Peer Pressure:

Physical and Cultural Changes Under Self-Domestication

by Naiomi Cookson, Anthropology

As a species, humans have undergone the process of self-domestication: a process in which a species sexually selects for traits that reduce outward, reactive aggression within the population. There is limited information to point to a catalyst that may have begun this species-wide change. An undertaking of this magnitude typically occurs in species that place a higher reliance upon community connections, social aid, and altruism. These populations select against reactive aggression because there is a benefit to active members of the community who receive aid for their good deeds. There are physical characteristics that are associated with domesticated animals and the possession of these traits is referred to as domestication syndrome. These traits occur in the human fossil record in concentrations that support the concept of self-domestication in the human lineage. By observing when specific traits appear, the traits which push for self-domestication can be identified. Though there are many hypotheses surrounding this, it is generally a challenge to identify evidence in the fossil record as many cultural traits do not preserve. One of the more probable and well-supported theories is that our predisposition to language is closely related to the catalyst of the Homo sapiens self-domestication journey. An increased complexity in communication allowed for more sophisticated discussion to take place, introducing the option for premeditated actions and intricate social organization.

self-domestication, sexual selection, cranial morphology, aggression

Domesticated animals are some of the first that children learn about as they grow up. Cows and sheep, dogs and cats, these are animals that have undergone the process of domestication and become commonplace to the average person. But what makes these animals different from their wild counterparts? How do Homo sapiens compare to these domesticated creatures? Some theorize that humans have undergone a process of self-domestication. Understanding how humans went through this process and what the catalyst was that would set the human story into motion are integral to the discernment of how H. sapiens differ from our hominin ancestors and why we were successful where the others failed. By looking at morphological changes in skeletal anatomy, the development of the brain, and shifting values in social pressures there is an opportunity to determine when humans may have undergone self-domestication and why they were pushed to do so.

The origin of human self-domestication is a topic that is up for debate in the anthropological community. Researchers are presented with a chicken-or-the-egg style question: did self-domestication cause the physical, societal, and linguistic changes that occurred, or were any combination of these traits the impetus that resulted in a domesticated member of the genus Homo?

Domestication is considered to be “the process by which humans transformed wild animals and plants into more useful products through control of their breeding” (Leach, 2003, p. 349). If domestication requires human intervention, how can humans be self-domesticated? Self-domestication is the idea that a species breeds in order to reduce the overall aggression present. This is a noted occurrence in animals like dogs and cats. Through their interactions with humans, they receive some benefit and thus sexually select for less aggressive traits. Within some other primate communities, like bonobos, this is also observed but as a reaction to community pressures and as a method of conflict resolution (Wrangham, 2019). The determination of domesticity is drawn from a mixture of features called the domestication syndrome, which are phenotypic alterations in appearance, behavior, and anatomy that occur in most domesticated mammals (Wrangham, 2019). As species move away from their more aggressive behaviors, there is an observable reduction of body size, trend towards feminization, and decrease in sexually dimorphic traits.

Wrangham (2019) determines there are two types of aggressive behavior which distinguish between domesticated and undomesticated species. Reactive or impulsive aggression is an immediate, instinctual turn to violence when threatened or challenged (Wrangham, 2019). This is the aggression that is selected against in the domestication process. The other form of aggression is proactive or premeditated, which is aggression that has been thought out, the consequences considered, and a plan formed (Wrangham, 2019). This can be thought of in terms of planning to overthrow a leader or the use of capital punishment in retaliation for wrongdoing. This is the ‘goal’ aggression, and it should be used in a limited fashion but typically requires the cooperation of multiple parties to fight back against a more powerful rival. The implementation of proactive aggression is a significant development, as it requires forethought and communication between individuals. Cooperation towards a common goal that requires planning and organization of time and coordination, like overthrowing a dominant party, allows for the opportunity of less dominant individuals to gain the upper hand.

Changes in Human Skull and Brain Morphology

Although there is little debate on whether humans are self-domesticated or not (the literature agrees that Homo sapiens are) the questions of what the catalyst for the change was and when it occurred in the evolutionary timeline are thoroughly debated. One theory, supported by Wrangham (2019), is that it occurred shortly before H. sapiens appeared, around 300,000 years ago. This is supported by the archaeological record. There are four main features that archaeologists use to identify species with domestication syndrome, “…reduction in body mass, shortening of the face accompanied by a reduction in tooth size, reduced sexual dimorphism due to feminization, and a reduction in cranial capacity” (Wrangham, 2019, p. 2).

One of the most defining features of what it means to be human is the power, functionality, and social ability of the brain. At a cranial capacity of approximately 1450cc, the brain size relative to “body size is nearly six times bigger than other placental mammals” (Tarlach, 2019). Though the brain has decreased in size slightly since the advent of H. sapiens, it is still larger than most of the archaic hominins in the evolutionary lineage (Wrangham, 2019). The brain does not fossilize which makes determining changes in cranial capacity more complex but not impossible. The size, shape, and endocranial markings on the braincase of the skull allows for considerable information to be understood of the size, shape, and organization of the brain it held (Ponce de Leon et al., 2021).

Regions of the Brain

The brains of H. sapiens share their segments with the brains of other primates, specifically other hominids. They differ, however, in the size of certain segments, organization of the sections, and, of course, overall proportional brain size. The biggest portion of the brain that has seen reorganization compared to great apes are those linked with cortical association. These areas support “higher cognitive function, such as toolmaking and language capabilities” (Ponce de Leon et al., 2021). An idea discussed by Wrangham (2019) is the proposal of self-control being the catalyst for self-domestication because brain size tends to connect with a capability to control responses, and this could facilitate an opportunity to select for less aggressive behaviors. He concludes that self-control is unlikely to be the catalyst, but does not deny that it may have aided in the continuation of the self-domestication process.

The hippocampus and endocranial regions of the brain both have crucial roles in the construction of language. They are also some of the portions that differ most between H. sapiens and great apes with the hippocampus being about 50% larger by volume than those predicted for a hominid of human proportions (Benítez-Burraco, 2021; Ponce de Leon et al., 2021). The hippocampus is particularly unique in its support of language development because it allows for “mental time travel” which is the cerebral movement through time using “episodic memory” (Benítez-Burraco, 2021). The growth of the hippocampus is linked to the evolutionary history of H. sapiens, specifically the self-domestication process, because it allows for increased processing of semantic information. The ability to connect disjointed information together to form complex conclusions would be necessary for a population that selected against aggressive traits, leading them towards a community based on cooperation and complex social networks (Benítez-Burraco, 2021).

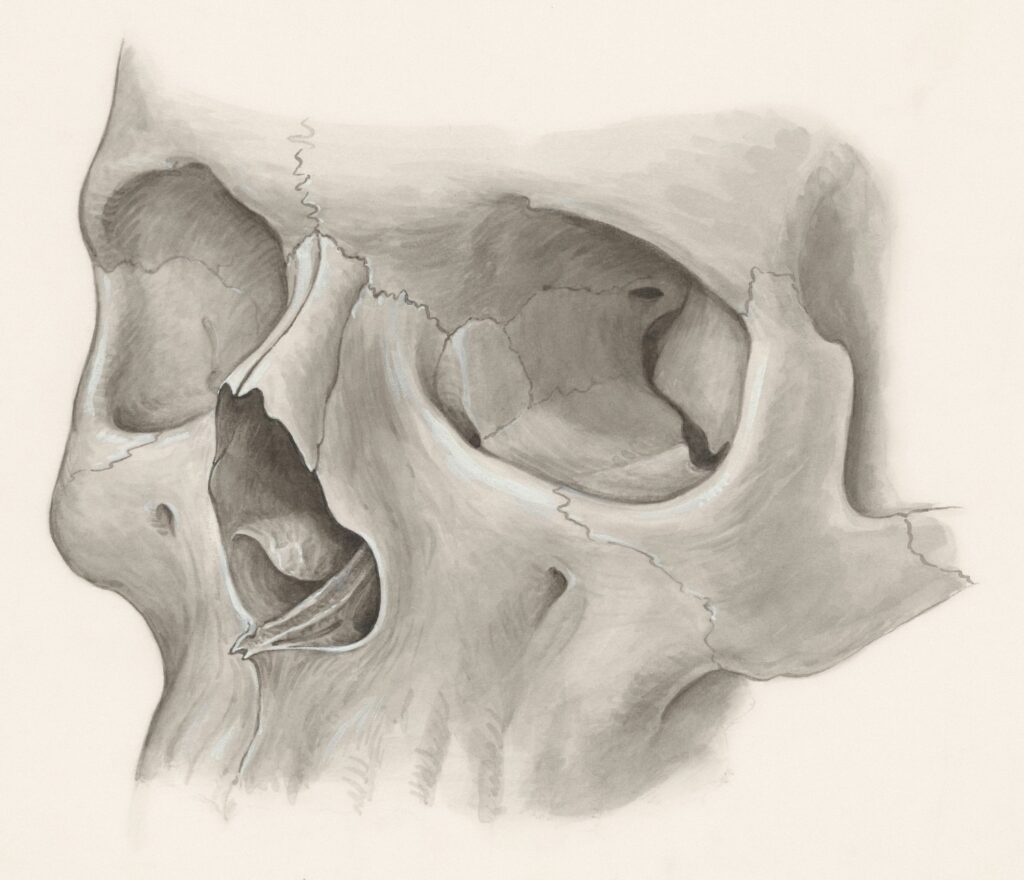

Alterations to the Skull

Due to the brain development and organizational changes between hominin species, there is variability in the brain case of the skull based on species (Ponce de Leon et al., 2021). H. sapiens have a brain organization that encourages modern cognition and sophisticated language, which has resulted in the skull undergoing a globularization process. The skulls of H. sapiens are considerably rounder and more globe-like than those of ancient hominins, and it has become a telling feature of the species (Benítez-Burraco et al., 2016). As noted in the works by Benítez-Burraco and colleagues, this globular characteristic of the skull is associated with language production, which relates to the self-domestication process undergone by the species. This morphological change seems to expand beyond the effect of language.

The skull is altered by the domestication syndrome traits. As H. sapiens became domesticated, the skull lost the prognathic features of the lower face, caused in part by the reduction in the robusticity of teeth from use of fire to cook foods (Wrangham, 2019). Other outside influences may have altered the skull through brain organization. This organization model optimizes for language, but it also can alter based on cultural processes and expectations (Benítez-Burraco et al., 2016). There seems to be a reciprocal relationship between cranial capabilities and self-domestication. In order for self-domestication to begin, certain standards had to be met, based on Wrangham’s (2019) argument, language was one of these, if not the main criterion, as it introduced the opportunity for increasingly intricate social orders. However, for the brain to organize into an appropriate neural scaffolding able to support sophisticated language and complex social systems, self-domestication needed to have already begun.

Culture and Social Pressures

Many of the ideas attempting to identify the catalyst for self-domestication proposed in Wrangham’s (2019) paper are associated with social organization. In his work Hypotheses for the Evolution of Reduced Reactive Aggression in the Context of Human Self-Domestication, Wrangham (2019) recognizes the nine leading ideas attempting to explain self-domestication: genetic group selection, group-structured culture selection, social selection by female mate choice, social selection by choice of cooperative task partners, self-control, cooperative breeding, population density, use of lethal weapons, and language-based conspiracy. They are all what he refers to as indirect explanations, meaning they are “designed to explain why cooperation had been favored rather than aggressiveness being reduced” (Wrangham, 2019, p. 2). The indirect explanations use the social pressures that may exist within a given population to explain a selection for docility. Genetic group selection is based around the ideas of parochial altruism (Wrangham, 2019). That is to say, if you exist within an individual’s genetic group, you are likely to be on the receiving end of their altruistic behaviors, which is inherently beneficial.

If a high propensity is placed on giving and receiving these behaviors, aggressive traits will inherently be chosen against. Group-structured cultural selection is in a similar vein but with less of a focus on genetic altruism and an increased focus on the spread of social behaviors over generations (Wrangham, 2019). Both of these ideas run into the problem of focusing too much on continuation of cultural traits within a population and disregarding the limited effect of aggressive behavior on these topics. Social selection covers the remaining two methods of indirect explanation (Wrangham, 2019).

Sexual Selection and Mate Choice

When reproducing, females tend to be more selective due to the physical cost and time investment that affects them during gestation. Females, therefore, have some power in terms of selecting sexual partners by leaning away from certain gene frequencies, in this case more aggressive males. The other form of social selection is through the choice of “cooperative task partners,” a term describing a partner who helps with daily costs and chores like hunting and foraging, warfare, and care for the young (Wrangham, 2019). Like genetic group selection, there is a hope of promoting an altruistic culture within the population through interdependence and dissuading from more aggressive behaviors. The problem the social selection hypothesis runs into is the assumption that the aggressive males who are being selected against, who are typically of high status, can use their power and physical dominance to remove female choice from the equation and ensure reproduction (Wrangham, 2019).

Each of the indirect proposals presented have a significant problem with not properly considering the power that aggressive traits have over a population. They ignore the existence of similar scenarios in modern day primates, like chimpanzees, that are not self-domesticated and seem to be making no move in that direction (Wrangham, 2019). There is a final indirect explanation regarding self-control mentioned earlier in the paper. The self-control idea stems from the idea that increased brain size would encourage individuals to choose to be less aggressive (Wrangham, 2019). In some situations, it may be beneficial to be aggressive, so having the choice does not mean the less aggressive option will automatically be picked.

Altruism and Social Changes

While the indirect explanations presented by Wrangham (2019) may not be entirely reasonable solutions to what may have jump-started human self-domestication, they still may have some value when considered as methods that kept the process in motion. Moral codes and altruism play a role in every human culture. At the base, H. sapiens are social creatures and rely upon other members of their population for support and aid. Though it may not have had the standing to begin self-domestication, altruism plays a role, to some degree, in between any two individuals with a relationship. The definition of altruism is a fickle understanding that alters between “being genetically generous to anybody at all, including kin” and “being generous to people lacking any blood ties to the generous party” (Boehm, 2012, p. 9).

Existing in any human society means feeding into the altruistic behavior that keeps the social system running smoothly. This is an apparent trait in multiple forms of cultural organizations like chiefdoms, bands, and tribes (Boehm, 2012, p. 49). Being altruistic is physically and mentally beneficial for everyone in a social system and is encouraged through the tantalizing potential for reciprocated altruistic behaviors. Under that idea, the cost of altruistic behavior is mitigated as there is a promise of benefiting from the actions of another in the future, thus there are no ‘special costs’ (Boehm, 2012, p. 61). Boehm, in his book Moral Origins: The Evolution of Virtue, Altruism, and Shame, discusses the idea of a “punitive type of social selection” having an impact on the genetic makeup of H. sapiens. He proposes this as a possible lens through which the interactions within modern day foraging groups can be analyzed (2012, p. 75). The continued ability to observe altruistic behaviors in human social groups implicates how relevant the need for such actions is to the continued success of the species.

Conclusion

Humans began domestication of plants and animals around 11,500 years ago with the domestication of the dog. Domestication has seen a shift in understanding in recent years and has been redefined under three methods: animal domestication in the absence of deliberate human selection, attraction to human niches, and gene flow (Larson & Fuller, 2014, p. 116). Under analysis, domestication can be broken down into a few different stages, and the types of domestication are variable depending on the species being domesticated, the group that is domesticating, and the region in which this is all happening (Larson & Fuller, 2014). This breakdown does not occur when looking at the human self-domestication process. Some of the criteria may be irrelevant, like what species is being domesticated, but depending on group and region, there could be some variability in how the self-domestication process played out. The stages of human self-domestication are not something that is apparent within the existing literature.

It was not within the scope of this paper to look at what could be added to the literature, but questions did arise during research. The evolutionary journey from early primates to anatomically modern humans has been a long trial that has seen many drastic changes. At their origins, primates used to be prey animals, but sometime during their evolution, some began to enter into the predator category, one of those groups being H. sapiens. The various populations of H. sapiens went on to domesticate other species of plants and animals for their own benefit but not until much later, well after human self-domestication had begun. An important addition to the literature surrounding domestication and self-domestication would be an investigation into the domestication process from the perspective of the domesticate. Would domesticated humans, who presented with the domestication syndrome traits that implied less aggressive behavior appear less threatening to other animals? Would this increasingly docile appearance encourage other animals to be less afraid of humans and feel more comfortable in their proximity, allowing for an easier transition into domesticity? Larson and Fuller (2014) mentioned in The Evolution of Animal Domestication the idea of domestication occurring due to animal attraction to human niches. Human niche development requires human evolution, which is inherently tied to human self-domestication. This could have played a role in why H. sapiens appealed to other animals and were able to remain close enough to exert a force on their evolution.

Humans have a capacity for complex language, cultural organization, and social structure. There are cultural expectations that enforce certain actions to be prescribed to, like the adoption and enactment of a moral code and altruistic behaviors to benefit surrounding parties. This is supported by a natural inclination to garner favor with others through good actions. H. sapiens have experienced morphological change from brain development and organization, and the domestication syndrome traits that are seen in the majority of domesticated mammals. These features of contemporary humans can provide insight into what beneficial traits could be considered for starting the self-domestication process. Determining if a singular trait is the catalyst is a harder task.

Wrangham (2019) provided insightful analysis of the major proposals surrounding the origins of human self-domestication. He determined the language-based conspiracy held the most detailed support, as it considered selectively breeding against reactive aggression using proactive aggression. Language would allow less aggressive members of a group to premeditate social upheaval and punishments for reactively aggressive individuals. This would account for the reduction of aggressive individuals ensuring fitness through bullying and forced propagation. This theory has the most substantial case to support the catalyst of self-domestication, but the other arguments presented would have kept the process in motion and were instrumental in following the process through to the degree of present-day H. sapiens.

References

Bellwood, P. (2022). The Five-Million-Year Odyssey : The Human Journey from Ape to Agriculture. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691236339

Benítez-Burraco, A. (2021). Mental time travel, language evolution, and human self-domestication. Cognitive Processing, 22(2), 363–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10339-020-01005-2

Benítez-Burraco, A., Theofanopoulou, C., & Boeckx, C. (2018). Globularization and domestication. Topoi: An International Review of Philosophy, 37(2), 265–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-016-9399-7

Bingham, P. M. (2000, January 1). Human evolution and human history: A complete theory. Evolutionary Anthropology, 9(6), 248–257.

Boehm, C. (2012). Moral origins: The evolution of virtue, altruism, and shame. Basic Books.

Corbey, R., & Lanjouw, A. (2013). The politics of species: Reshaping our relationships with other animals. Cambridge University Press.

Hart, D., & Sussman, R. W. (2009). Man the hunted: Primates, predators, and human evolution (Expanded ed.). Westview Press.

Larson, G., & Fuller, D. Q. (2014). The evolution of animal domestication. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 45, 115–136.

Leach, H. (2003). Human domestication reconsidered 1. Current Anthropology, 44(3), 349–368. https://doi.org/10.1086/368119

Ponce de Leon, M. S., Bienvenu, T., Marom, A., Engel, S., Tafforeau, P., Alatorre Warren, J. L., Lordkipanidze, D., Kurniawan, I., Murti, D. B., Suriyanto, R. A., Koesbardiati, T., & Zollikofer, C. P. E. (2021). The primitive brain of early Homo. Science, 372(6538), 165–171. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaz0032

Sánchez-Villagra, M. (2022). The process of animal domestication. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691217680

Tarlach, G. (2019). Finding human ancestors in new places. Discover Magazine. https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/state-of-science-finding-human-ancestors-in-new-places

Wrangham, R. W. (2019). Hypotheses for the evolution of reduced reactive aggression in the context of human self-domestication. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01914

Acknowledgements: Thank you to Dr. Emily Hammerl for all that I learned in your courses and your continued encouragement of my interest in such vast topics. I appreciate all of the guidance and input I have received under your tutelage.

Citation Style: APA