The Significance of Researcher Positionality Throughout the Research Process

by Jennifer John Britto

In this work, I discuss the necessity in applying one’s positionality throughout their research process from beginning to end by utilizing my own research process as an example. Positionality impacts the topic of study, methodology, and how I interpret the results of the study. Positionality also brings to light assumptions regarding the participants and the topic of study, which allows the researcher to address the implications of these assumptions on the study itself. When discussing positionality, it is essential to see what power dynamics are at play. Therefore, not only should the identities of the researcher be factored but also the identities of the participants are important as well. Power dynamics can create tensions between the researcher and participants, affecting the data. Also, positionality can influence the way the researcher portrays the research analysis as it can be shown as damage-centered or in a more holistic view. As a result, it is necessary to address how the researcher’s identity and experiences relate to the research topic. Furthermore, as a researcher, one must show care to their participants and the communities of the participants in the form of refusal, which also takes into account the idea of power dynamics, damage-centered research, and creating a holistic perspective.

positionality, refusal, damage-centered, power dynamics

Introduction

Through my research process, I have understood the significance of positionality in one’s research methodology. I will be arguing for the necessity of positionality throughout one’s research process by providing my own research process as an example.

Research Topic

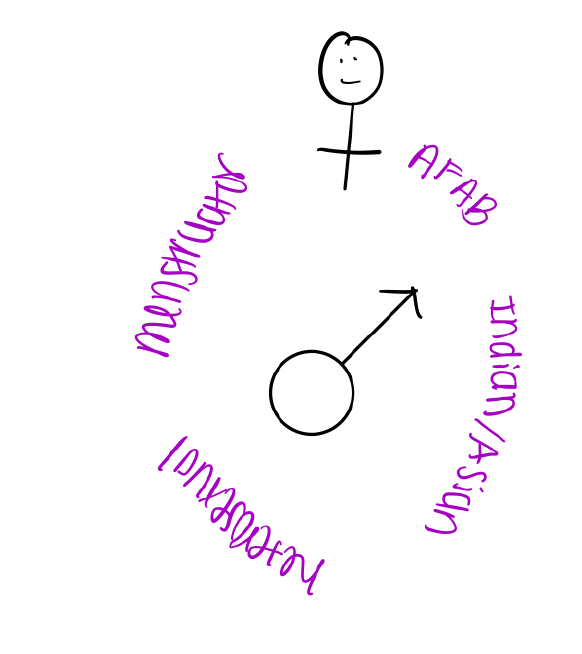

Even though both non-menstruating and menstruating individuals perpetuate the stigma of menstruation, I would like to understand how menstrual knowledge, both accurate and inaccurate, is transmitted to assigned male at birth (AMAB) individuals. I chose to focus on AMAB perspectives because assigned female at birth (AFAB) perspectives have already been widely researched in the context of menstruation.

Research Question

The research question I would like to focus on is: How is knowledge about menstruation transmitted to AMAB undergraduate college students?

My guiding questions are: Did they receive any prior menstrual knowledge? Was the knowledge accurate? What sources did they receive knowledge from?

Significance of Study

I hope that through the findings of this study, more effective education about menstruation can be developed. Existing misconceptions allow for menstruation to be stigmatized by maintaining the power dynamics between menstruators and non-menstruators (Owen, 2022). This study will facilitate the dismantling of these power dynamics.

Defining Positionality

In this argument, I define positionality as the identities, beliefs, and experiences that define an individual. Each aspect influences how an individual views certain topics, their interactions with others, and how they analyze results.

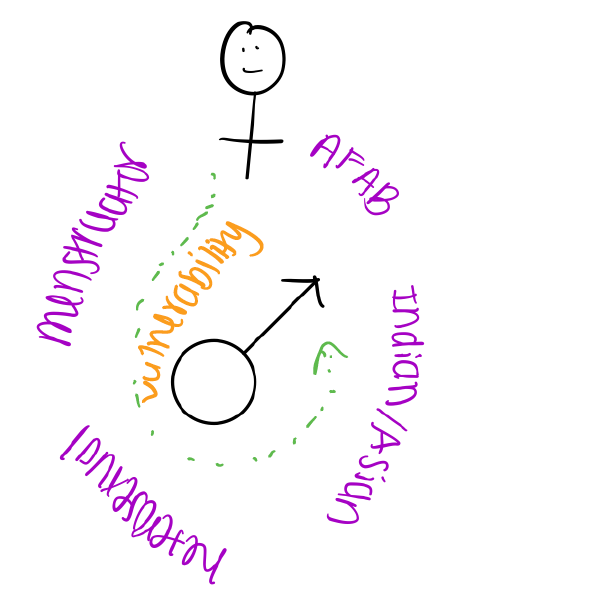

My Positionality

My Positionality

I highlighted the identities that I think most strongly impact my perspectives in the context of this research project: namely, South Indian, AFAB, cis-gender woman, menstruator, Christian, and upper-middle class socioeconomic status. By defining my position, I can understand the pre- existing assumptions I have due to my identities and reflect on how they will impact my research (McCorkel & Myers, 2003).

How does my positionality relate to my research subject?

With my socioeconomic status, I have had access to healthcare and educational resources on menstruation, which has allowed me to debunk many misconceptions such as premenstrual syndrome (PMS) being a universal experience for menstruators. However, my sex education in Georgia was very limited, so my biomedical knowledge is predominately from being a menstruator myself, as well as the content covered in my college-level biochemistry classes. My women’s studies major facilitated my passion in reproductive health, furthering my knowledge in menstruation.

How did my positionality inspire my research project?

My upbringing and public education in Georgia made me very aware of the lack of health literacy surrounding women’s reproductive health, which inspired me to conduct research on menstruation.

In public school, all I received was a five-minute informational video on menstruation, and my mom was too hesitant to educate me as she was taught that menstruation was a taboo.

When we first got our periods, my cousin and I had a South Indian ritual symbolizing our transition into womanhood. Despite the celebratory nature of the event, our experiences created an alternative taboo-centered perspective. Even though we were brought up in different places, we both suffered from the misconception of menstruation as dirty and impure.

Now, I look out for my period because I understand that monthly menstruation is a sign of health indicating that my body is working normally. I felt empowered by gaining a better understanding of my own body. I am privileged to have access to healthcare. I wanted to identify where the stigma and taboos originated and how they are perpetuated in the present-day in order to reduce misconceptions.

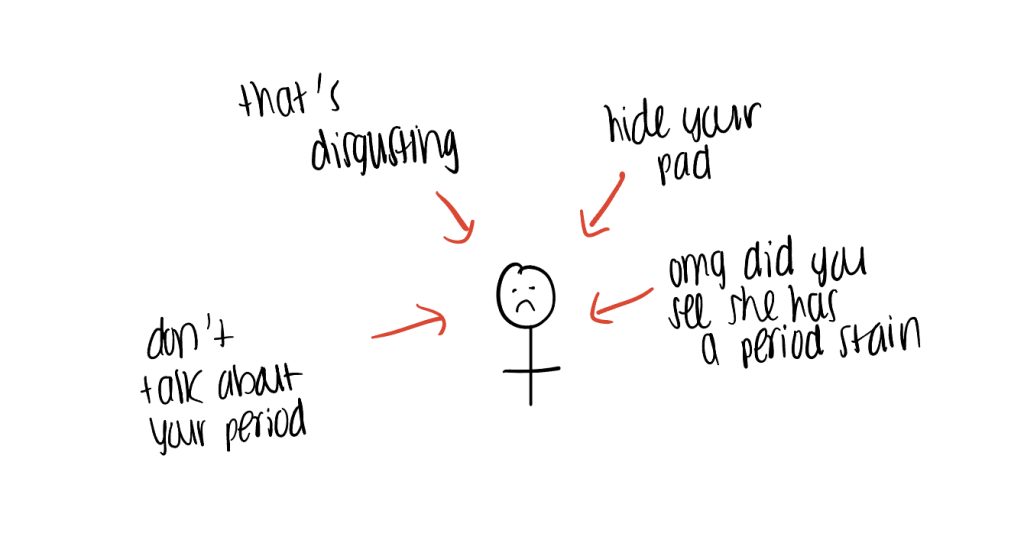

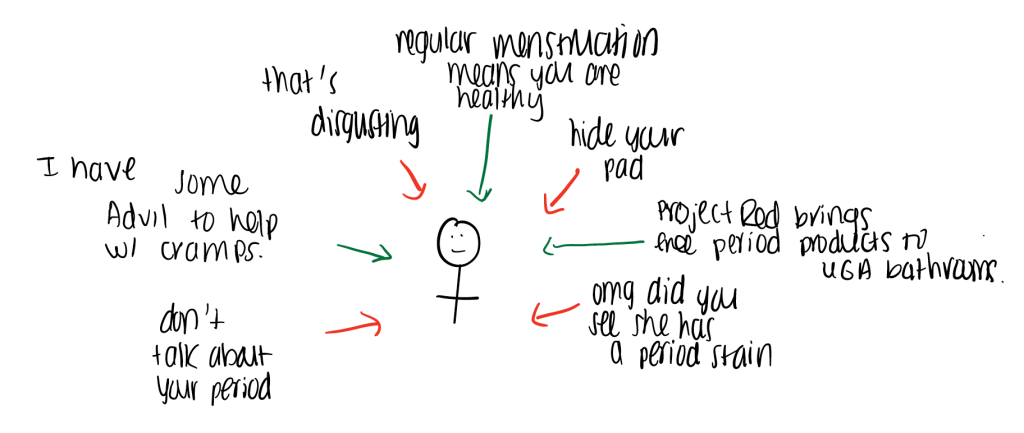

Initially, I felt my experiences were very damage-centered

As an Asian-American, my Indian culture plays a large role in my menstrual experience, as I experienced both celebratory and taboo-centered messaging. Since I perceive my experiences as mostly negative, I should be mindful of this bias when conducting my analysis. I do not want my experiences to result in a damage-centered analysis.

However, I developed a more holistic view after reflecting upon my privileges and positionality

Methodology of Study

For this study, I collected data through semi- structured interviews. Then, I analyzed the interviews using thematic analysis, through which I can identify patterns in the narratives. This method prevents my assumptions from biasing the results, and also illuminates unknown factors. I chose this methodology based on my position as an outsider relative to my participants, who are AMABs.

Positionality and Methodology

Due to my identity as a 21-year-old female, AMAB subjects may feel uncomfortable discussing the subject of menstruation with me. Likewise, participants may view me as an outsider to their experiences due to my identity as an AFAB and/or differences in race or ethnicity. In previous

interview-based studies, researchers noted that their outsider status was dynamic because the dialogue exchanged and credibility established created a new emphasis on different parts of the researchers’ identities (Rivers-Moore, 2016).

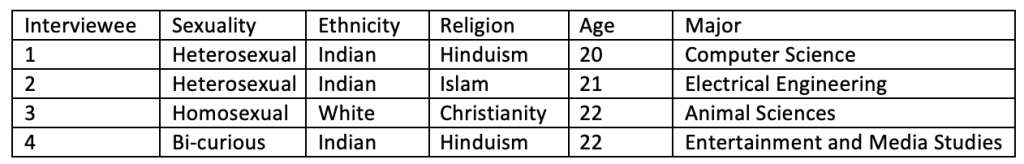

Interviewees

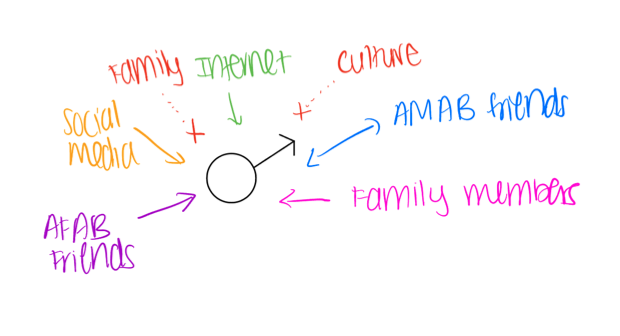

For this study, I found my participants by posting my study on social media and asking if anyone was interested in participating in this study. This was a useful method because my social media followers are predominately undergraduate students, who are the focus of my study.

However, this meant that the participants would be in my social circle, and most likely knew me.

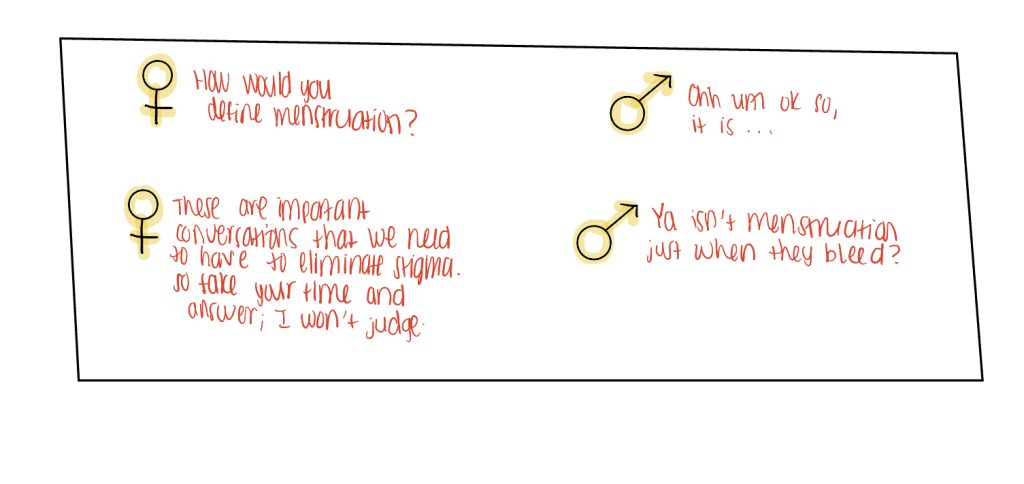

Participant Responses to my Positionality

- Initially uncomfortable

- Overcompensated for being a man

- Scared to say wrong answers

- Often said: “I think” or “Potentially”

- More comfortable after I shared my personal experiences

- Most did not ask any follow-up questions about biomedical knowledge I shared

Due to my identity as an AFAB and menstruator, the participants were uncomfortable discussing the topic, and were reluctant to claim that they knew what they were talking about. Also, they often stated that men were stupid or that men were the issue. They were more open to discussion after I shared my experiences, and they realized that I was not judgmental. I did notice that some were not interested in learning, which may be due to my AFAB identity or ethnicity.

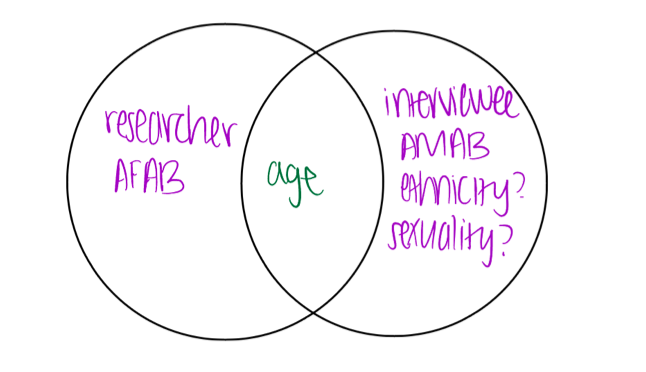

Power Dynamics

I recognize that my position as a researcher creates a power dynamic in my favor (Mullings, 1999). The interviewee may feel inclined to answer questions even if they are uncomfortable. I realized there were other power dynamics as well due to my ethnicity, gender identity, and sexual orientation. Age was a commonality between my interviewees and I, so I do not think that made a significant impact on the results. I tried to mitigate the researcher-participant power dynamic by giving the interviewees the opportunity to read over my analysis and tell me to remove any aspects that they felt were not representative of them or made them uncomfortable.

Tensions in Positionality

Since I am AFAB, participants felt uncomfortable speaking to me about menstruation. The interviewees were hesitant to give me their raw, unfiltered responses, as they were worried I would judge them. Also, they attempted to overcompensate for being an AMAB by blaming men for most menstruation stigmas, which I felt like would not have happened if the interviewer was not AFAB. The discomfort I felt throughout the interviews reminded me of Ahmed’s discussion of feminist theory as ‘difficult’ and ‘disruptive,’ whether it is at a family table or in the context of research (Ahmed, 2017).

Self-Reflections

During the first few interviews, I was more closed off or awkward about sharing my personal information. This was reflective of how menstruation has always been a taboo in my life. However, after multiple interviews, I noticed myself becoming more comfortable and more open to sharing my experiences. My openness altered the atmosphere of the interview, and it made data collection easier. My experience reminded me of Hoang’s reading, where she explains that in order to gain the participants’ trust, it was imperative that she be vulnerable with them as well (Hoang, 2015).

Building Connections

My experiences were connected to Rivers- Moore’s experiences as well; she was an outsider to both the sex workers and the men she was interviewing. I was able to overcome most of the participants’ views of me through conversation and building connections throughout the interview. Likewise, Rivers-Moore discusses how identity is dynamic because the dialogue exchanged and credibility established created new emphasis on the different parts of the researcher’s identity (Rivers-Moore, 2016). As participants began to understand I was not judging them, and ceased viewing me as an outsider, I was able to gain more insight into their answers.

Similarly, Hoang explains how she was an outsider in her research as well, but becoming vulnerable allowed her to build relationships and learn from her interviewees (Hoang, 2015). I applied her insights to my own research by talking about my personal menstrual experiences to my participants.

Results of Study

Based on the interviews, most of the participants had menstrual knowledge transferred to them through very similar forms. Most of the interviews discussed that they were able to gain knowledge about menstruation, associated symptoms, cravings, etc. Also, these conversations often sparked interest in my participants to further research the subject on their own via the Internet. Additionally, one interviewee mentioned TikToks they had seen about menstruation, which indicated that social media played a role in knowledge transmission. Interviewees also identified that they were taught by family members (specifically their mothers) and their respective cultures that menstruation is a taboo.

Identifying my Biases

One of my interviews was with a white, homosexual man, and it brought to light many of the assumptions and biases I had regarding menstruation. First, I was surprised that he had not had many conversations about menstruation with his AFAB friends. I realized that I had previously held the incorrect assumption that homosexual males, in comparison to heterosexual males, would have more conversations about menstruation because AFAB individuals would be more comfortable talking to them.

Additionally, I thought that white culture did not have many taboos regarding menstruation, and that Indian culture held more taboos. However, I learned that white households also had many taboos. This interview brought to light how my positionality caused many biases, but this methodology prevented those assumptions from affecting the data findings.

Positionality and Holistic Analysis

Tuck explains how when many sensitive topics are discussed, the aspects that are highlighted are mostly damage-centered (Tuck, 2009). I was concerned that my negative experiences with menstruation would only create further bias in my analysis.

Furthermore, Tuck and Yang discuss how academia often utilizes collected data to depict narratives as damage centered when refusal is not practiced (Tuck & Yang, 2014). Refusal is the decision taken by the researcher and participants to intentionally omit certain sensitive parts of research as a form of respect and care to the researched community (Tuck & Yang, 2014).

Positionality, Refusal, and Holistic Analysis

While discussing cultural practices, Interviewee 4 stated, “Well I know one of my friends who is Indian but from a different area can’t remember where, well apparently her family had a huge party for her first period.”

Initially, I questioned if refusal should be used because this is a ritual specific to South Indian culture. However, I do not think this makes my culture vulnerable, so I do not think refusal is necessary. I do not just view this as a data point, but also as a way of acknowledging that Indian communities celebrate menstruation rather than only having taboos.

I hope to reject the Western perspectives of India surrounding menstruation and clarify misconceptions about South Indian culture in relation to menstrual taboos, which I can do by producing a more holistic portrayal of South Indian culture.

Conclusion

My methodological process helped me understand how positionality is dynamic.

Even if I was initially an outsider, connecting through culture, ethnicity, and/or personal stories allowed me to become an insider.

Furthermore, my positionality shaped my perspectives and gave rise to many assumptions, but it also provided me with background knowledge for this research and the opportunity to share my experiences with my participants.

Coming into this project, I viewed my positionality as an obstacle. Now, I realize that it also facilitated my research and helped me understand why I approached my analysis the way I did.

Bibliography

Ahmed, S. (2017). Living a Feminist Life. Duke University Press.

Hoang, K. (2015). “Appendix: The Empirical Puzzle and the Embodied Cost of Ethnography.” In Dealing in Desire: Asian Ascendency, Western Decline, and the Hidden Currencies of Global Sex Work, pp. 181-195. University of California Press.

Mullings, B. (1999). Insider or outsider, both or neither: some dilemmas of interviewing in a cross-cultural setting. Geoforum, 30(4): 337-350

Owen, L. (2022). Researching the Researchers: The Impact of Menstrual Stigma on the Study of Menstruation. Open Library of Humanities, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.16995/olh.6338

Rivers-Moore, M. (2016). “Methodological Appendix.” In Gringo Gulch: Sex, Tourism, and Social Mobility in Costa Rica, pp.179-188.

Trask, Haunani-Kay. (2019). “From a Native Daughter.” In Race, Class, and Gender: Intersections and Inequalities, pp.18-24.

Tuck, E. (2009). “Suspending damage: A Letter to Communities.” Harvard Educational Review 79 (3): 409-428.

Tuck, E. and Yang, W. 2014. “Unbecoming Claims: Pedagogies of Refusal in Qualitative Research”. Qualitative Inquiry, 20(6): 811-818.

Citation Style: APA