A Methodological Reflection About Autoethnography

by Alina Baiju

In this paper, I argue that when autoethnography is used for research purposes, collaborative and relational ethics should be taken into account because true confidentiality is difficult to maintain. This is particularly important when the researched population is heavily stigmatized, as is the case with my research project. I chose to research factors affecting undergraduate students coping with an ADHD (Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder) diagnosis, with the goal of identifying how individual differences between undergraduate students translates into self-perception and identification with ADHD. Although my initial plan was to conduct autoethnographic research, I realized that the availability of my identity as the author and researcher of my own life greatly compromises the confidentiality of the people in my life. In order to follow the principles of relational ethics, which considers how the people in researchers’ lives are affected by autoethnographic research, I opted against autoethnography out of respect to the people in my life who value their privacy. Collaborative ethics, on the other hand, makes sure that research participants are treated properly. While conducting my interviews, I noticed that sharing my own experiences greatly increased participant comfort during the interview process. This form of reciprocity reduced the preexisting power differential between the researcher and participant, as it showed participants that the researcher was willing to be as vulnerable as the participants were asked to be. Researcher positionality should also be considered when conducting data analysis to avoid biased results. Overall, this was a valuable learning experience; I will continue taking these principles into account in the future, both inside and outside the context of feminist research.

autoethnography, reciprocity, researcher accountability, relational ethics, collaborative ethics, positionality

February 22, 2023

Introduction

I argue that when autoethnography is used for research purposes, collaborative and relational ethics should be taken into special consideration because true confidentiality is difficult to maintain. When conducting autoethnography— the analysis of personal experiences with the goal of applying the knowledge to research findings— it is easy to overlook the need for external consent based on the definition alone (Ellis et al., 2011). It’s your own life after all, so why exactly is others’ permission needed? The reason stems from the limited ability for ‘side characters’ in the researcher’s own life to remain unidentified when the researcher’s identity is provided. Collaborative ethics refers to the appropriate treatment of research participants in a project that includes “an autoethnographic component in research primarily focused on the stories of others,” and relational ethics addresses how others are portrayed in any form of autoethnography (Lapadat, 2017, p. 598). These considerations influenced how I approached my research project, which involved factors affecting undergraduate students coping with an ADHD (Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder) diagnosis, with the goal of identifying how individual differences between undergraduate students translates into self-perception and identification with ADHD.

Through this project, my perspective on desire-based research expanded to account for how the people in my life might be affected by my autoethnographic research. Desire-based research refers to the intentional holistic representation of researched populations rather than focusing only on their suffering, as described in Eve Tuck’s Suspending Damage (Tuck, 2009). Although my topic was initially much broader, I chose to narrow it down to what I really wanted readers to take away from my research experiences: the importance of relational ethics when conducting autoethnographic research, and how that ties into the idea of desire-based research. My paper offers an in-depth discussion of methodological and ethical concerns that arise when conducting autoethnographic research, and how to maintain a desire-centered framework throughout the research process. Hopefully, my experiences with both autoethnography and desire-based research can help provide guidance to other feminist students who are thinking about designing their own research project.

My report is organized in the form of a paper, which I believe is the most effective way to present my findings because it gives me the most space to discuss them while maintaining confidentiality. I will start off with “Desire-Based Research,” where I will describe how I developed my methods to portray my research subjects in a more holistic manner and how it differs from existing representations. Afterwards, I will proceed to the section titled “Methodology and Ethical Considerations,” which describes my methods in greater detail and how they evolved alongside my understanding of reciprocity. The next section is “Positionality,” which describes my experience interviewing participants with different demographic backgrounds and how that affects their responses. Then, I discuss Relational Accountability, which explains why I opted against including autoethnographic data in my results. The final section is “Discussion and Conclusions,” where I situate my work within a larger methodological context.

Desire-Based Research

While conducting my data collection activities, I tried to take a more desire-based approach to how individuals diagnosed with ADHD perceive themselves and their condition instead of making negative assumptions through a damage-centered lens. In the context of my research project, current literature tends to be more damage-centered, as it focuses on actions societally perceived as negative rather than how each patient perceives their own actions. According to Barra et al., “little is known about how to counteract unfavorable effects, [and] research on the use of stress coping strategies in adults with ADHD is scarce” because there is a greater focus on emotion dysregulation (Barra et al., 2021, p. 982). By explicitly stating that certain effects are unfavorable, it is implied that presentations of the condition are unfavorable, perpetuating negative perceptions of ADHD. By interviewing my participants about both positive and negative experiences, I developed my project to depict their experiences in a more holistic manner.

Furthermore, I wanted to add more qualitative content to the existing repertoire of literature surrounding ADHD. Current research quantitatively acknowledges the racial and ethnic disparities regarding access to ADHD diagnosis and treatment, but it doesn’t go into detail about the emotional well-being of the patients. I believe that it is important to explore how those factors affect the patients after receiving said diagnosis in order to humanize individuals diagnosed with ADHD, who are currently stigmatized. Both providing a more holistic view and humanizing research participants are characteristic of desire-based research (Tuck, 2009). Desire-based research is an important aspect of collaborative ethics because it allows participants to approve of how they are portrayed.

Methodology and Ethical Considerations

In addition to collecting autoethnographic data, I conducted three semi-structured interviews. The interviews were conducted with the goal of collecting more detailed qualitative data and gaining a better understanding of the lived experiences of the research subjects. My research question concerns the experiences of undergraduates with ADHD, and since I am currently studying at UGA (the University of Georgia) I was able to find participants for my study there. I chose to go with a semi-structured format because it allowed the participants to share only what they felt comfortable sharing and gave them the space to go on tangents if they wanted to. This also offered me the additional methodological benefit of seeing what topics participants were most comfortable speaking about.

At the beginning of each interview, I read out a verbal agreement that informed the interviewee of their rights. I made it clear that the interviewees could stop the interview at any point in time and had full freedom to refrain from answering any of the questions. I made sure that my participants were well aware that consent is ongoing, a “collaborative process which means that a no may come later in the course of the collaboration” (Bailey, 2015, para. 21). This addresses the collaborative ethics component of autoethnography. I wanted to convey to my participants that their contributions were “fully voluntary… and that the sharing context [was] nonhierarchical and noncoercive” to try to counteract the “preexisting power differential” acting in my favor because I am the researcher (Lapadat, 2017, p. 600). Due to the sensitive nature of my research topic, all of my interviewees were assigned pseudonyms. After the interview was recorded, I transcribed the interview and deleted the original recording, and interviewees had the opportunity to edit the transcripts to ensure that the collected data was representative of their views.

While analyzing the interviews, I noticed that reciprocity became particularly relevant. As the conversations proceeded, I started giving more information about myself and my own thoughts about the topics discussed. As Max Liboiron says in Transmissions: Exchanging, there is an “often hidden exchange that underpins all academic work,” and “reciprocity of thinking requires us to pay attention to who else is speaking alongside us” (Liboiron, 2020, p. 102). I was uncomfortable asking questions without answering them myself, so I felt that it was unfair to have the interviewees be the only ones in vulnerable positions—especially considering the personal nature of the questions.

As a result, I started offering my own takes on these issues after my interviewees answered, despite originally planning to be uninvolved, so there would be a more even exchange where both of us were vulnerable. I also made it clear to my interviewees that I was willing to answer any questions they had for me regarding my own experiences, which established a more comfortable relationship between us due to the reciprocal nature of the questioning. Opening myself up to questions about my own experiences made me a little more vulnerable. That, in addition to the conversational nature of the interview, made this topic much easier to discuss. Being reciprocal in the interview is an example of collaborative ethics because it is making sure that the power differential in my favor is reduced.

Positionality

In What Difference Does Difference Make? Position and Privilege in the Field, McCorkel and Myers “critically examine how ‘master narratives’ regarding race, class and gender shaped our effort to make sense out of our personal and professional experiences in the field” (McCorkel & Myers, 2003, p. 200). The ‘master narratives’ in question refer to the belief systems perpetuated by dominant groups that establish existing inequities as immutable (McCorkel & Myers, 2003). One of my interviewees was a 23-year-old gay white male who was assigned the pseudonym Gabriel. He has very different perspectives on pursuing accommodations in the workplace than me, which is potentially because he is a white man and I am a South Asian woman. Gabriel said that “in real-life scenarios… it is much easier to… talk to your employer” to ask for accommodations when compared to asking professors for accommodations in a classroom setting. On the other hand, I have always been taught to minimize any additional differences I have from the dominant group in professional settings—namely, white males—so I never viewed asking for accommodations in the workplace as an option. This belief shaped the question I posed to Gabriel around 12 minutes into the interview, which was “When you pursue accommodations in an academic setting, do you think it prepares you well for the workplace, where you might not get accommodations?” Gabriel’s response was to point out that accommodations can also be available in the workplace, where they might even be easier to obtain than in an academic setting. His response forced me to acknowledge how my positionality affected my assumptions about my interviewees in ways that I had not initially considered. It also highlights Gabriel’s relative privilege in the workplace as a white man, as he assumes that employers will be understanding when that might not be the case for more marginalized groups.

Cultural differences also affected how comfortable each participant felt sharing information. Gabriel said that he feels “like ADHD itself is really destigmatized in at least [his] culture, where everyone knows what it is” and he has “never come across negative connotations to it.” This acceptance of ADHD and related conditions within his own white culture translated to Gabriel feeling more comfortable sharing his diagnosis with other people, as he has “never faced any negative impact of… sharing it.” It also explains his increased willingness to accept accommodations because he doesn’t view them as stigmatizing. This differs greatly from the responses of both myself and my first interviewee, a 21-year-old South Asian woman assigned the pseudonym Nathalie. We were both less comfortable discussing our experiences with pursuing accommodations and sharing our diagnoses, as ADHD along with mental health conditions are not often discussed within South Asian communities.

In addition to impacting participants’ willingness to share their experiences, cultural perspectives on mental health can also affect how participants feel about themselves. My third interviewee was a 21-year-old queer half-Israeli woman who will be identified using the pseudonym Alya. She was not unaffected by the fact that she had to take medication; despite knowing “it makes [her] stronger” and “better at what [she] do[es],” Alya said that it also makes her “really sad sometimes when [she] think[s] about it.” This was not something that Gabriel was concerned about, but it was something I addressed in my own interview. Alya said that she is half-Israeli, and that her father does not consider mental health something of significance. My own culture also does not prioritize mental well-being, so one potential contributor towards a feeling of guilt towards having to use medication could be a cultural background where mental health is not paid much attention.

Overall, I kept seeing myself in my interviewees’ experiences, which could have impacted the way I presented their results. Going forward, I made sure to avoid trying to fit different experiences into my existing perspectives on the issue and made sure to obtain their consent at each subsequent step because consent is an ongoing process. This connects to collaborative ethics because I am the researcher here, and the power differential is in my favor. Therefore, I needed to be careful not to unintentionally misrepresent my participants’ experiences.

Relational Accountability

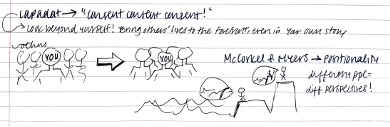

Figure 1: Visual depiction of Lapadat 2017 and McCorkel & Myers 2003

One of the primary issues that came up was the idea of relational ethics when conducting autoethnographic research. As discussed in the Relational Ethics section of Judith Lapadat’s Ethics in Autoethnography and Collaborative Autoethnography, “it is difficult to protect the anonymity of others mentioned in the story… even with pseudonyms for names and places, intimate others can be easy to identify, and they certainly can recognize themselves in a written account” (Lapadat, 2017, p. 593). I depicted this in Figure 1, which illustrates my understanding of Lapadat’s work. In other words, the ‘side characters’ in my own life story have lives of their own that can be negatively affected by the dissemination of my autoethnographic responses. (Fig. 1).

Although my initial intention was for my first interview to be autoethnographic and to be identified as such, I decided not to continue with that plan and instead found another anonymous interviewee. In my original interview, I mentioned several friends and relatives who have ADHD. Because ADHD is so stigmatized in social settings, particularly within the Indian-American community, having their medical information publicly available would not be the best course of action. It was of key importance to me to retain their confidentiality, especially considering the difficulties these individuals had while coming to terms with having the condition.

Another course of action I could have taken instead of finding a new interviewee was to change their relation to me; for example, to refer to them as members of the community. While that would be an effective tactic for the general public and potentially the general community, it would not prevent them from being identified by people who are familiar with my family structure— family friends, for example. There are very few people who are currently aware that the individuals in question have ADHD, but if they want to read my research that number would likely increase. Although I am generally okay with having my diagnosis revealed, I do not believe that it would be ethical for me to reveal the personal information of the people I mentioned in my account. As a result, I decided to maintain a higher degree of confidentiality by removing myself as an interviewee and finding another interviewee with a similar ethnic background.

Discussion and Conclusions

My research project focused on the lived experiences of my interviewees post-diagnosis, conducted with the goal of expanding the definition of coping to place more emphasis on how patients deal with the diagnosis itself. By collecting this data, I was able to add another dimension to existing research, which primarily concerns symptom management. By making sure to utilize a desire-based approach to my research, I hoped to provide a more holistic view of the stigmatized population I studied: undergraduates who have been diagnosed with ADHD. Furthermore, by making sure to consider how others in my life would be affected by any autobiographical information I included, I avoided breaching the privacy and trust of my participants. This project helped me realize the necessity of researcher accountability, particularly relating to collaborative ethics—especially while studying stigmatized communities. The effects of researcher positionality and inherent biases should be considered when conducting interviews and analyzing collected data, as shown in the reflections of the interviews with Gabriel and Alya. Furthermore, researchers should aim to achieve some degree of reciprocity with their research participants, as it reduces the power differential that favors researchers. Overall, this was a valuable learning experience; I will continue taking these principles into account in the future, both inside and outside the context of feminist research.

Bibliography

Ahmed, Sara. 2017. “Introduction: Bringing Feminist Theory Home.” In Living a Feminist Life, 1-18. Duke University Press.

Bailey, Moya. 2015. “#transform(ing)DH Writing and Research: An Autoethnography of Digital Humanities and Feminist Ethics.” Digital Humanities Quarterly 9(2).

Barra, S., Grub, A., Roesler, M., Retz-Junginger, P., Philipp, F., & Retz, W. (2021). The role of stress coping strategies for life impairments in ADHD. Journal of neural transmission (Vienna, Austria : 1996), 128(7), 981–992. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02311-5

Ellis, Carolyn, Adams, T., & Bochner, A. 2011. View of autoethnography: An overview. FQS Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Social Research, 12(1).

Lapadat, Judith C. 2017. “Ethics in Autoethnography and Collaborative Autoethnography.” Qualitative Inquiry 23 (8): 589-603

Liboiron, Max. 2020. “Exchanging” In Transmissions: Critical Tactics for Making and Communicating Research, edited by Kat Jungnickel, 89-107. MIT Press.

McCorkel, Jill A. and Kristen Myers. 2004. “What Difference Does Difference Make? Position and Privilege in the Field.” Qualitative Sociology 26(2): 199-231

Tuck, Eve. 2009. “Suspending damage: A Letter to Communities.” Harvard Educational Review 79 (3): 409-428.

Citation Style: APA