Ethel Smyth’s Influence on the Women’s Suffrage Movement

by Keelin Walsh

Ethel Smyth was a music composer and an active member of the Women’s Social and Political Union, founded to fight against the oppression of women. Her path to success was burdened not only by patriarchal supremacy but also by societal disapproval of her non-conforming appearance and personal relationships. She composed music under the male pseudonym E.M. Smyth in hopes of being noticed for her work. Despite her struggle, Smyth managed to produce six operas, a concert mass, a double concerto, a choral symphony, songs with piano and orchestral accompaniment, organ pieces, and chamber music. Her piece, The March of the Women, though simple in structure, became the anthem for the women’s suffrage movement because of its accessibility and inspiring lyrics. It is composed of a simple melody with four verses, and since its publication in 1911, it has been arranged for solo voice, choir, wind band, brass, a cappella or accompanied by orchestra, piano, percussion, or chamber ensemble. Through my analysis of Smyth’s piece, The March of the Women, I reveal the musical influence she had on the women’s suffrage movement. The recognition she deserves came long after her death, but it is important to continue to shed light on the impacts she made.

Ethel Smyth, suffragette, patriarchy, sexuality, musical compositions

The last two decades of the nineteenth century marked a turning point in the extent and nature of women’s activity in society. The Women’s Social and Political Union was founded in 1903, and suffrage leaders needed resilient and unyielding role models that would inspire women to confront and dismantle society’s patriarchal supremacy. Ethel Smyth fearlessly forged a career for herself as a professional composer in Britain during a time when female musicians were regarded as inferior to male musicians.[1] When analyzed, her piece, The March of the Women, as well as the social impact of Smyth’s sexual orientation, reveal her influence on the women’s suffrage movement.

Early Life

Ethel Smyth was born into a prosperous military family in Sidcup, England, near London.[2] Her father believed a woman’s role in music should be limited to performing in operas or playing piano for household entertainment, and that they would rarely become composers. Despite her father’s discouragement, Smyth quickly excelled at the piano and even composed her first hymn by age ten.[3] At age twelve, she heard a piece composed by a governess and was inspired to study music. After much dispute with her father, Smyth traveled at age nineteen to Germany, where she studied at the Leipzig Conservatory. There she discovered the musical influences of Antonín Dvořák, Clara Schumann, and especially Johannes Brahms, whose music left a permanent stamp on her own. Smyth worked hard to achieve the recognition and attention her works deserved, which resulted in numerous published compositions and arrangements, including six operas, a concert mass, a double concerto, a choral symphony, songs with piano and orchestral accompaniment, organ pieces, and chamber music.[4]

Impact of Sexuality on Career

Smyth was determined to continue fighting against the societal biases women faced as she began her career as a composer. Smyth’s earliest work to receive a public hearing was Sonata in A Minor, Op. 7 for violin and piano. However, critics felt the piece was “devoid of feminine charm and therefore unworthy of a woman.”[5] Trying to succeed as a composer who specialized in opera and large-scale symphonic/choral works, Ethel Smyth was a prime target for critics in regard to sexual aesthetics.[6] Smyth’s four-movement Serenade earned her first orchestral debut and first public debut in her native country, but she decided to try to avoid biased criticism by using the name E. M. Smyth.[7] This facade was reflected in the compositions themselves as well as in her physical appearance, both described as containing masculine energy.

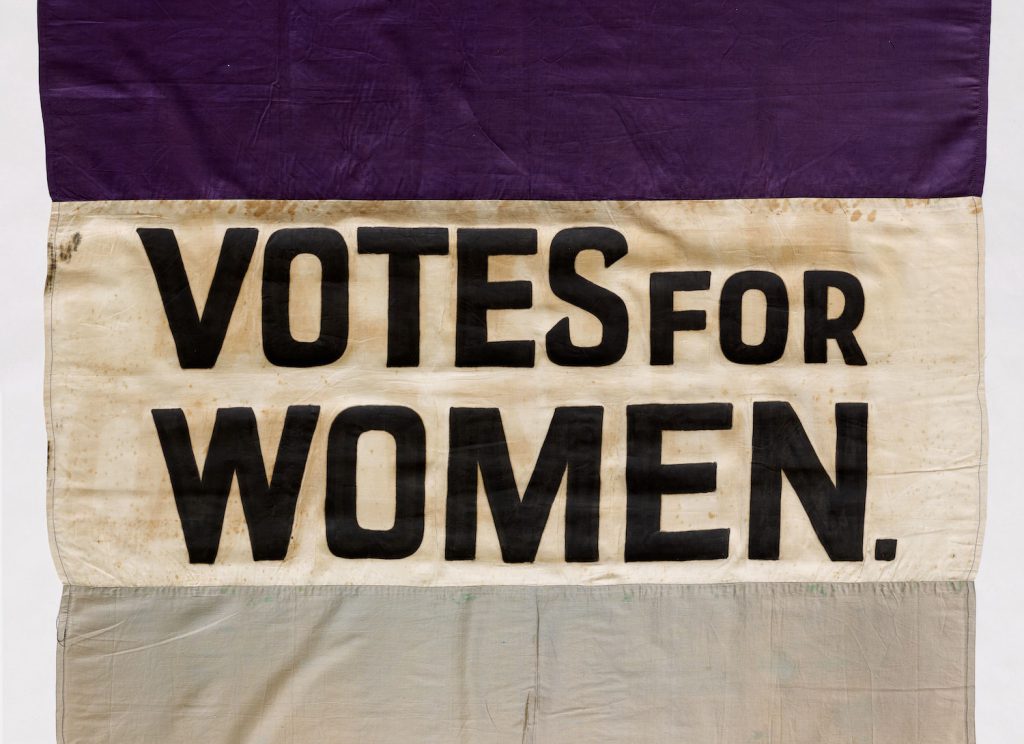

Individualized to the last point, she had in middle age little about her that was feminine. Her features were clean cut and well marked, neither manly nor womanly; her thin hair drawn plainly aside, her speech clear in articulation and incisive rather than melodious, with a racy wit. Wearing a small mannish hat, battered and old, plain-cut country clothes…she would don a tie of the brightest purple, white, and green, or some hideous purple cotton jacket or other oddity in the W.S.P.U. colours she was so proud of, which shone out from her incongruously like a new gate to old palings.[8]

quoted in p. 129, originally from The Suffrage Movement, quoted by St. John, 153-54).

It is clear that Smyth received unnecessary criticism simply based on her stereotypical “masculine” appearance. The independence that sexual freedom unveiled was crucial to the establishment of feminism. All men, even gay men, reaped the benefits of patriarchal supremacy and these men were the ones trying to decide what physical characteristics women needed to be considered “feminine.”[9]

Smyth’s personal life has endured much controversy over the years. Her closest community and chief comrades were women artists, writers, musicians, activists, and wealthy sponsors, leading to the speculation that she was queer.[10] In one of her memoirs, Smyth describes her romantic feelings for the women in her life, saying she “drew up a list of over a hundred girls and women to whom, had [she] been a man, [she] should have proposed.”[11] Sexual identity was difficult to label in this time period because of societal norms and lack of terminology used to describe nonconforming relationships.

As Smyth’s reputation grew worse with music critics, it flourished in the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). She failed to rise to fame under the pseudonym E. M. Smyth. Instead, she decided to compose works other than piano music and art songs, to which women had seemed to confine themselves. She composed a German opera titled Der Wald, which became the first opera by a woman to be performed at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York, enabling her to break out in a field dominated by male composers.[12] This drew the attention of suffragettes and a woman named Emmeline Pankhurst reached out to Smyth and invited her to join the WSPU. After her historical debut, Smyth focused on having her works performed in prestigious opera houses, so she refused the offer to work with the WSPU.[13] However, it only took a few letters back and forth between Smyth and Pankhurst to convince her to join. On September 15, 1910, Smyth pledged to the WSPU’s Votes for Women Campaign.

Smyth was quickly infused with the desire to be a voice in the women’s suffrage movement. Her struggle to become acknowledged in the music world as herself and not under a pseudonym reflected the issues women faced within society. Like other defiant artists who stand on the cutting edge of the larger culture, to sustain identity and to protect her work Smyth ran the risks of censorship and misunderstanding, even from those who shared the stigma of the sexual outsider.[14] In her memoirs, Smyth argued that women’s disadvantages in music stemmed from their lack of political voice or vote and from the absence of strong British musical traditions that might nourish them.[15] Smyth believed she could aid in the fight to dismantle these hindrances and composed a song that encouraged the empowerment of women. She used words by Cicely Hamilton in composing The March of the Women.[16] She used the text to inspire women to stand strong together and fight for a new future, free from patriarchal rule. The words transformed this work into a symbol of tenderness, hope, faith, and the cheerful and triumphant thrill of victory.[17]

Musical Analysis

This composition is not known for its complexity, but rather its accessibility. Its purpose was for women of every musical background to unite their voices against the oppression they faced. The original sheet music of The March of the Women copyrighted in 1911 is a very simple version of what is often heard today.[18] Smyth wrote this piece in F major and in common time (4/4), which is a fairly standard meter for marches. The overall form of the work is strophic because of its many verses that use the same melody. There is a shift in tonality within each individual verse. The opening melody stays in the home key of F major and then modulates to the dominant before returning to F major. Some singers, loyal to a more familiar derivative, the “Women’s Marseillaise,” complained that it was hard to sing the middle stretch. This is because the tonality shifts from F major into the dominant C major, thus it raises the voice to a diminished seventh (at the words “call,” “voice,” “pain,” “hope,” in each respective verse) before relenting to the tonic key and recapitulation of the two last lines.[19] Smyth defended this upward intervallic leap as “peculiarly British,” and it was her technique of opening up the voice to create more resonance.[20] The final measure has a slight change in rhythm from the original four quarter notes to two options depending on the text: quarter, quarter, half, or quarter, dotted eighth, sixteenth, half. Either way, the final half note creates a moment of resolution that was not provided earlier in the piece.

Smyth prepared multiple editions and arrangements for any and every performance opportunity, site, and vocal resource: whether indoors and out, for solo voice, choir, wind band or brass, a cappella or accompanied by orchestra, piano, percussion, or chamber ensemble.[21] This was an incredibly time consuming process, but it was necessary to reach various musicians and audiences. An interesting yet effective feature of some prints of the sheet music is the written solfège provided above the vocal line. Solfège, or solmization, was invented in eleventh-century Italy by Guido of Arezzo and has been altered and popularized over centuries as the comprehensive way to read the notes of a work.[22] Smyth incorporates solfège to make this piece easy to learn on the spot so everyone can sing along. The melody is haunting and intended to ring in the ears as both a hymn and a battle call.[23]

The Impact of The March of the Women

The first performance of The March of the Women was by a voluntary Suffrage Choir trained and conducted by Smyth. It gained much attention and was quickly launched in a flurry of rehearsals, publicity, previews, and ecstatic reviews.[24] Smyth herself conducted all performances of The March of the Women at occasions ranging from private WSPU meetings to concerts, satirical plays, and large-scale suffrage demonstrations.[25] It is a propaganda song, no less: inexpensive, portable, and pocketable, a multipurpose commodity for the mass market.[26] Lyrics were easily recorded on paper and passed out at rallies and protests. A turning point in Ethel Smyth’s career occurred during a suffrage demonstration. On March 4, 1912, there was an orchestrated window smashing campaign near the West End of London. This was organized in protest of Prime Minister H. H. Asquith’s continued prevarication over granting women the right to vote.[27] That night after police found scraps of paper with lyrics to The March of Women, Smyth was arrested and served a jail sentence for two months. Contrary to popular belief, Smyth most likely felt liberated and even more motivated to continue the cause thanks to support from Sir Thomas Beecham. He was a fellow conductor and confidante of Smyth’s during her opera cycle titled The Wreckers. He visited her in jail and was eager to describe the scene of her conducting The March of the Women with a toothbrush through her cell bars.[28] Her impromptu ensemble was composed of suffragettes who had also been arrested along with prisoners in the jail who could pick up the tune. Beecham shared this event with journalists, which gained Smyth more attention even while in prison.

Smyth’s Lasting Impact

Ethel Smyth’s time in jail inspired her to compose her oratorio and her last large-scale work The Prison. While the challenge she posed throughout her career to the musical patriarchy may have contributed negatively to the reception of her works in her own day, ironically it may be this same resistance to inequality that has led to a proliferation of recent performances of her music. In 2021, Ethel Smyth received a Grammy based on the recording of her work by conductor James Blachly and soloists Sarah Brailey and Dashon Burton, members of Experiential Orchestra. The Prison was released in August 2020, to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment, which gave women the right to vote in the United States. The idea of “the prison” has been interpreted as both an actual jail and a metaphorical one for Smyth. Smyth’s service to the suffragette movement, although comparatively brief, has created a lasting impact that has kept her memory alive in mainstream historical narratives and has recently nurtured substantial interest in her music, as well.[29]

Ethel Smyth’s composing and conducting career came to an end when she developed severe hearing loss. However, this obstacle pushed her to turn to writing and Smyth published a total of ten books and memoirs in the last twenty-five years of her life.[30] Her literary works are wide-ranging and cover a host of different subjects, including recollections about her own life, biographical portraits of close friends, excerpts from letters, reviews of her musical compositions, and her opinions about women’s rights.[31] Smyth’s acknowledgement of her career is clear:

The exact worth of my music will probably not be known until naught

remains of the writer but sexless dots and lines on ruled paper . . . but if

something of the immense savour of life that hope deferred has been powerless

to mar; if the sense of freedom, detachment, and serenity that floods the heart

when, suddenly, mysteriously, the wretched backwater of a personal fate is

swept out of the shallows and becomes part of the main current of human

experience; if even a modicum of all this gets into an artist’s work, that work

was worth doing. And should the ears of others, whether now or after my

death, catch a faint echo of some such spirit in my music, then all is well, and more than well.[32]

For her compositions and her fight against sociocultural obstacles, her achievements should be appreciated. Ethel Smyth’s impact on the suffragette movement, both musically and personally, is notable and inspiring. The March of the Women became the official anthem for the Women’s Social and Political Union and is still performed today. The significance of her profoundly feminist politics and the creative depth of her works should stand as a testament to women and their fight for equality over the centuries. While hints of patriarchal supremacy remain present, Ethel Smyth would likely be proud of the fight women have set in motion over the past century and of the positive impact she has had on society’s acceptance of women’s music as well as their pursuit of the sexual relationships they desire.

Bibliography

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “solmization.” Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed April 10, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/art/solmization.

Gates, Eugene. “Damned If You Do and Damned If You Don’t: Sexual Aesthetics and the Music of Dame Ethel Smyth.” Journal of Aesthetic Education 31, no. 1 (1997): 63-71. doi:10.2307/3333472.

Harris, Amanda. “Recomposing Her History: The Memoirs and Diaries of Ethel Smyth.” Life Writing 8 (4): 421–31 (2011). doi:10.1080/14484528.2011.619716.

Lee, Alexander. “The Music of Time No. 11: The Suffragette Songstress: Ethel Smyth Took on the Forces of Inequality, in Both Politics and Culture, Producing Highly Acclaimed Works of Music That Are Now All but Forgotten.” History Today 68, no. 5 (May 2018): 86–88. 28985561&site=eds-live.

Lebiez, Judith. “The Representation of Female Power in Ethel Smyth’s Der Wald (1902).” The German Quarterly 91 (4) (2018): 415–24. doi:10.1111/gequ.12084.

Lumsden, Rachel. 2015. “‘The Music Between Us’: Ethel Smyth, Emmeline Pankhurst, and ‘Possession.’” Feminist Studies 41 (2): 335.

Smyth, Ethel. 1946. “Impressions That Remained.” New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Smyth, Ethel. The March of the Women. The Woman’s Press, 1911.

Wiley, Christopher. 2018. “Ethel Smyth, Suffrage and Surrey: From Frimley Green to Hook Heath, Woking.” Women’s History (2059-0156) 2 (11) (2018): 11–18, accessed March 25, 2021. https://epubs.surrey.ac.uk/849970/.

Wiley, Christopher. “Music and Literature: Ethel Smyth, Virginia Woolf, and ‘The First Woman to Write an Opera.’” Musical Quarterly 96, no. 2 (December 2013): 263–95. doi:10.1093/musqtl/gdt012.

Wiley, Christopher. 2004. “‘When a Woman Speaks the Truth about Her Body’: Ethel Smyth, Virginia Woolf, and the Challenges of Lesbian Auto/Biography.” Music & Letters 85 (3): 388–414, accessed March 25, 2021. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3526233.

Wood, Elizabeth. “Performing Rights: A Sonography of Women’s Suffrage.” The Musical Quarterly 79, no. 4 (1995): 606-43, accessed March 24, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/742378.

Wood, Elizabeth. “Women, Music, and Ethel Smyth: A Pathway in the Politics of Music.” The Massachusetts Review 24, no. 1 (1983): 125-39, accessed March 24, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25089403.

Notes

[1] Rachel Lumsden, “The Music Between Us: Ethel Smyth, Emmeline Pankhurst, and ‘Possession’” in Feminist Studies, (2015), 335.

[2] Eugene Gates, “Damned If You Do and Damned If You Don’t: Sexual Aesthetics and the Music of Dame Ethel Smyth”in Journal of Aesthetic Education, (1997), 64.

[3] Alexander Lee, “The Music of Time No. 11: The Suffragette Songstress: Ethel Smyth Took on the Forces of Inequality, in Both Politics and Culture, Producing Highly Acclaimed Works of Music That Are Now All but Forgotten” in History Today, (2018), 86.

[4] Gates, “Damned If You Do and Damned If You Don’t,”65.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid, 64.

[7] Ibid, 65.

[8] Elizabeth Wood, “Women, Music, and Ethel Smyth: A Pathway in the Politics of Music” in The Massachusetts Review (1983), 128.

[9] Christopher Wiley, “When a Woman Speaks the Truth about Her Body: Ethel Smyth, Virginia Woolf, and the Challenges of Lesbian Auto/Biography”in Music & Letters, (2004), 394.

[10] Wood, “Women, Music, and Ethel Smyth: A Pathway in the Politics of Music,” 129.

[11] Ethel Smyth, “Impressions That Remained,” introduced by Ernest Newman, New York: Alfred A. Knopf (1946), 59.

[12] Judith Lebiez, “The Representation of Female Power in Ethel Smyth’s Der Wald (1902)” in The German Quarterly, (2018), 420.

[13] Ibid, 416.

[14] Wood, “Women, Music, and Ethel Smyth: A Pathway in the Politics of Music,”127.

[15] Ibid, 130.

[16] Elizabeth Wood, “Performing Rights: A Sonography of Women’s Suffrage” in The Musical Quarterly, (1995), 616.

[17] Ibid, 617.

[18] Wood, “Women, Music, and Ethel Smyth: A Pathway in the Politics of Music,”130.

[19] Wood, “Performing Rights: A Sonography of Women’s Suffrage,”619.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid, 617-618.

[22] Britannica Editors, “solmization” in Encyclopedia Britannica, (2022).

[23] Ibid, 617.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Wiley, “Ethel Smyth, Suffrage and Surrey,”10.

[26] Wood, “Performing Rights: A Sonography of Women’s Suffrage,”617-618.

[27] Wiley, “Ethel Smyth, Suffrage and Surrey,” 13.

[28] Wood, “Women, Music, and Ethel Smyth: A Pathway in the Politics of Music,”130.

[29] Wiley, “Ethel Smyth, Suffrage and Surrey,”13.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Lumsden, “The Music Between Us,”336.

[32] Amanda Harris, “Recomposing Her History: The Memoirs and Diaries of Ethel Smyth” in Life Writing, (2011), 77.

Acknowledgements: Thank you to Dr. Joshua Bedford for highlighting underappreciated musical composers and to Mr. Cameron Steuart for encouraging me to submit this paper to be published. A special thank you to my family and friends who support me in every endeavor.

Citation Style: Chicago