of participants. The reason for this is due to our relatively uniform selection of similar universities and institution types. Our study may fail to capture the prevalence of other COVID-19 related academic disparities and barriers from non-research-intensive colleges, and this is likely given past research that shows research-intensive, liberal arts, and community colleges have different student population makeups of race, age, and gender. A more rigorous investigation of our study is therefore warranted into different institutions and diverse student populations (Gillis, 2020; Prokes 2021).

Some students cited that they have increased familial responsibilities and financial obligations. These few instances suggest that students may perceive the efficacy of remote learning differently. However, a diverse sampling of students and gathering data on students’ perceptions of in-person instruction could control for this.

Emergency learning’s issues impacted all students, not just those within the sciences. The transition may be better understood with additional investigations into non-STEM major classes instead of students solely from introductory biology. This can provide a larger scope into the values of all students during the transition and not ones that may have been exclusive to the sciences. By extending the range into varying institution types and fields, future research on this transition can address the important limitations holding students back and ensure instructors implement meaningful techniques that are tailored to the needs of their class.

References

Allen, M., Bourhis, J., Mabry, E., Emmers-Sommer, T., Titsworth, S., Burrel, N., et al. (2002). Comparing student satisfaction of distance education to traditional classrooms in higher education: a meta-analysis. American Journal of Distance Education, 16, 83-97

Baggaley, J. (2020). Educational distancing. Distance Education, 41(4), 582–588. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2020.1821609

Carlile, O., and Jordan, A. (2005) It works in practice but will it work in theory? The theoretical underpinnings of pedagogy. In: Moore S, O’Neill G and McMullin B (eds.) Emerging Issues in the Practice of University Learning and Teaching. Dublin: AISHE, 11–26.

Choe, R. C., Scuric, Z., Eshkol, E., Cruser, S., Arndt, A., Cox, R., Toma, S. P., Shapiro, C., Levis-Fitzgerald, M., Barnes, G., and Crosbie, R. H. (2019). Student satisfaction and learning outcomes in asynchronous online lecture videos. Cbe—Life Sciences Education, 18(4), ar55. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.18-08-0171

Cooper, L. (1999) Anatomy of an on-line course. Technological Horizons in Education, 26(7), 49–51.

Davies, L. and Bentrovato, B. (2011) “Understanding education’s role in fragility; Synthesis of four situational analyses of education and fragility: Afghanistan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Cambodia, Liberia,” International Institute for Educational Planning, 7-9

Greer, D. L., Crutchfield, S. A., and Woods, K. L. (2013). Cognitive theory of multimedia learning, instructional design principles, and students with learning disabilities in computer-based and online learning environments. Journal of Education, 193(2), 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002205741319300205

Gillis, A., and Krull, L. M. (2020). COVID-19 remote learning transition in spring 2020: Class structures, student perceptions, and inequality in college courses. Teaching Sociology, 48(4), 283–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092055X20954263

Head, T., Lockee, B., and Oliver, K. (2002). “Method, media, and mode: Clarifying the discussion of distance education effectiveness.” Quarterly Review of Distance Education 3, 61–68.

Kemp, N., and Grieve, R. (2014). Face-to-face or face-to-screen? Undergraduates’ opinions and test performance in classroom vs. online learning. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1278. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01278

McHugh, M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 276–282. https://doi.org/10.11613/bm.2012.031

Moore, M., Lockee, B. and Burton, J. (2002). Measuring success: Evaluation strategies for distance education. Educause Quarterly, 25(1), 20-26.

Owens, J., Hardcastel, L., and Richardson, B. (2009). Learning from a distance: The experience of remote students. Journal of Distance Education, 23(3), 57–74.

Prokes, C., and Housel, J. (2021). Community college student perceptions of remote learning shifts due to COVID-19. TechTrends. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-021-00587-8

Seidel, S. B., Reggi, A. L., Schinske, J. N., Burrus, L. W., and Tanner, K. D. (2015). Beyond the biology: A systematic investigation of noncontent instructor talk in an introductory biology course. Cbe—Life Sciences Education, 14(4), ar43. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.15-03-0049

Swan, K., Shea, P., Fredericksen, E., Pickett, A., Pelz, W., and Maher, G. (2000). Building knowledge building communities: Consistency, contact and communication in the virtual classroom. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 23(4), 359–383. https://doi.org/10.2190/W4G6-HY52-57P1-PPNE

Trujillo, G., and Tanner, K. D. (2014). Considering the role of affect in learning: Monitoring students’ self-efficacy, sense of belonging, and science identity. Cbe—Life Sciences Education, 13(1), 6–15. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.13-12-0241

Acknowledgements

Foremost, I would like to express my immense gratitude and appreciation for thesis advisor and mentor, Dr. Tessa Andrews. Without her continuous support, patience, and guidance throughout my undergraduate research work and thesis presentation, I never would have discovered my immense passion for higher education reform and improvement. Further, Dr. Andrews and others, including Dr. Katie Green, Sandhya Krishnan, and Alex Waugh, were influential in helping qualify and refine my interview coding process. Their rigorous review of my work and assistance with coding set the entire framework for my study. Most importantly, the mentorship I gained from these individuals ultimately culminated in my acceptance to medical school at Penn State College of Medicine. Their desire to see me succeed has meant more to me than words can possibly describe.

Data was collected from four universities across a larger project initiated through the Andrews Lab – DeLTA and Developing Knowledge Projects. I would like to thank every student and instructor who participated in these individual’s projects and consented to data release for my thesis project.

I would also like to thank my dear colleagues, Rishika Pandey, Blake Ventura, Nicholas McGlynn, and Mary Campbell for providing me with an unwavering support system throughout my college years.

My final dedication goes to someone who truly made my final undergraduate year special, Cody Reynolds. You inspired me when I was lost, supported me when I fell, and comforted me when I lost sight of my future. I could not imagine meeting a more kind, thoughtful, and intelligent person, and I am grateful every day for having had you be a part of my life. Thank you.

Citation Style: APA