Soviet and Vietnamese Early Communist Propaganda:

The Role of Culture and History on the Battlefield of Legitimacy

by Jordyn Faucette, Classics, English, Philosophy, and Political Science

This project seeks to question the role of propaganda in establishing political legitimacy during political revolutions. Focusing on Russia and Vietnam during their adoption of communism, this project analyzes political propaganda from either nation’s revolutionary period by questioning its ability to relate and call upon national history, cultural values, and moral concerns. This analysis functions to understand the efficacy of the rising regime’s propaganda in producing a state conceived as legitimate by the citizenry. In asking this question, the project advocates for a conception of political legitimacy not determined by the state’s regime type, but rather determined by the life and perspective of the citizen.

propaganda, revolution, Soviet Union, Vietnam, political legitimacy, communism

Political propaganda can, and has, determined the outcome of wars, regimes, and campaigns. But while propaganda’s success in the world of war and regime have been well documented, not nearly as much attention has been paid to how the efficacy of the propaganda distributed during a nation’s “revolutionary period” is related to the political legitimacy that a regime experiences once the revolution is over.1 This relationship between revolutionary propaganda and regime legitimacy can begin to be answered through a study of the revolutionary periods of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Situating these two countries at the core of our analysis allows us a degree of universalizability, as these nations held different motivations for regime adoption, different revolutionary periods, and different outcomes: the USSR is no longer a communist state, and Vietnam is.

This project will uncover the relationship between emerging regime propaganda and long-term regime legitimacy through a historical and cultural overview of each country in reviewing the existing propaganda. This historical and cultural overview will work with the history experienced prior to and the cultural norms experienced during the nation’s revolutionary period. The purpose of examining the propaganda from these countries with the contextual backdrop of their existing culture and history, is to facilitate an understanding of how each state’s approach to propaganda interacts with their people’s history and culture, for the purpose of evaluating the propaganda’s efficacy. The existence of communist propaganda during the revolution and either nation’s historical timeline, indicates that communism was not accepted in these places, and as such the state’s propaganda at that time is considered “successful,” if it is able to convince the public of that their regime’s ideology and authority is legitimate. And so, to uncover the efficacy of Soviet and Vietnamese propaganda, a determination about their success in legitimizing themselves must be made. Through such a project, it will become apparent that propaganda that fails to assure its citizenry that their sociological and moral needs are being met, will not produce a citizenry that legitimizes its regime. This conclusion is the very thing motivating this project, and gives it meaning and purpose; for if we understand sociological and moral needs to be a foundational requirement of legitimacy, it becomes rapidly apparent that political legitimacy is not based in the procedural2 but in the physical and psychological needs of the citizenry.

I. Creating the Method

Because the regimes in question have radically different historical and cultural paths to power, to avoid confusion the parameters of the investigation will be set up first, followed by a focus on each state’s application separately. The purpose of this study is to utilize political propaganda during revolutionary periods to understand what causes the citizenry to produce political legitimacy. But, to conduct such an analysis in an organized way one must first define the methods of dissection for propaganda, the logic behind equating regime legitimacy to propaganda efficacy, and the tools used for gathering legitimacy data.

The following method is a novel means of analyzing propaganda, and is rooted in our specific research question. Most propaganda analysis works to understand either the psyche of the subject or the author, but in this project, we are interested in how the historical and cultural zeitgeist exposes the efficacy of a piece of propaganda in times of revolution. The caveat of “in times of revolution” is particularly important because propaganda in times of war and regime is working along the margins, attempting to pull those “on the fence” into the fold with a much broader base of support. This is not the case in times of revolution, and as such the propaganda must play with broad cultural and historical understandings to recruit, in the beginnings of the ideological revolution, and maintain, in the beginnings of the regime revolution, a base of support.

The goal of our analysis is to catalog the methods used, the sentiments invoked, and the targeted parties. To understand the methods, sentiments, and targets for a given piece of propaganda we will investigate the author, the means of distribution, and the design elements. In investigating the author, the first piece of our analysis, we are able to grasp at motivations and intended effects that might not be blatantly obvious by just the propaganda alone by closely considering both designer and commissioner. The second piece, cataloging the means of distribution is a process done by contextualizing the propaganda’s form, including not only the medium, but the method and demographic reach of distribution. The third piece, design elements include the historical and cultural symbolism that would have been understood by the target audience, resonance of message, language usage, and emotional appeals. These aspects allow an understanding of the propaganda as it would have been understood by the target, complete with the environment in which the subject encounters said propaganda. This three step data collection process will allow us to catalog the methods used, the sentiments invoked, and the parties targeted.

The logic behind equating regime legitimacy to propaganda efficacy is rooted in the nature of the propaganda we are dissecting. Because the pieces of propaganda involved in this project are produced at the beginning of a communist regime, their primary goal was to ensure that the targets of their propaganda found their regime to be a legitimate one. Because of this, a piece of propaganda discussed in this project can be considered as succeeding in its mission, or achieving a high efficacy rate, when the propagandist is able to convince their target that the propagandist’s regime, is a legitimate form of governance. Thus, if efficacy is understood to mean success in the mission of convincing individuals of a given regime’s legitimacy, it is understandable that one would assume that the best metric for studying efficacy would be empirically measuring political legitimacy. The most famous technique of measuring legitimacy was uncovered by Tom Tyler, who is often credited as the foundational scholar in the field of empirical legitimization studies, and involves correlating the rate of a population that holds the sentiment that one ought to obey the laws of their government with the rate of a population that deems their government legitimate. About the relationship between legitimacy and the existence of a duty to obey, Tyler says that “the perceived obligation to obey is the most direct extension of the concept of Legitimacy.” His justification for this is that because an individual experiences a duty to obey the law when an individual respects and reveres the state and its laws, Tyler understands the duty to obey the state as being the actualization of finding one’s state legitimate.3 This understanding of legitimacy is rooted in process based legitimacy, a concept that proports that if the procedures a regime type legitimate then automatically so too is the regime. For example, if we understand a democracy to be a legitimate way to rule, then any country that rules via democracy is automatically legitimate, with no care for the context of their regime.

However, I do not believe this method to be productive, or capable of producing valid results. Take the example above, that any country ruled by a democracy is automatically legitimate. What of a country that, though democratic, fails to provide for their citizenry? What of a country that, though political leadership is secured without election tampering, the election system (including campaign regulations, party divisions, and the public’s access to accurate information) is not conducive to an informed citizenry that are fully equipped to make good decisions for themselves, their families, and their country but instead benefits the election of leadership that is fundamentally harmful to the republic? Such a simple conception of political legitimacy is incapable of considering the complexities of political reality.4

These questions, and the attention to context and reality they demand, push me to align myself with the model of political legitimacy of Jeffery Lenowitz.5 Jeffery Lenowitz, argues in his book Empirical Measurements of Legitimacy, argues that process-based legitimacy is an incomplete characterization of legitimacy, as true legitimacy involves a moral and sociological aspect that process-based legitimacy is unable to account for.6 Lenowitz’s model concedes that the processes utilized by a government matter, but they matter in the context of the cultural understandings of those that are being governed, because to be truly legitimate a regime must be morally compatible with the citizenry’s specific historically and culturally informed belief system.

Lenowitz’s model of legitimacy means that the empirical measurement of legitimacy is extraordinarily difficult to accomplish, due to the innate limitations of polling. As such, to measure legitimacy in the context of propaganda efficacy this project will utilize a two step model, in which the early propaganda of a regime is analyzed for the existence of the types of arguments that would substantiate a valid cultural and moral claim to legitimacy, followed by an analysis of the trends in the empirical approval ratings of the state during the remainder of its existence, or existence thus far. The first step, involving a close reading of individual pieces and collections of propaganda, is to substantiate the claim that the propaganda is making an argument for legitimacy that would have worked within the public to produce such a sentiment. The second step, evaluating the trends in government approval throughout the regime, allows for an understanding of how strong the original claim of legitimacy produced by early regime propaganda truly was, for if a state has a strong enough argument for legitimacy, the citizenry will have a more durable approval for said state.

Before this two-step analysis begins, I would like to make clear the limitations of this paper. The research conducted towards the history and culture of a state, and the production and reception of propaganda is hindered on two fronts: language and history. I have sourced translations where I can, but I have no training in Russian or Vietnamese, and so the information provided here is limited to english studies and translated pieces on the subject, all of which were considered in the research and production of this paper. Additionally, due to the highly regulated nature of the regimes in question, there is very little data on citizen sentiment toward their regime, or the production of the propaganda.

III. Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

When inquiring into the revolutionary period of Russia, leading up to the instatement of Marxist-Leninist Communism, there are several dates offered. Some categorize the beginning of Russia’s communist revolution in relation to dates of party creation, revolutions, and government appointment. The creation of a political timeline is deeply tied to the project at hand, and thus, for this project, the most helpful mark of the beginning of the revolutionary period is the publication of Vladimir Lenin’s political pamphlet “What Is to Be Done?” in 1902. This pamphlet marks the beginning of the Bolshevik movement as this pamphlet and its ideas led to the fracturing of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party into the Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin who advocated for revolution via armed violence and the Mensheviks, who believed peaceful revolution was possible through legal reform and unions. This period of revolution of course comes to an end with the end of the Russian Civil war in January of 1920.7

On January 5th, 1918, the Bolsheviks invalidated the election results of the Constituent Assembly, which awarded power to the Mensheviks, and inducted themselves as the ruling party over the State. The Russian civil war that followed saw the formation of a coalition of those who opposed the Bolsheviks who joined ranks and attempted to overthrow the Bolsheviks, to no avail. The historical landscape leading up to the Russian Revolutionary period can best be understood as being deeply dissatisfied and disillusioned with the presence of nobility and a ruling class, an aggravation with war, and an intolerance for the ongoing lack of welfare and poor living conditions faced by many Russians in the early 1900’s. This reality was astutely confronted by the Bolsheviks who made their slogan “Peace, Land, and Bread” during the 1917 revolution.

As a result of the existing conditions pre-revolution, the Bolsheviks not only had to convince Russians that theirs was a plight solvable by the Bolsheviks, but that the rewards of communism was worth the “root-and-branch destruction of the patriarchal structure of the peasant family, Orthodox Christianity, and private land ownership-in short, the abolition of the traditional village.”8 This desperation for legitimacy led to Lenin “and his commissar of enlightenment, Anatolii Lunacharskii’s emphasis on ‘invented traditions’ [as] a key aspect of the campaign to capture public enthusiasm, inculcate novel ideas, and implant loyalty in a semiliterate population accustomed to the elaborate pageants and visual imagery of the old regime and the Russian Orthodox Church.”9 The Russian people, having been immersed in various monarchical governments who pulled their authority to rule from traditional conservatism and divine right theory, were in luck, for just as Marxism is a political theory with imbibed with an element of historicization, Marxism-Leninism had the very same quality, in the spring of 1918, before the Civil War in Russia was even won, he decree that the statues representing the old Czars and the “old ways” be replaced with monuments of a number of historical figures who, “in the Bolshevik master narrative, anticipated and prepared the way for the” new way of life in Russia.10

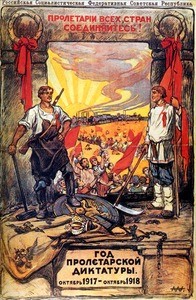

This propaganda scheme worked alongside the curation of the iconography for who the Russian worker, that the Bolsheviks praised so highly, was. It also worked to provide the Russian people with a visual representation of the “tradition” that was being invented, and just “as in the religious art of the Orthodox tradition, a set of standardized images was created, depicting worker heroes (saints) and class enemies (the devil and his accomplices).”11 Even a step further, it was not uncommon for the political pamphlets to take on “religious overtones[, with] Lenin depicted as a Christ-like figure, ready to die for the people’s cause.”12 A famous example of this is Aleksandr Apsit, a “God proletarskoi diktatury oktiabr’ 1917—oktiabr’ 1918” or Year of the Proletarian Dictatorship, October 1917—October 1918.13 See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Another facet of political society the Bolsheviks had to overcome was the Russian peasantry. There were a number of problems with the peasantry, namely that they were largely illiterate and incapable of comprehending the language of revolution. As well, by their allegiance they pledged often to their village community first and the Russian nation second. Further, they were resistant to change, particularly when that change came at their expense. On the first account, it is important to note the unique position of the ignorance of the Russian peasantry combined with the drastic change a socialist regime meant for the way of life for farmers, as all private land was soon to become public land that the peasant farmers were expected to toil to feed the entirety of Russia, created a situation in which it was very important the peasantry understand and accept the Bolsheviks. A huge obstacle that stood in the way of this was that the peasantry that was literate, an exceptionally small number, still did not understand the terminology of the communist party.

In their article on the matter, “The Russian Revolution of 1917 and Its Language in the Village,” Orlando Figes explains that “[t]he terminology of the Revolution was a foreign language to most of the peasants (as indeed it was to a large proportion of the uneducated workers) in most parts of Russia.”14 This bore an environment in which there was a deep desire for what Figes coins as “explanatory literature,” which sought to explain what these new words meant, not only for the revolution and the new government, but for the peasants’ role in their new world.15 This propagandistic explanatory literature found a foothold in sections of the newspaper, coined “Letters from the Village” and “From a Soldier,” which sought to act as such an explanatory literature. A translated excerpt from one such newspaper reads

“Your conscience says it’s sinful to think about yourself while your brothers spill their blood… Make a sacrifice, as we soldiers are doing to defend you. We are just to say this.”16

The diction here is calling upon religious sentiments, making an appeal to the peasantry’s traditional sentiments not only to godliness but to the authority of man, and soldiers specifically. Not only is the usage of “sinful,” pulling at the strings of the peasantry’s mind, but the demand to “make a sacrifice,” would have been particularly effective for a population that is not only extremely religious, but who believed that “if [they] accepted their lot, if [they] were hardworking… [they] would have the most [they] could expect from [their] society: food, family, and a respectable place in the village.”17 For more than being traditional and religious, the peasantry was a pragmatic people, a people who knew that success, but more likely mere survival, requires sacrifice.

As for their resistance to change and duty to their village, Barbara Clements’ “Working-Class and Peasant Women in the Russian Revolution, 1917-1923” is particularly enlightening. She explains that to the peasantry, not only was there little difference between the tsarist or Bolsheviks or otherwise, as “often peasants responded to the Soviet officials who first ventured into the countryside with much the same contempt they had shown the tsarist or Provisional Government officials.”18 This was in part because the revolution had brought not only lawlessness into the area, but had utterly demolished the economy, as “fewer and fewer manufactured goods were available, and inflation was destroying the value of the ruble, [and] with so little to buy in town peasants [relied] on subsistence agriculture and black-market dealing.”19 To make an already harrowing economic situation even worse, when the Russian Civil War began in 1918, women lost their husbands who had narrowly survived WWI in the thousands and were suddenly destitute. The destitution of millions of Russians, as peasants totaled over 80% of the population of Russia, was made even worse by the blatant disregard for the health and needs of the peasantry, as the Bolsheviks prioritized the working man, and viewed the peasant as “backward and conservative.”20 As such, they were frequently ignored by the Bolsheviks who “address[ed] most of their meetings, conferences, speeches, and written propaganda to working-class women.”21 Interestingly, though politically the Bolsheviks held a “commitment to and plans for female emancipation, [and] shortly after seizing power, the Bolsheviks had instituted civil marriage and no-fault divorce and had declared the full legal and civil equality of woman,” their depiction of women in political propaganda was extraordinarily sparse until 1919, when they incorporated a female assistant to serve beside the famous male blacksmith. An example of her iconography can be found in “Chto dala Oktiabr’skaia revoliutsiia rabotnitse i krest’ianke” or “What the October Revolution gave the woman worker and the peasant woman.”22 See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The only other example of women in propaganda from the revolutionist period was L. Radin’s “Smelo, tovarishchi, v nogu!” or “Boldly, Comrades, March in Step!” which is an extraordinary appeal to tradition, the specifics of which would have been utterly incomprehensible to the vast majority of the Russian public.23 See Figure 3. She holds very strong illusions to Greco-Roman ideals of republicanism, and the depth of the painting can only truly be understood when compared with Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People at the Barricades (see Figure 4) which “Smelo, tovarishchi, v nogu! is a blatant allusion to.24 In the figures we see that the dead bodies have been substituted for rubble, perhaps a comment on the differences in purpose and method between the French Revolution, the subject of Delacroix’s piece, and the Russian Revolution of 1917, the subject of Radin’s. Lenin’s blatant acceptance and advocacy for the use of armed violence for revolutionary purposes makes the substitution of dead bodies for ruble on account of fear for negative associations unlikely, meaning that the change is likely to be indicative of the Russian Revolution’s emphasis on industrialization.

II. The Socialist Republic of Vietnam

Though the history of the Vietnamese people as a whole is important contextual information, the era that will be the primary focus of this study is the “revolutionary” period leading up to the adoption of a communist regime. This period spans, roughly, from June of 1925, the inception of the Revolutionary Youth League of Vietnam until April 30th, 1975, the fall of Saigon. The rationale behind beginning the revolutionary period with the induction of the Revolutionary Youth League of Vietnam, is not only because this organization would evolve into the Communist Party of Vietnam, which is the sole ruling party of Vietnam but because it was formed to be “a nursery for the training and education of committed Marxists” and was understood to be the first step in convincing the public of the efforts of communism.25 The fall of Saigon marks the end of the Vietnam War, and the beginning of the unification of Vietnam under Communism, ending the Vietnamese revolutionary era and creating the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

The French Indochina war was the first conflict within the revolutionary period in Vietnam, and was a fight between Hồ Chí Minh’s army, the Viet Minh and the French occupation in Vietnam. France had been colonizing Vietnam since 1887, enacting horrific legal and social realities onto the indigenous Vietnamese. This colonization by the French came after centuries of Chinese attempts to colonize the area in a similar manner. The French Indochina War came to its conclusion in 1954, with a stalemate between Hồ Chí Minh’s forces in North Vietnam, who had forced the French from the area, and the French, who still had control over South Vietnam, but signed the Geneva Accords, relegating their previous authority to the existing authorities in South Vietnam, on the condition that in two years’ time, the entirety of Vietnam would hold an election to dictate the curation of a unified Vietnamese government.26

The Vietnam War is intimately connected with the aftermath of The French Indochina War. Hồ Chí Minh had plans of Vietnam developing a socialist regime and South Vietnam wanted to promote a democratic republic, though the leader of South Vietnam, Ngô Đình Diệm, falsified elections, and both leaders disagreed emphatically with the others desired regime type and began fighting before the unification election required by the Geneva Accords could be carried out. Because both the French Indochina war and the Vietnam war, which together created a 26 year long age-of-war for the Vietnamese people from 1949 to 1954 and from 1955 to 1975 respectively, were fought to regain independence and unification in the aftermath of imperial actions, the struggles endured during this time were consistently connected with colonialism. This bred a hatred of colonialism and anything that reminded the Vietnamese people of colonialism, a facet of Vietnamese culture that Hồ Chí Minh, and the Communist Party of Vietnam often used to their advantage.

A manifestation of these anti-colonialism sentiments can be seen in the logical schematics involved in the Vietnamese public’s perception of communism as the remedy to colonialism’s capitalism. During the French occupation, the indigenous people of Vietnam were not afforded any civil liberties, nor were they allowed to participate in the “modern sector of the economy, especially industry and trade.”27 As such, “apart from the landlords, no property-owning Indigenous middle class developed in colonial Vietnam,” meaning that the only means of economic participation Vietnamese individuals could participate in was trade and barter, making industrialized capitalism, which the imperial French participated in during their time in Vietnam, seem not only foreign but colonial in nature.

In addition to this intellectual separation from colonialism, anti-Colonial became embedded in the very definition of what it meant to be Vietnamese, which is manifested in the representation of fault in the Vietnam War. By using “current events in terms of remembered experiences,”28 North Vietnamese Propaganda was able to curate an image of American involvement, as a manipulation of South Vietnam from an outside and historically imperial source attempting to keep Vietnam separate. Historically, this notation is backed by an understanding that the United States would not allow for the unifying election outlined in the Geneva Accords, which held that at the end of the French Indochina War, Vietnam would be separated into a North and South faction, and after two years, each side would democratically elect a sole ruling body. Because of the United States’ widely known policy of “containment,” North Vietnam felt that American involvement in the decision to reject a unifying election equated to, or could be portrayed as equating to, America as an imperial force determined to keep Vietnam separate and subjugated. If the propaganda could convince the Vietnamese people that America was the enemy, and that America was the reason for the conflict between the North and South, it did not have to convince them of the ideology, for that was a secondary concern.

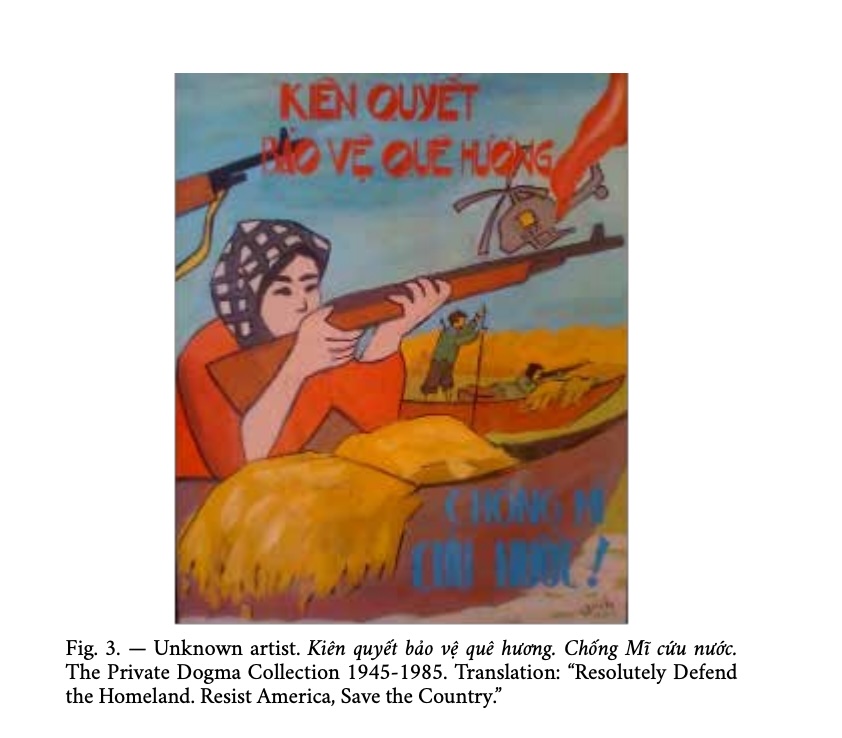

Indeed, a great deal of the propaganda of North Vietnam stems from the fact that their propaganda didn’t target ideology or attempt to convert its targets to communism. This is very consistent with the literature on Propaganda, as we understand now, due to Lazarsfeld and Katz’s theory of “limited effects” that propaganda has a much harder time convincing individuals ofgrandiose ideas instantly, because of the flow of opinions through interpersonal networks.29 An understanding of the war as North Vietnam against America, and thus colonialism as a whole not North Vietnam versus South Vietnam, can be seen in Kiên quyết bảo vệ quê hương. Chống Mĩ cứu nước, meaning “Resolutely Defend the Homeland. Resist America, Save the Country.”30 See Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Though related by virtue of origin to the anti-colonialist sentiment, a separate concern of the propaganda produced by North Vietnam, was the idea of the Vietnam war, or the War on America, as a means to unite Vietnam. This sentiment can be seen in Saigon’s “The Dogma Collection,” which showcases a number of pieces of propaganda that pushed the Vietnamese people to imagine and hope for a united Vietnam. In a number of the propaganda pieces, we see the lotus flower, a symbol for Buddhism, rebirth, and optimism, possibly representing either religious tolerance, an impossibility under French rule, or to the rebirth of a free nation and a unified people that will, like the lotus flower in nature, survive and grow no matter the conditions. In addition to these, the lotus flower may also be acting as a means for the “development and exploitation of direct emotional ties to the nation and its symbol,” to promote an association between the symbol of a nation and its ideals, which in this case was unification.31

This tactic was not only used with the lotus flower, but with Hồ Chí Minh himself as “North Vietnamese propaganda that references freedom, strength, victory, or other positive sentiments almost always contain images of either Hồ Chí Minh.”32 This was not just because Hồ Chí Minh was the leader of the North Vietnamese unification project, but because Hồ Chí Minh had, in the eyes of the public, successfully conquered imperial forces in the past, and thus he was a trusted source, and someone who had, could, and would rid Vietnam of outside control and restore Vietnam to a country of its own. Both of these motifs can be seen in Không có gì quý hơn độc lập, tự do, meaning “There is Nothing More Valuable than Independence and Freedom.”33 See Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Another very powerful symbol in the propaganda was the clothes the North Vietnamese people were depicted in. The garb North Vietnamese soldiers were seen wearing, were not military uniforms, or even combat appropriate pieces, but rather the clothing that was often worn by farmers, common ethnic clothing. They exchanged helmets for scarves and straw hats and the infamous American bullet-proof vest for a simple shirt. While it is true that “[t]heir clothes called to mind a people unaffected by Western influence and thereby framed the war as a fight for Vietnamese ethnicity and identity against corrupting foreign invaders,” this depiction also helped bolster the communist cause, as it framed the war in terms of the peasantry and the average Vietnamese person, people that communism seeks to lift up and protect.34 This message of the common man stepping up to fight and sacrifice for his country, was particularly successful in alleviating the reputation of the North’s violent guerilla tactics utilized against their opponent, many of which are considered to be cruel and unusual war crimes, such as deadly booby traps, forced suicide bombing, and extensive violence against civilians. Though today, we understand that some of the worst atrocities of the Vietnam war came from the American Soldiers,35 by the very nature of the Vietnam as a civil war, despite its publicity stating otherwise, the North Vietnamese crimes against the South Vietnamese needed to be dealt with, and by curating an image of the Viet Cong as a untrained civilian army fighting tooth and nail for survival, leaving their patty fields to fight, forgoing the luxury of American bootcamp, North Vietnam was able to justify their tactics. This can be seen in Dân tộc khổ đau là vì ai, meaning “The People Suffer Because of Who?”36 See Figure 7.

Figure 7.

IV. The USSR and Vietnam Compared

This project has accomplished its primary task of cataloging the various means and methods for propaganda curation and development alongside the cultural and historical climate of its country. As outlined above, it is now time to hold those propaganda tactics in comparison with the sociological and moral needs of the citizenry. Beginning with the Soviet Union, as evidenced above, the Russian people, or at least the 80% that made up the peasantry, were traditional and pragmatic, and while the mistreatment of the people by the Tzar instigated a rebellion against his rule that was out of character for the Russian people. An example of this can be seen in the story of Aleksandra Rodionova, a twenty-two-year-old who is describing the mood that gripped her and many others from her class in those days:

“I remember how we marched around. The streets were full of people. I did not know then, I did not understand what was happening. I yelled along with everyone, “Down with the tzar” when I thought, ‘But how will it be without the tsar?’ it felt as though a bottomless pit opened before me and my heart sank.37

But the diversion from their norms does not mean that his replacement had been given the leeway by the Russian people to violate those needs. Evaluating the Bolsheviks’ application of propaganda, it is clear that they are not meeting the needs of the peasantry, as the propaganda they put out is ineffectual to the people that need it most because it is not comprehensible to them. This ineffectual propaganda usage, when combined with the devastating economic state during and after the Revolution of 1917, explains very clearly why the Bolsheviks lost the election in 1918. Their decision to overthrow the election and move forward with ruling over the country despite their loss, only further proves this point. We can see the effects of these decisions in the peasantry’s actions, as they “fought the government tooth and nail for many years— sometimes actively, most often passively,” as well as their refusal to work their land to feed a country whose regime they didn’t support. This unwillingness, even in the face of punishment, was the actualization of the existing peasant sentiment that the good of the village and the family exists over that of the country.38

As for the efficacy of the North Vietnamese propaganda, Stephens Young notes that “Vietnamese invest true authority with those who possess the quality of uy tin (moral legitimacy).”39 Meaning that so long as Hồ Chí Minh’s actions, at least through his establishment of the regime, were considered to be moral, the Vietnamese people were willing to follow him. Alagappa’s book, Political Legitimacy in Southeast Asia, concedes that “[t]he literature in English on post-1945 Vietnam rarely discusses the legitimacy of the socialist regime,” but that is not cause for panic. Because there is a gap in the statistical data on the perceived legitimacy, or any data via election numbers, as the elections in the Socialist Republic of Vietnam have always been falsified, the judgment of Vietnam’s propaganda efficacy will fall on the back of its ability to consider the sociological and moral needs of its people.40 As noted earlier, the primary sociological and moral concern of the Vietnamese people was their disdain for imperialism, and the revival of their identity as a post-colonial nation. The propaganda created by North Vietnam accomplished this well, and it was sure to paint the blame on the outside imperial forces of the United States, so well in fact that the war is commonly referred to as “the American War,” and so North Vietnam’s crimes against the South Vietnamese army and its allies are morally defensible, as North Vietnam was simply attempting to unify Vietnam and rid the Vietnamese people of the plight of colonialism. As stated earlier, though the propaganda emitted during the war from North Vietnam was rarely ideological in nature, this does not take away from North Vietnam’s success in convincing the populus of their political legitimacy. This is a particularly effective argument in the face of Young’s insistence that political authority is significantly more rested in moral permissibility and legitimacy, than ideologically.

Through this project, it has become apparent that conveying the connection of a regime to the sociological and moral concerns of the citizenry, even amidst fighting and famine, are instrumental in securing initial regime legitimacy. At a time in history rife with a desire for change, when revolutionary ideals are constantly swirling both interpersonally and parasocially, it can be easy to forget that propaganda can change the hearts and minds of a nation piece by piece, until the citizenry is ready to accept the brutal slaughter of its own people. The ability of North Vietnam to convince its people with limited resources and against impossible odds that Hồ Chí Minh had their best interest at heart, by paying attention to the fears and the history of their people, should shine a very bright light into the face of the possibilities of propaganda to mold the values of its targets until they are unrecognizable.

But, perhaps more importantly that a warning of the powers of propaganda, this project should push the reader to ask themselves: does your regime suit your sociological needs and moral values? This project acts as an study of propaganda’s use and reach, and it serves to validate a legitimacy that incorporates the citizen’s experience, but the true purpose of this piece is to remind the reader that when we allow legitimacy to be more than a mere synonym for democracy, as process based legitimacy would have us do, we can begin to remember that our institution’s primary function is to care for its people. A state that forgets this is subject to valid inquiries on its status as legitimate. So again, I ask: does your regime consider your sociological needs and moral values?

Notes

- Jowett, Garth S., and Victoria O’donnell. Propaganda & Persuasion. Sage publications, 2018. pg 7 ↩︎

- A guiding sentiment in contemporary legitimacy studies ↩︎

- Tyler, Tom R. “Procedural Justice, Legitimacy, and the Effective Rule of Law.” Crime and Justice 30 (2003): 283–357. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1147701. pg 310 ↩︎

- This view is pervasive in legitimacy studies, and because this work is, at its core, engaging with that field, it is necessary to expose the reader to the field’s prominent convictions. ↩︎

- For the purpose of this study. A normative argument for subjective legitimacy is not within the scope of this project. ↩︎

- Lenowitz, Jeffrey A. “On The Empirical Measurement Of Legitimacy.” Nomos 61 (2019): 293–327. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26786319.4-5. ↩︎

- Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Russian Civil War.” Encyclopedia Britannica, March 2, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/event/Russian-Civil-War. ↩︎

- Clements, Barbara Evans. “Working-Class and Peasant Women in the Russian Revolution, 1917-1923.” Signs 8, no. 2 (1982): 215–35. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3173897. pg 220 ↩︎

- Bonnell, Victoria E. 1997. “Iconography of Power : Soviet Political Posters Under Lenin and Stalin.” Studies on the History of Society and Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press. pg 22 ↩︎

- Bonnell, Victoria E. “Iconography of Power : Soviet Political Posters Under Lenin and Stalin.” pg 21 ↩︎

- Bonnell, Victoria E.“Iconography of Power : Soviet Political Posters Under and Stalin.” pg 23 ↩︎

- Figes, Orlando. “The Russian Revolution of 1917 and its Language In The Village.” The Russian Review 56.3 (1997): 323-345. https://www.jstor.org/stable/131747 pg. 344 ↩︎

- Aspit, Aleksandr. “God proletarskoi diktatury oktiabr’ 1917—oktiabr’ 1918” Translation: “Year of the Proletarian Dictatorship, October 1917—October 1918” ↩︎

- Figes, Orlando. “The Russian Revolution of 1917 and its Language In The Village”. pg 325 ↩︎

- Figes, Orlando. “The Russian Revolution of 1917 and its Language In The Village.” pg 327 ↩︎

- Figes, Orlando. “The Russian Revolution of 1917 and its Language In The Village.” pg 327 ↩︎

- Clements, Barbara Evans. “Working-Class and Peasant Women in the Russian Revolution, 1917-1923.” pg 217 ↩︎

- Clements, Barbara Evans. “Working-Class and Peasant Women in the Russian Revolution, 1917-1923.” pg 218 ↩︎

- Clements, Barbara Evans. “Working-Class and Peasant Women in the Russian Revolution, 1917-1923.” pg 218 ↩︎

- Clements, Barbara Evans. “Working-Class and Peasant Women in the Russian Revolution, 1917-1923.” pg 218 ↩︎

- Clements, Barbara Evans. “Working-Class and Peasant Women in the Russian Revolution, 1917-1923.” pg 229 ↩︎

- Author Unknown. “Chto dala Oktiabr’skaia revoliutsiia rabotnitse i krest’ianke” Translation: “What the October Revolution gave the woman worker and the peasant woman.” (1919) ↩︎

- Radin, L. ““Smelo, tovarishchi, v nogu!” Translation: “Boldly, Comrades, March in Step!” ↩︎

- Bonnell, Victoria E. “Iconography of Power : Soviet Political Posters Under Lenin and Stalin”. pg 69 ↩︎

- Duiker, William J. “The Revolutionary Youth League: Cradle of Communism in Vietnam.” The China Quarterly, no. 51 (1972): 475–99. http://www.jstor.org/stable/652485. pg 480 ↩︎

- Spector, Ronald H. “Vietnam War.” Encyclopedia Britannica, March 2, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/event/Vietnam-War. ↩︎

- Osborne, M. Edgeworth, et. al. “History of Vietnam.” Encyclopedia Britannica, October 30, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/topic/history-of-Vietnam. ↩︎

- Stern, Paul C. “Why Do People Sacrifice for Their Nations?” Political Psychology, vol. 16, no. 2, 1995, pp. 217–35. JSTOR, doi. org/10.2307/3791830. pg 230 ↩︎

- Jowett, Garth S., and Victoria O’donnell. Propaganda & Persuasion. pg 7 ↩︎

- Unknown artist. Kiên quyết bảo vệ quê hương. Chống Mĩ cứu nước. The Dogma Collection 1945-1985. Translation: “Resolutely Defend the Homeland. Resist America, Save the Country.” ↩︎

- Le, Tuyen. “Rehumanizing the War in Vietnam: Propaganda Art and the Northern Perspective.” A Journal of Undergraduate Research in the Interdisciplinary Humanities: 105. ↩︎

- Le, Tuyen. “Rehumanizing the War in Vietnam: Propaganda Art and the Northern Perspective.” pg 108 ↩︎

- Unknown artist. Không có gì quý hơn độc lập, tự do. The Private Dogma Collection 1945-1985. Translation: “There is Nothing More Valuable than Independence and Freedom.” ↩︎

- Le, Tuyen. “Rehumanizing the War in Vietnam: Propaganda Art and the Northern Perspective.” pg 112 ↩︎

- Cookman, Claude. “An American Atrocity: The My Lai Massacre Concretized in a Victim’s Face.” The Journal of American History 94, no. 1 (2007): 154–62. https://doi.org/10.2307/25094784. ↩︎

- Unknown artist. Dân tộc khổ đau là vì ai? The Private Dogma Collection 1945-1985. Translation: “The People Suffer Because of Who?” ↩︎

- Clements, Barbara Evans. “Working-Class and Peasant Women in the Russian Revolution, 1917-1923.” pg 226 ↩︎

- Dean, Vera Micheles. “Our Russian Ally.” https://www.historians.org ↩︎

- Young, Stephen B. “Unpopular Socialism in United Vietnam.” Orbis 21 (1977): 227-239. pg 228 ↩︎

- Alagappa, Muthiah. Political legitimacy in Southeast Asia: The quest for moral authority. Stanford University Press, 1995. pg 257 ↩︎

References

Alagappa, Muthiah. Political legitimacy in Southeast Asia: The quest for moral authority. Stanford University Press, 1995.

Bonnell, Victoria E. 1997. Iconography of Power : Soviet Political Posters Under Lenin and Stalin. Studies on the History of Society and Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press. https://search.ebscohost.com.

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Russian Civil War.” Encyclopedia Britannica, March 2, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/event/Russian-Civil-War.

Clements, Barbara Evans. “Working-Class and Peasant Women in the Russian Revolution, 1917-1923.” Signs 8, no. 2 (1982): 215–35. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3173897.

Cookman, Claude. “An American Atrocity: The My Lai Massacre Concretized in a

I’m Victim’s Face.” The Journal of American History 94, no. 1 (2007): 154–62. https://doi.org/10.2307/25094784.

Dean, Vera Micheles. “Our Russian Ally.” (1945) https://www.historians.org

Duiker, William J. “The Revolutionary Youth League: Cradle of Communism in Vietnam.” The China Quarterly, no. 51 (1972): 475–99. http://www.jstor.org/stable/652485.

Figes, Orlando. “The Russian revolution of 1917 and its language in the village.” The Russian Review 56.3 (1997): 323-345. https://www.jstor.org/stable/131747

Jowett, Garth S., and Victoria O’donnell. Propaganda & Persuasion. Sage publications, 2018.

Le, Tuyen. “Rehumanizing the War in Vietnam: Propaganda Art and the Northern Perspective.” A Journal of Undergraduate Research in the Interdisciplinary Humanities. pg 105-114.

Lenowitz, Jeffrey A. “On The Empirical Measurement Of Legitimacy.” Nomos 61 (2019): 293–327. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26786319.4-5.

Osborne, M. Edgeworth, et. al. “History of Vietnam.” Encyclopedia Britannica, October 30, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/topic/history-of-Vietnam.

Spector, Ronald H. ‘Vietnam War.” Encyclopedia Britannica, March 2, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/event/Vietnam-War.

Stern, Paul C. “Why Do People Sacrifice for Their Nations?” Political Psychology, vol. 16, no. 2, 1995, pp. 217–35. JSTOR, doi. org/10.2307/3791830.

Tyler, Tom R. “Procedural Justice, Legitimacy, and the Effective Rule of Law.” Crime and Justice 30 (2003): 283–357. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1147701.

Unknown artist. Dân tộc khổ đau là vì ai? The Private Dogma Collection 1945-1985. Translation: “The People Suffer Because of Who?”

Unknown artist. Không có gì quý hơn độc lập, tự do. The Private Dogma Collection 1945-1985. Translation: “There is Nothing More Valuable than Independence and Freedom.”

Unknown artist. Kiên quyết bảo vệ quê hương. Chống Mĩ cứu nước. The Dogma Collection 1945-1985. Translation: “Resolutely Defend the Homeland. Resist America, Save the Country.”

Young, Stephen B. “Unpopular Socialism in United Vietnam.” Orbis 21 (1977): 227-239.

Citation Style: Chicago