Profits Over Patients:

Untangling the Diabetes Drug Pricing System

by Abby Young, Pharmacy

Diabetes affects millions worldwide and has only become a manageable condition in the past century due to the development of injectable insulin. However, diabetics in the United States face a growing crisis as the cost of this life-saving medication continues to rise. This paper examines the factors contributing to the inflated price of insulin in the U.S. compared to other countries, with a focus on the role of pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) and a pricing system that prioritizes profits over patients. As a result, many diabetics are forced to ration their medication, leading to severe physical and financial consequences that impact their overall health and future. Public outrage and legislative efforts at all levels of the government have led to many suggestions for change to the system. Proposed solutions include government-imposed price caps and nonprofit pharmaceutical companies that operate outside traditional market competition. Addressing this crisis requires a balance between the economic interests of drug manufacturers and the ethical responsibility to ensure universal access to insulin. This paper highlights the urgent need for change to the way that the United States prices its pharmaceuticals.

diabetes, insulin, drug pricing system, pharmacy benefit managers, patient accessibility

Imagine struggling to afford insulin, while someone just across an international border pays 10 times less for the exact same medication. This is the reality for many diabetics in America, who face drug prices much higher than those in other countries. For example, Senator Bernie Sanders pointed out that an American might pay $969 for a medication that costs a Canadian $155 and a German $59 (Why Is Novo Nordisk, 2024). This is the case for US patients buying Ozempic, which helps to manage their glucose levels and curb diabetes related obesity. Unfortunately for American patients, this pricing disparity is not unique to Ozempic—in the US, many medications cost significantly more than they do in other developed countries.

Currently, Congress is cracking down on drug manufacturers, especially those producing medications for diabetes patients. Novo Nordisk, the company that makes Ozempic, is under fire for charging high prices in the United States. A Yale study found that to manufacture a one month’s supply of Ozempic, it only costs the company between $1 and $4, yet they charge nearly $1,000 for the same amount (Barber et al., 2024). When asked why this is the case in his hearing, the Novo Nordisk CEO shifted the blame away from his company and onto America’s convoluted drug pricing system (Why Is Novo Nordisk, 2024).

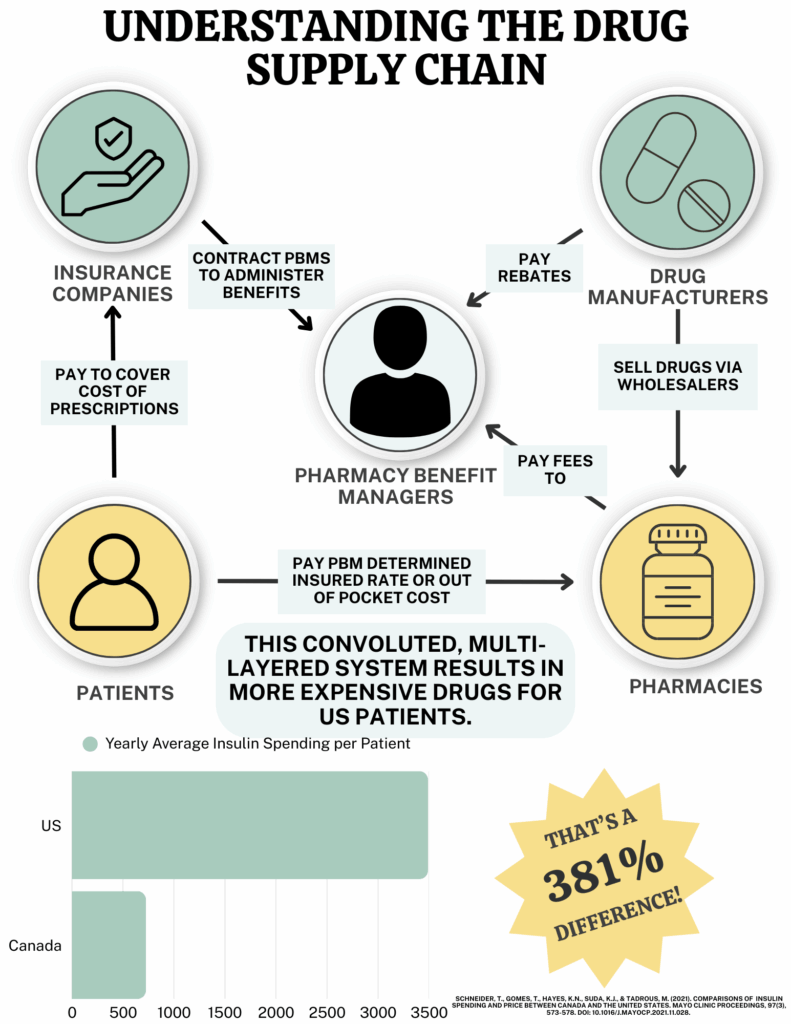

The United States has a very complex, multilayered system for determining drug prices, making it difficult to implement changes. The basic flow of the drug from production to patient works like this: pharmaceutical companies sell their drugs to wholesalers, who then sell them to the pharmacies or hospitals (Kang et al., 2020). However, pharmaceutical companies in the US are free to set their prices as high as they’d like, which means that they are often too costly for patients to pay for out of pocket (Kang et al., 2020). Thus, insurance companies help patients pay for their prescriptions. Because the initial price set by the drug company and the price with insurance can be wildly different, there is often a middleman between the manufacturers and the insurance companies: the pharmacy benefit manager (Kang et al., 2020).

Perhaps the most opaque players in the whole system are the pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), such as Optum Rx, Express Scripts, and CVS Caremark (Kang et al., 2020). In general, a PBM’s job is to save patients money by acting as the intermediaries in drug cost negotiations, going between the manufacturers and the insurance companies (Robert Smalley, personal communication, October 16, 2024). They have a significant influence on which drugs insurance companies will cover, and they leverage this power to negotiate lower prices from manufacturers. PBMs claim that they are acting in the patients’ best interests, but this may not be the case. Pharmaceutical companies often pay PBMs rebates or offer other incentives to keep their drugs priced close to their set price, and all negotiations are kept secret. With three PBMs controlling over 80% of the market, it’s unclear if any savings actually reach the patients (Kang et al., 2020).

Figure 1. Understanding the drug supply chain.

Diabetes drugs, especially insulin, are particularly susceptible to high prices today. This wasn’t always the case. In 1923, the team that originally discovered insulin sold the patent for $3, believing the drug belonged to the world (Fralick & Kesselheim, 2019). Even for that time, this price was extremely low as patents could sell for nearly $50,000. However, in the past two decades, insulin prices have skyrocketed in the US, mostly due to our pricing system. Spending on insulin in the United States increased from $2.6 billion in 2002 to $15.4 billion in 2012 (Schneider et al., 2021). In 2018, Americans spent a total of $28 billion on insulin, while Canadians spent $484 million. After factoring in insurance, the average insulin user in the US spends $3,490 annually, compared to only $725 in Canada, a 381% difference (Schneider et al., 2021).

Even after insurance, insulin prices can still be a financial burden, and this can be a scary prospect for diabetic young adults who have to learn to navigate the healthcare system to acquire their own insulin. My younger sister Amelia Young is an 18-year-old Type 1 diabetic who is currently on our parents’ insurance. This eases her worry for now, but the knowledge that she will one day need to purchase her own medications dictated her choice for her college major. “I really wanted to go to cosmetology school, but because I am diabetic, I needed a job with good medical insurance,” Young said when asked if she had ever considered how she would get insulin after college (personal communication, October 31, 2024). “I also needed something with more secure pay than a commission-based job just in case I ever do have to pay for insulin out of pocket” (Amelia Young, personal communication, October 31, 2024). It’s a disheartening reality that teenagers have to base their futures around the prices of their necessary medications.

Diabetics across the country face the same struggle to afford their insulin as Young fears she one day will, and the inaccessibility of medications can lead to a decline in mental and physical health. An analysis of over 45,000 diabetes-related tweets found that nearly a fifth were related to insulin pricing, with Twitter users expressing sadness, fear, and anger about the cost of their drugs (Ahne et al., 2020). Studies have found that those experiencing mental distress about their diabetes are more likely to have higher blood sugar levels and develop diabetes related comorbidities (Ahne et al., 2020). Additionally, a public health survey found that unaffordability of drugs led 29% of respondents to skip filling a prescription and 23% to skip doses to extend their medication supply (Parker-Lue et al., 2015). With an essential drug like insulin, lowering or skipping a dose could prove to be fatal.

This struggle to afford prescriptions and make medicines last longer is unique to the United States when compared to other developed countries, largely due to different pricing systems. Countries like Japan and Canada don’t rely on market forces to price their drugs like the US does. Instead, they use a combination of international reference pricing, which considers the price of the drug worldwide, and therapeutic referencing, which sets the drug’s price around the same as similar medications (Kang et al., 2020). Additionally, other countries’ governments have implemented price caps on drugs, whereas the United States has not, allowing manufacturers to set their initial prices as high as they wish (Kang et al., 2020). The differences in pricing systems result in US drug prices being, on average, 220 to 310% higher than those in the rest of the world (Kang et al., 2020).

These pricing differences have led to significant frustrations, prompting a series of lawsuits against various players in the drug pricing system. Robert Smalley, an attorney from Catoosa County, Georgia, is currently litigating against pharmacy benefit managers and pharmaceutical companies. Smalley believes the root of this pricing issue lies in the relationship between PBMs and manufacturers. He states, “The pharmacy benefit managers have the power to exclude a drug [from insurance coverage] to incentivize manufacturers to lower their prices. Instead, [PBMs] have continued to list the high prices set by the manufacturers . . . which benefits them because they get to keep a portion of the profits from sales of the drug” (Robert Smalley, personal communication, October 16, 2024).

Another issue, Smalley says, is that only three companies have complete control of the insulin market (personal communication, October 16, 2024). Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi are the manufacturers that set the initial price of their insulin (Robert Smalley, personal communication, October 16, 2024). When one company increases their prices, the others follow suit. These companies also maintain market dominance by evergreening their patents—making minor changes to their drug formulations or injection devices to gain up to 20 years of market exclusivity with each new patent (Robert Smalley, personal communication, October 16, 2024). The practice of evergreening prevents generic companies from entering the insulin market.

Smalley hopes that by targeting these pharmaceutical companies, he and other attorneys will be able to recover money for diabetics across Georgia who have paid “false prices based on misinformation provided by PBMs and manufacturers” (personal communication, October 16, 2024). The attorneys are also seeking punitive damages, hoping these monetary repercussions will encourage greater transparency on drug pricing deals. Smalley’s litigation and many others like his across the country are joined by a larger case being brought about by the Federal Trade Commission against PBMs for “rigging pharmaceutical supply chain competition in their favor,” resulting in inflated insulin prices (US Federal Trade Commission, 2024). These litigations mark the beginning of what will likely be a long journey for American patients to recover money lost to inflated drug prices. However, as mentioned earlier, because three large companies dominate the diabetes drug market, it will be difficult for small cases to effect significant changes to the US drug market.

Other, more large-scale solutions are being considered, such as changing the pricing system, passing laws that would lower drug costs, or even opening new pharmaceutical companies that are nonprofits. One major proposition is for the United States to use international reference pricing, which would align medication prices more closely with the lower ones paid by Europeans and Canadians (Kang et al., 2020). Another approach that is being considered is a “Netflix model”, which would allow patients to pay a flat rate each month for unlimited access to medications (Kang et al., 2020). Multiple acts have been proposed in the Senate, including the Emergency Access to Insulin Act, but no laws have yet passed through Congress (H.R.3134, 2023). As a result, it could be years before patients see price reductions from new legislation.

A third approach to changing the US pricing system focuses on altering the manufacturing system rather than the legal framework. One challenge in changing drug pricing is that pharmaceutical companies are for-profit entities, and it could be considered unfair to hold them to regulations that might reduce their profits, especially since other companies aren’t subjected to these same standards (Parker-Lue et al., 2015). A potential solution is the creation of a nonprofit drug manufacturers to produce essential drugs at low prices with limited competition. This concept is currently being developed under the name Civica. Civica produces quality generic drugs, including insulin, and sells them based on their manufacturing cost (Civica Rx, 2025). The company prioritizes making drugs that hospitals use the most often or pharmacies face shortages of to supply medications that are the most in need (Civica Rx, 2025). Since Civica supplies medicines to hospitals and pharmacies, they do not have competition for the market and thus aren’t priced out by for-profit companies. In order to prevent competition between other future nonprofit pharmaceutical companies, each one could establish their own niches to provide access to even more drugs.

Another company that is trying to offer more affordable prescription drugs is Mark Cuban’s CostPlus Drugs. CostPlus allows a user to search their medication to see if the site offers it, have their doctor send their prescription to CostPlus’ pharmacy partner, and then the medication will be shipped to the patient (Mark Cuban CostPlus Drug Company, 2025). On the company’s website, an infographic shows users exactly how the drugs they receive from CostPlus are priced: manufacturing cost + a 15% markup + pharmacy labor + shipping, which they claim is saving patients nearly $10,000 on certain medications (Mark Cuban CostPlus Drug Company, 2025). However, CostPlus currently does not offer a cheaper version of insulin, likely due to patent evergreening. The company is currently constructing a manufacturing facility, where they plan to start producing their own drugs in addition to offering patients cheaper generics (Mark Cuban CostPlus Drug Company, 2025). Hopefully, CostPlus will evolve into a drug manufacturer willing to sell insulin at a lower rate than the 3 companies currently producing it.

While there are many solutions to the problem, when asked what he thinks would help the pricing problem, attorney Robert Smalley said, “Insulin pricing caps set by the government” (personal communication, October 16, 2024). He noted that Medicare prescription drug plans have capped the price at $35 dollars a month, but this needs to be expanded to cover all insulin, Smalley believes (personal communication, October 16, 2024). Amelia Young agrees, stating that a month’s worth of insulin should not cost more than $50 (personal communication, October 31, 2024). While there is no one right solution to this drug pricing problem in the United States, something must be done to balance the economics of drug manufacture with the ethics of keeping lifesaving medications accessible to patients. 100 years ago, it was diabetics’ health that was of the utmost importance to insulin’s inventors when they sold their patent, and now the United States should shift their focus back to the patients over the profits.

References

Ahne, A., Orchard, F., Tannier, X., Perchoux, C., Balkau, B., Pagoto, S., Harding, J.L., Czernichow, T., & Fagherazzi, G. (2020). Insulin pricing and other major diabetes-related concerns in the USA: a study of 46,407 tweets between 2017 and 2019. BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care, 2020(8), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjdrc-2020-001190.

Barber, M.J., Gotham, D., Bygrave, H., & Cepuch, C. (2024). Estimated Sustainable Cost-Based Prices for Diabetes Medicines. JAMA Network Open, 7(3), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.3474.

Civica Rx. (2025). About. https://civicarx.org.

Emergency Access to Insulin Act of 2023, H.R.3134, 118th Cong. (2023). https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/3134.

Fralick, M. & Kesselheim, A.S. (2019). The U.S. Insulin Crisis—Rationing a Lifesaving Medication Discovered in the 1920s. The New England Journal of Medicine, 381(19), 1793-1795. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1909402.

Kang, S., Bai, G., DiStefano, M.J., Socal, M.P., Yehia, F., & Anderson, G.F. (2020). Comparative Approaches to Drug Pricing. Annual Review of Public Health, 2020(41), 499-512. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040119-094305.

Mark Cuban CostPlus Drug Company. (2025). Our Mission. https://www.costplusdrugs.com/mission/.

Liljenquist, D., Bai, G., & Anderson, G.F. (2018). Addressing Generic-Drug Market Failures—The Case for Establishing a Nonprofit Manufacturer. The New England Journal of Medicine, 378(20), 1857-1859. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1800861.

Parker-Lue, S., Santoro, M., & Koski, G. (2015). The Ethics and Economics of Pharmaceutical Pricing. Annual Review of Toxicology and Pharmacology, 2015(55), 191-206. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010814-124649.

Schneider, T., Gomes, T., Hayes, K.N., Suda, K.J., & Tadrous, M. (2021). Comparisons of Insulin Spending and Price Between Canada and the United States. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 97(3), 573-578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.11.028.

U.S. Federal Trade Commission. (2024, September 20). FTC Sues Prescription Drug Middlemen for Artificially Inflating Insulin Drug Prices [Press Release]. https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2024/09/ftc-sues-prescription-drug-middlemen-artificially-inflating-insulin-drug-prices.

Why Is Novo Nordisk Charging Americans with Diabetes and Obesity Outrageously High Prices for Ozempic and Wegovy?, 118th Cong. 1-21(2024) (testimony of Lars Fruergaard Jørgensen).

Acknowledgements: Thank you to Dr. Holly Gallagher for her help on this paper, and to Robert Smalley and Amelia Young for their interviews.

Citation Style: APA