Shades, Not Colors

A Discussion on Choices Made in Oncology

by Megan Hong

In this fictional narrative, the reader follows the story of Stacy, a young woman with Stage III lung cancer, from her diagnosis to her death. Lung cancer, which is described as the abnormal cell growth and the following metastasis of lung cells, is one of the most common types of cancer; as well, it has one of the highest mortality rates out of any type of cancer. As Stacy’s lung cancer progresses, the physician has to make a series of decisions based on many factors, such as the conditions of Stacy’s pregnancy and her desire to save her baby, and the reader is able to witness how each decision makes an impact on Stacy’s mental and physical health. Through conversations with a practicing physician in psychiatric oncology and an undergraduate involved in cancer-related research, the reader is provided with various methods that help terminally ill cancer patients understand the reality of their disease and prognosis, and if current research in cancer therapies address the mental health of these patients. The article concludes that these decisions made by physicians and parents regarding their health are not always binary; rather, the choices that are made depend on many variables, some of which are controlled while others are not.

Key Words: cancer, psychiatric oncology, novel treatments

Cancer cells are the uncontrolled manifestation of a person’s normal cells. Each cancer has its own mind and personality of growth. With a sudden cancer diagnosis, patients often look to their physicians to guide them toward recovery with the expectation of a concrete, successful treatment plan. However, the answers to a win against cancer are not standardized; after all, it is a patient’s body against their own, and the road to recovery depends on many independent, uncontrolled variables. Decisions about cancer treatment are not binary choices. There are no simple questions and no simple answers. For physicians, what factors do they consider to make these decisions? When are cancer treatments doing more harm to a patient’s quality of life than physically benefiting them? Nothing in medicine, especially oncology, is black and white. In order to determine a best path forward, hopefully toward a cure, the doctor must know the patient and their desires when it comes to treatment.

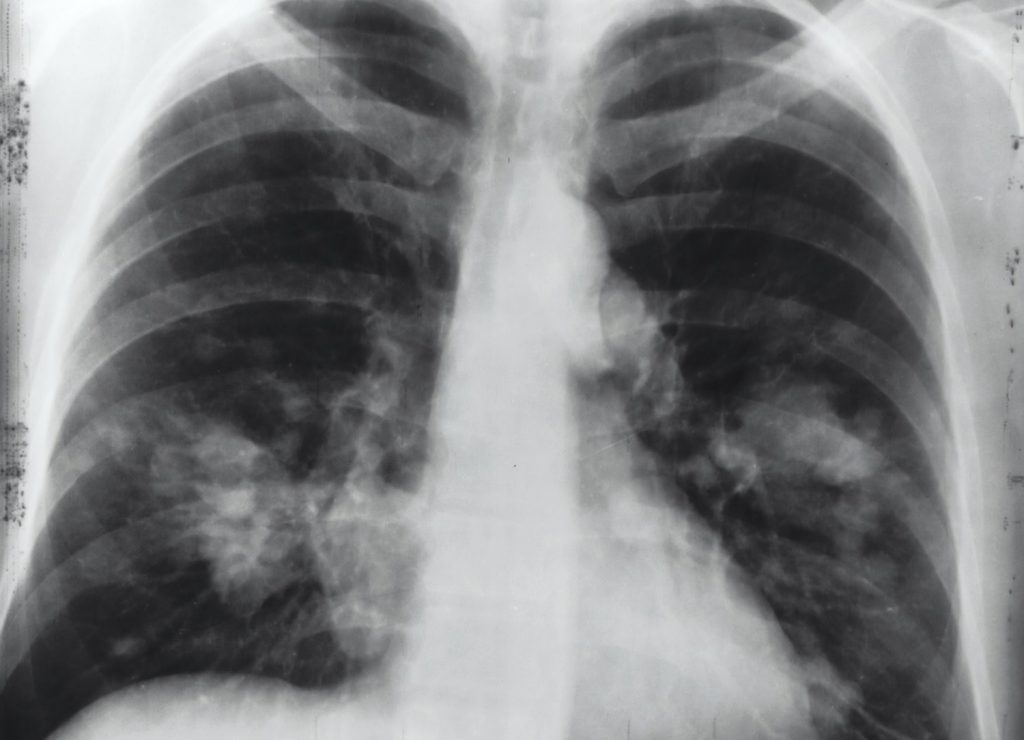

The air immediately gets cold. As she sits in the doctor’s office, she feels the hair on her arms stand up. The door handle turns, and the doctor walks in with a solemn look on her face. “Stacy, the biopsy reports have come in. You have a type of lung cancer called Non-small Cell Lung Carcinoma, and by the looks of your scans, we think it is Stage III and aggressive. We’ll be starting you on treatment as soon as possible, but this will be complicated by your pregnancy…” The words begin to blur as the thoughts in Stacy’s head become louder and louder. The only thing on her mind is the smell of fresh light pink paint that she had picked out ever so carefully for her baby. “Stage III lung cancer? She doesn’t even smoke. What about the baby? How will this work? She can’t possibly get radiation treatment,” her husband frantically interrogates the doctor. All eyes are on the physician. Her face remains solemn, and all of a sudden, it seems as cold as the room. “We will create a plan with a specialized oncologist and gynecologist. I will give you some time to process this information.” She promptly leaves the room. A dense silence hangs in the air.

With her recent diagnosis, Stacy and her husband are stunned and overwhelmed with the blunt reality she is facing. Soon, she will begin intensive therapy, which is notoriously no easy feat to overcome. Cancer treatments can have significant impacts on both the physical and psychological conditions of a patient. In a study conducted in 2014, localized Non-small Cell Lung Carcinoma patients were screened for changes in mental and physical health before and after treatment using a health-related quality of life (HRQoL) surveillance test. Researchers found that patients suffered from a significant physical detriment after their surgical operations. This, in turn, also had an impact on the patients’ mental health, as their new physical state limited them from participating in activities that were a part of their lives before their cancer diagnosis [5]. In other forms of cancer treatment, such as radiation and chemotherapy, similar results are observed.

With the IV in her arm and a pillow propped against her back, Stacy closes her eyes. She feels the gurney’s wheels rolling through the hospital’s halls until suddenly, it stops. The air feels just as cold as it did in the doctor’s office when she got her diagnosis almost a week ago. Slowly, she opens an eyelid, and five doctors covered head-to-toe in sterile, blue scrubs and gloves appear. A month ago, she was picking out colors for the nursery, and now she’s in an operating room to remove tumors that riddle her lungs. The doctors whisper reassuring words, but they are masked by the anesthesia creeping into her system. The next time she wakes, Stacy feels a dull, lulling pain on her side, stretching between her ribs. Bed-bound and silent, she closes her eyes, hoping the affliction will subside on its own.

In pregnant cancer patients, like Stacy, some treatments are suddenly not options. Exposure to radiation during the first trimester of pregnancy can cause the fetus to have mutations or experience harm to neurological and physiological development [4]. In addition, chemotherapy is generally unsafe for the fetus in the first trimester of pregnancy but considered a stable option for pregnant women in the second or third trimester of their pregnancy [1]. Surgeries in cancer treatment are primarily used to resect tumors that doctors have already detected or to explore the body for any new metastasized cells. Although surgery with general anesthesia is considered a safe option for pregnant women, exploratory procedures are limited due to the negative effects that a prolonged time under anesthesia can have on a patient and her baby [3]. This limits the ability of physicians to develop a fully extensive treatment plan in order to protect the fetus. For all patients, cancer treatment will be different. Depending on factors, such as underlying health conditions, pregnancy, age, sex, and more, certain therapies will be more viable options than others. Physicians must consider a series of decisions to develop treatment plans and the measures they can take when attempting to save their patients’ lives [2]. It is not a standardized protocol.

Three days after her operation, Stacy sits up in bed, cup full of ice chips in hand and IV stuck in her vein. She can feel the insomnia starting to catch up to her, yet she cannot even close her eyes without her mind overflowing with anxious concerns for her own wellbeing and her baby’s health. At her side, her husband rests his hand on her shoulder, eyes full of hope and eagerness. In front of her, a team of twelve doctors, arms full with her chart and scans, stand with a different look in their eyes. “Stacy, we were able to successfully remove the tumors on your right lung. However, as we were closing, we noticed some swelling in your lymph nodes. We ran some tests and it appears that cancerous cells have further metastasized. Since you are just entering your third trimester, we will prepare you for multiple rounds of chemotherapy.” The news, although expected, is still shocking. Stacy’s mind reverts back to the idea of the smell of the fresh paint in her baby’s nursery. She feels her husband’s tears drop on her arm, but when she looks up at him, he hides them. Was it worth hearing the news? Would it have been better to live in the three-day post-op period of bliss where she thought the hard part of the battle was over? As the other doctors begin to clear out and her husband follows them with a longer list of questions than before, Stacy whispers to her oncologist, “I’m going to fight this. I want to make it through for him and for my baby girl. But, if it comes down to me or the baby, choose her. Please save her.”

Communication between physicians and patients is imperative when deciding the course of treatment. Dr. Wendy Baer, an active psychiatric oncologist from the Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University, explained the importance of knowing a patient first-hand. As she recounts her experience, Dr. Baer wears a reassuring smile. “Throughout the years, I found that helping cancer survivors is not about whether they feel better because that can change from day to day. Rather, it’s how they feel about their place in life and the reality of their disease. Although cancer is daunting, most people have some sort of motivation to propel them through the rigorous treatments. I find that through conversations with my patients and use that to guide them.” Dr. Baer emphasizes one of the hardest points to come to terms with when receiving a cancer diagnosis: reality. Often for a patient, it is difficult to grasp the diagnosis, but it is extremely important that they realize how fast their lives may change due to treatments and tests. This stage in mental health for a patient can be eased. “I also talk to their family and friends—their support system—with and without the patient to ensure that not only the patient has adequate support to push them through their battle but also that their support system can remain strong and steady. This is why each minute, each conversation, and each meeting is extremely vital to the way I treat my patients.” The communication between a patient, their family, and the physician can change each step in the treatment process.

Stacy maintains eye contact with her doctor. “Please save her. She has a whole life to live.” The doctor nods as she understands what her patient is asking for. “Stacy, there’s a new clinical trial for metastatic Non-small Cell Lung Carcinoma patients. I don’t know if this will work, but it will give you at least a better chance for you to get through this. I know what you’re asking me to do, choosing the baby over you, but Stacy, this is an opportunity for both of you to get through this. Your baby girl needs her mother. Fight for her.”

Introducing novel treatment research into clinical applications is risky. In the context of cancer, novel treatments refer to new methods of cancer therapies that are being implemented in cancer patients’ regiments. These are developed in laboratories and then tested in clinical trials to see their ultimate efficacy rates compared to already existing treatments on potential adverse effects on patients. In an interview with Lauren Hong, a current biomedical engineering student at the Georgia Institute of Technology conducting cancer research at the Haynes Lab of Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering, she discussed implications of novel treatments from a researcher’s perspective: “When developing a method to cure a disease such as cancer, researchers tend to look at whether cancer growth can be minimized and terminated cell by cell. However, in clinical trials, psychological symptoms may be observed and recorded as adverse effects of the treatment. In addition, in order to be accepted into a clinical trial, a lot of researchers screen patients’ mental health to establish whether they are stable enough to endure the pressures of novel treatments.” Although these novel treatments can provide a curative method to cancers, there can be significant mental adverse side effects that researchers fail to consider initially. This can have a detrimental impact on the patient’s recovery, which causes people to question whether it is ethical to allow patients who are prone to negative mental health symptoms and disorders, such as depression, to participate in novel treatments, even if it will cure their cancer.

Two months into endless rounds of chemotherapy burning through her veins, hair falling out, swallowing painkillers on a dry throat, and undergoing extra experimental procedures for the clinical trial, Stacy is losing hope. Her face is gaunt. A couple of weeks ago, with her husband’s help, she completely shaved her head. The clinical trial, once full of hope and promise, did not appear to have a significant impact on the mets growing in her body. She trudges out of bed every morning into a wheelchair only to get stuck with needles for one reason: her baby on the way. Was this clinical trial even worth the extra pain? What was it doing besides draining her remaining energy and will to keep pushing through treatment only to not work?

“Stacy, we received your latest scans. It appears that your cancer has now metastasized to your brain, bones, and bloodstream. Your body has not responded to chemotherapy at the rate we wanted it to, and given your condition, there is not much we can do that won’t hurt you further. I’m sorry, but you have a few months left to live.” Stacy stares blankly at her doctor. She cannot smell the fresh layers of pink paint anymore. All she can sense are her husband’s tears falling on her arm and the faint sound of the IV drip.

When there is nothing to be done and death is suddenly a harsh reality, where do we turn? Do we blame the physicians or our own body for failing us, or do we accept the inevitable? The concept of our mortality dangles in front of our faces from the moment we are born, yet the idea of dying is, to put it bluntly, daunting. With intensive treatments for aggressive and terminal diseases such as cancer, a patient makes sacrifices to both their physical and mental health in order to survive. At what point do we cross the line of being afraid of death and being okay with it? With a deep breath and a somber look on her face, Dr. Baer talked about how she discusses death with her patients. “It’s hard to bring up the concept of death with terminally-ill patients, much less the blunt reality of it. I try to ease my patients into the reality of their mortality from the very beginning of treatment, and it’s important that their support system is there for them during this transition, but that’s also difficult because the patient’s death will impact them drastically as well. There’s no one right way to talk about death, but having your people there makes it easier.”

A few weeks after the news of her deteriorating condition, Stacy holds her healthy baby girl, Ella, in her arms. Her breath is labored, but tears of joy cover her face. Her husband kisses her forehead and takes Ella into his arms. Ella holds onto Stacy’s finger, as if she knows what is about to happen. Stacy’s last view before she closes her eyes is her beautiful baby’s smile. With her last inhale, she finally can smell that light pink paint again.

Final Note: Decisions in medicine are not black and white. There is never one specific way to treat a patient, especially in oncology. The choices both the physician and the patient make can tread the line of whether it is beneficial or not. Even though Stacy is a fictional character, people in real life experience similar dilemmas as hers. The reality of cancer and dying creates situations where these patients, their families, and physicians have to choose the best decision for their own circumstances.

References

[1]Esposito, S., Tenconi, R., Preti, V., Groppali, E., & Principi, N. (2016). Chemotherapy against cancer during pregnancy: A systematic review on neonatal outcomes. Medicine, 95(38), e4899. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000004899

[2]Ghose, S., Radhakrishnan, V., & Bhattacharya, S. (2019, March 28). Ethics of cancer care: Beyond biology and medicine. Retrieved October 15, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6467456/

[3]Hepner, A., Negrini, D., Hase, E. A., Exman, P., Testa, L., Trinconi, A. F., Filassi, J. R., Francisco, R., Zugaib, M., O’Connor, T. L., & Martin, M. G. (2019). Cancer During Pregnancy: The Oncologist Overview. World journal of oncology, 10(1), 28–34. https://doi.org/10.14740/wjon1177

[4]Radiation and Pregnancy: A Fact Sheet for the Public. (2011). Retrieved from https://emergency.cdc.gov/radiation/pdf/prenatal.pdf

[5]Schwartz, R. M., Yip, R., Flores, R. M., Olkin, I., Taioli, E., & Henschke, C. (2016). The impact of resection method and patient factors on quality of life among stage IA non-small cell lung cancer surgical patients. Journal of Surgical Oncology, 115(2), 173-180. doi:10.1002/jso.24478

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank Dr. Holly Gallagher for providing me the means to creatively explore complex scientific concepts and start conversations on bridging the gap between medicine and communication. I would also like to express my gratitude for my family, who always encourage me to delve into my surroundings and learn as much as I can.