Caregiving Then and Now:

Disability in ancient humans challenges common notions of our ancestors

by Isabella Burhanna, Anthropology

Anthropology has long sought to identify different aspects of human nature and their presence in the human past. A subfield of anthropology, bioarchaeology, focuses on the physical and biological manifestations of past human life left in the skeletal record and other biological remains. The study of disabilities is probably thought to be a modern world problem by many people, but bioarchaeology has continued to show that challenges faced by humans today are not as uncommon in the past as we may have thought. A lot can be learned about humans by studying them in the past and present. Healthcare access and support for caregiving are limited in the United States. By comparing modern caregiving with with a bioarchaeological study from the Late Archaic, this paper outlines the need for more careful consideration and support of the “community of care” that allows individuals with a disability to live fulfilled lives.

bioarchaeology, caregiving, disability, healthcare

Introduction

In the United States, disabilities combined with improper access to healthcare are especially detrimental to many Americans’ lives. Nine percent of adults over the age of 18 years report difficulty or inability in at least one domain of functioning. This percentage only increases with age group, yet only 3% of total national health expenditures, $3.8 trillion, are allocated to home health care, and only 4.5% are attributed to nursing care and retirement facilities (CDC, 2020). This lack of access is even more impactful in individuals who lack a “community of care,” a support network of people who contribute to their quality of life. This paper includes an in-depth review of a bioarchaeological study, revealing that humans in the past and present are more similar and this community of care is more intrinsic to human nature than some people may have previously thought. It then discusses caregiving in America and other areas of the world, further emphasizing that greater access to support and financial relief for caregivers is essential in improving American healthcare and reinforcing a community of care.

The Bioarchaeological Evidence

Many people do not think people thousands of years ago lived with disabilities. A study of a juvenile female’s remains from the Late Archaic (around 3000 years ago) revealed that she suffered from Osteogenesis imperfecta type IV (Vairamuthu & Pfeiffer, 2018). This genetic disease leads to significant skeletal deformities and compromises mobility and independence. Hunter-gatherer populations like that of the individual studied were usually highly mobile and showed little evidence of occupational stability or resource management to support living in one place for an extended period of time.

Not being able to walk and needing assistance in care would not have been easy, especially in this context. The fact that this individual lived to the age of 16 years with her disease reveals a lot about her family group and challenges assumptions we make about past humans. It is also a comforting case to study, showing that people in the past have struggled with things more similarly to modern humans than we thought.

The individual in this case, who will be called the juvenile moving forward, was excavated in Ontario between 1968 and 1977, but an in-depth review of the pathologies of her skeleton was not published until Vairamuthu & Pfieffer’s (2018). The juvenile’s skeleton shows many notable skeletal deformities and defects, with a lack of density (referred to as gracility) and fragility seen throughout every bone, especially at their developing ends. Her age at death estimated from her skeleton and teeth indicates an age of 16, but her overall growth is consistent with that of a 6-8 year old. Despite this, radiographs of her bones show no noticeable disruptions in development, so her lack of size was not due to environmental factors and was likely due to a condition that was consistently stunting her growth, leading to a loss of mobility.

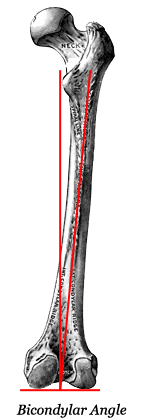

Her lack of mobility is supported by the fragility and gracility of her skeleton because bones not pressured by movement will remain delicate. The most supportive evidence of this is in the bicondylar angle of her femur. This refers to the angle that the axis of the femur creates with the femoral head and in humans, this feature is directly correlated with the ability to walk on two legs (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. An image of an adult human femur showing a typical bicondylar angle. (Odysseyadventures.ca)

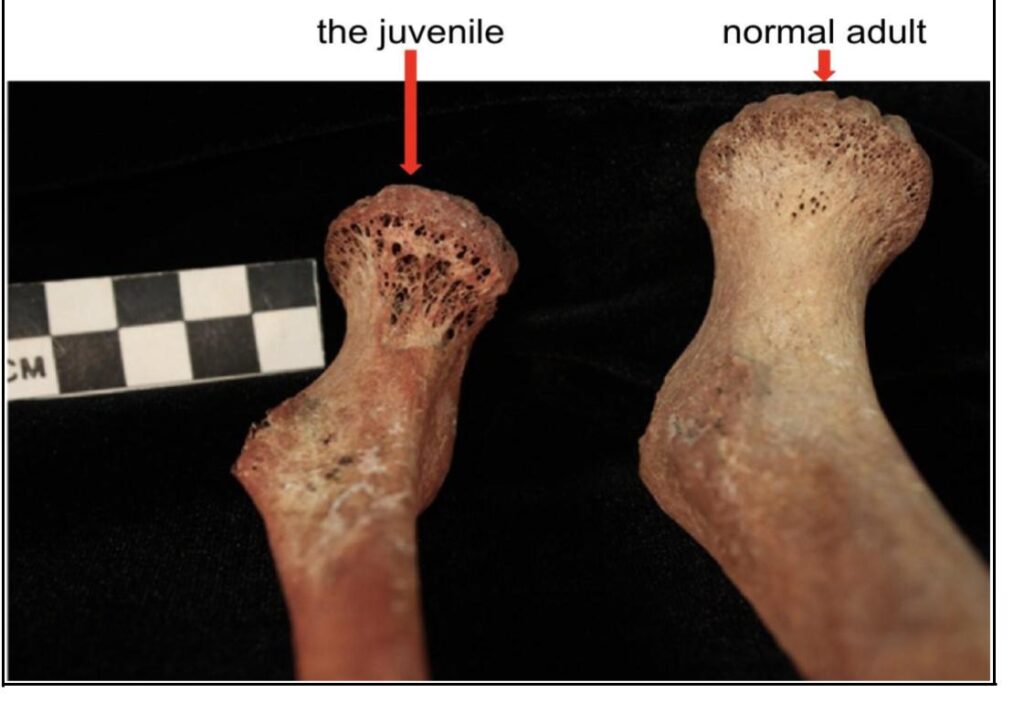

Infants do not walk, not needing a bicondylar angle to support the weight of their body. With time and increased weight bearing, children eventually develop a bicondylar angle similar to that in Figure 1. In the population the juvenile was found in, bicondylar angles of adults ranged between 6.6°and 13.5°. The juvenile’s is 1.7°, falling into the range of infants. This lack of an age appropriate bicondylar angle along with the fragility of her bones strongly support that she was non ambulatory and would have had to be carried around by someone else (Figure 2). Along with lower limb evidence of immobility, measurements of her upper limbs in comparison with other juveniles reveal that the torsional strength of her arms was less than half of that of a properly developed juvenile at the time, resulting in little to no upper limb mobility.

Figure 2. Comparison of the juvenile’s femur with that of another adult of the time. The bone around the end of the femur is clearly more porous and fragile. The angle at which the femur cuts from the head is also not sharp in the juvenile compared to the normal adult (Vairamuthu & Pfeiffer, 2018). “Normal” is a term commonly used in the literature which refers to a physically typical adult.

The juvenile’s jaw and cranium also maintained the same gracility as the rest of her skeleton, although her teeth and jaw were well developed. By death she had lost many of her adult teeth and those left had a high amount of mineralized plaque, which correlates to a diet of softer foods. Overall, the researchers concluded that the pathologies of the juvenile’s skeleton most closely align with the symptoms of Osteogenesis imperfecta type IV because this specific type spares no part of the skeleton in its progress and affects all limbs equally.

A New Perspective on Modern Healthcare and Caregiving

Considering the context of her hunter-gatherer population, the case of this juvenile female is especially interesting. Her age at death (16 years), disease status, and the mobile lifestyle of her population reveals the strength of her family group. Her survival would have required practices such as occupational stability and food storage that are rarely evident in the archaeological record of the Late Archaic. It begs for a new perspective of past humans that many people likely do not hold, as a common belief of ancient humans is that they were barbaric or undeveloped. Clearly for an individual facing a disease like the juvenile female, this could not have been true. Her family group would have had to pay a lot of time and organization in taking care of her, surrounding her in a “community of care,” and giving her what many Americans probably wish they could give their loved ones today.

On the other side, the assumption that past humans lacked sophistication can also be disproved considering how present caregiving is today. Many nations have developed caregiving and healthcare networks, and in America, healthcare is often a primary topic in every election. Caregiving is not unique to this time, and understanding its importance to present humans highlights how it could have been important for past humans. Most people like to think of themselves as a good, caring person at their core. Anthropology has long debated this aspect of human nature. Do we inherently all care and love or are we all derived from a violent being? Studying the case of this juvenile in the context of caregiving today challenges this assumption that humans are intrinsically violent. The amount of care she was likely given in order to survive definitely softens our idea of past humans and points to the importance of caregiving in the human experience. A care network is not something new to humans at all; it is just becoming more present as our populations are larger and age farther.

Because of unequal access to healthcare, the structure of most Americans’ work lives, and a lack of preparation in the healthcare system for the increasing diversity of individuals requiring caregiving, supporting a family member who has a disability is very difficult (Schulz, 2016). Studies have taken on the task of defining “family care” and caregiving as geographically unlimited and cross-cultural, meaning it is a common theme in all cultures and countries (Gibson, 2020). Yet, it does not seem to persist like this in America. Many people are forced to place their loved ones in care facilities to keep their job or remain financially stable. Even when families have the ability to give care themselves, in America and in other countries, the consequences of this care are financially, emotionally, and socially costly, and this cost should be recognized. In 2021 alone in America, “About 38 million family caregivers in the United States provided an estimated 36 billion hours of care to an adult with limitations in daily activities. The estimated economic value of their unpaid contributions was approximately $600 billion” (AARP, 2023).

Still, there is no system in place to deal with the expanding need for caregiving. Other countries like the Netherlands and Germany have funding provided for long term care of elderly individuals. Similarly, countries like France and China provide affordable ways for parents to care for their children while at work, easing the financial burden of caregiving (Gibson, 2020). Overall, many countries have developed ways to handle this burden, although it is not universal nor all-encompassing in any country. In relation to the bioarchaeological study, it is relevant to look at these experiences of caregiving because it shows the community of care is as a human trait that could not just have appeared in modern times.

Conclusion

With life span increasing to almost 76 years and only rising, it is clear that integrating financial relief for caregiving into government policy is something that could be crucial to reinforcing a community of care that all individuals deserve (CDC, 2020). National expenditure on healthcare totals to trillions of dollars, but only a small fraction of this is allocated to caregiving and disability support. This problem facing individuals with disabilities is not a uniquely modern issue. Past humans are often labeled as barbaric or unrefined, representing a less superior form of humans, but bioarchaeology and the information it gains from past populations proves that this reduction of humans is incorrect. Opposite of this, caregiving in the present also represents a challenge to this label because its prevalence is not something that could have simply appeared this century. Human support for each other through community, in the past and the present, supports the fact that a more open and careful consideration of caregiving is necessary to improve the lives of many Americans. As the bioarchaeological study revealed, a “community of care” could be more basic and necessary than we thought, even 3000 years ago.

References

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). FastStats – Homepage. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats

Gibson, B. (2020). What the U.S. Can Learn About Caregiving From the World. The American Prospect. https://prospect.org/familycare/what-the-us-can-learn-about-caregiving-from-the-world/

Odysseyadventures.ca. (2024). Human Bipedalism. https://www.odysseyadventures.ca/articles/humTax/article_bipedalism.html

Reinhard ,S., Caldera, S., Houser, A., and Choula, R. B. (2023). Valuing the Invaluable: 2023 Update Strengthening Supports for Family Caregivers. AARP Public Policy Institute. https://doi.org/10.26419/ppi.00082.006

Schulz, R. (2016). Summary—Families Caring for an Aging America. National Library of Medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK396392/

Vairamuthu, T., and Pfeiffer, S. (2018). A juvenile with compromised osteogenesis provides insights into past hunter-gatherer lives. International Journal of Paleopathology, 20, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpp.2017.11.002

Acknowledgements: I want to extend a huge thank you to Kate Pitts for letting me write such a long paper for a “Pop Media” assignment and supporting me throughout the writing process. I would also like to thank Dr. Reitsema for inspiring me in more ways than I can count throughout her classes and for believing in me and my goals!

Citation Style: APA