Culture through Creation

Exploring the Ancient Mexica through their Mythos

by Alexander “Sasha” Severtson

Because of the lack of objective records and secondary sources from ancient civilizations, extracting a complete image of their cultures requires analysis of the subtext of mythological pieces and other primary sources. The Mexica creation story, Birth and Death of the Fifth Age, is a prime example of such a document. Narratively, it tells how the sun and moon were brought about by the gods but a closer look at the plot, characters, and descriptive details gives readers an image of the culture, society, and moral communities of the Mexica people.

Key Words: mythos, deities, creation, culture

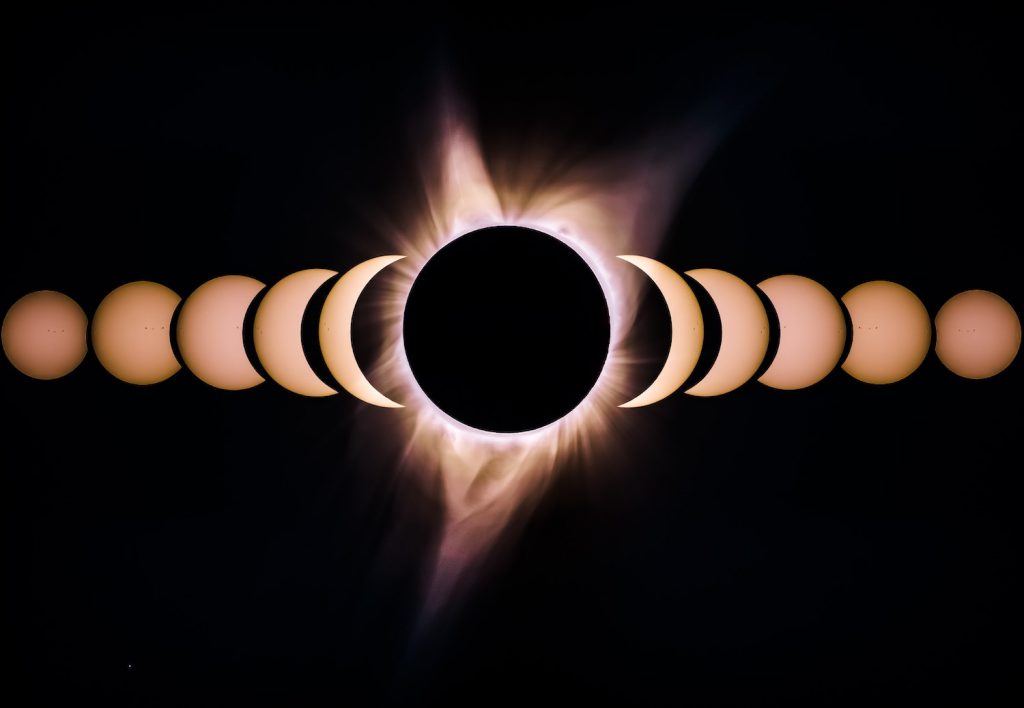

In the absence of fact, fiction often becomes the foundation of reason. Such is the case with Birth and Death of the Fifth Age, a Mexica mythological story about the creation of the sun and moon. The narrative tells of the various sacrifices made by the Mexica gods to bring light into the world. It begins after the awful fourth age, a period marked with darkness and terminated with a deluge and the removal of humans from Earth. To escape this twilight, two gods, Nanauatzin and Tecuciztecatl, are selected to become the sun and the moon, respectively. Their fulfilment of this selection begins with a fast and the two paying great penances; Nanauatzin offers flora and fauna presented with purges from his own body while Tecuciztecatl pays with lavish material goods. Following this, the two championed gods cast themselves in a fire, completing the transition to the celestial bodies. After they make their first appearance in the sky, however, they become stuck. To fix this, the other gods agree to be killed by one of their own, Ehacatl. After a short chase for Xolotl, the one god who feared death, the deities are sacrificed and the sun and moon begin their perpetual motion, bringing about light, life, and the fifth age.

While the surface level of this text plainly provides a creation story, deeper probing reveals the ethos, pathos, and logos that defined the Mexica’s moral community and their relationship with the natural world. These representative ideals can be summarized by three general themes that recur throughout Birth and Death of the Fifth Age: sacrifice out of altruism, the presence of a universal hierarchy, and deep respect for the natural world.

Almost everything that is created or accomplished in the story is done so through some form of willful concession. Be it the penance given by Nanauatzin and Tecuciztecatl, their self-destruction in the teotexcalli fire, or the consensual murder of the other gods by Ehacatl, much is given up by the characters. The story also makes it a point to praise these altruistic actions and condemn their opposites: Nanauatzin & Tecuciztecatl are rewarded with adornments, revered for their deaths, and Xolotl is regarded as a coward. The text’s responses to these actions tell much about sacrifice in Mexica culture; it was seen not as a barbaric ritual but rather a well-respected practice worthy of reward. It even goes beyond this by expressing the necessity of sacrifice with the primary story arch: the gods must first give up much to bring about the sun and the moon, essential sources of life. This sentiment can be seen in historical accounts of various Mexica groups who performed human sacrifice frequently as they believed it kept various natural processes in motion/equilibrium. For example, the Aztecs consistently killed members of their own society as they believed it would keep the weather satisfactory; the subjects in these situations were also revered for their actions rather than looked down upon, pointing to the same positive attitude towards sacrifice present in the story.

Another strong tenet of Mexica culture seen in Birth and Death of the Fifth Age is the concept of a hierarchy in the universe. The text describes several dynamics between beings, environments, and actions in which there is a clear distinction of priority. For example, there could not exist two equally powerful suns, Nanauatzin’s manifestation was brighter and therefore more important than Tecuciztecatl’s. Additionally, one would work during the day, the other at night, another clear declaration of order. Even descriptive details are written with a hierarchal framework: some animals such as fish are described as trite and almost mindless while others like the eagle and ocelot are synonymous with strong character traits. This idea of hierarchy plays a similar role to sacrifice in both the story and Mexica culture- it is an explanation for the operations of the universe. Specifically, it proposes that there is a predetermined balance of power in all aspects of life. This underlying belief speaks to the almost universal human tendency to derive order and organization in the natural world- an effort which has empirically been present in both the arts and sciences across the globe. In Mexica groups, this could be seen in their firm hierarchal social structures: rulers considered representatives of the gods by way of cosmic order governed over several classes of citizens each of which had differing statuses, powers, and rights.

The motivations behind sacrifice and hierarchy (along with many other Mexica ideals divulged in Birth and Death) lie in a reverence for the natural world. The narrative has plentiful references and descriptions of nature, indicating its significant presence in the Mexica culture. One of the clearest instances of this is in the story’s central plot point: the gods are trying to create suns and bring light and therefore life to the world. As in many other cultures, the Mexica associate light/the sun with life as it is one of the principal biological necessities of many organisms and processes making it one of their most respected entities. By having this be the primary driving force of the story, readers understand just how central nature is to the Mexica. Another detail of Birth and Death that reveals the Mexica’s deep-seated relationship with the natural world is the presence that nature itself takes in the story. Unlike the strong presence of humans in other creation stories such as those of the Abrahamic religions, the Mexica make little reference to humankind at the beginning; instead, the earth, animals, and plants predate any humans. The total absence of humans in the tale reveals the Mexica deference towards the natural world, one that is steeped in respect and worship, as it shows that humans are not inherently endowed with the Earth. Such veneration is also present in Mexica culture and practices: their art frequently features animals as symbols of power, strength, or other admirable traits. Additionally, they held great respect for the terrain they inhabited, taking great precaution when working the land and never overextending what they considered a privilege. Many of their sacrifices were also performed as offerings to the natural world as explained earlier.

Birth and Death of the Fifth Age may have been written as a means of explaining the origin and habits of the universe, however, it also attests to the culture, morals, and practices of the Mexica people. Most prominently, altruistic sacrifice, hierarchal relationships, and reverence for the natural world are as prevalent in the myth as they are in historical accounts of the native group.

Still, doing a thorough examination of a text of an ancient culture like this has a great deal more than any intrinsic value. By analyzing the way a particular people were in the past, we can better understand similar present-day groups and even make more accurate predictions about the future. With Birth and Death of the Fifth Age, the narrative reveals various aspects of the Mexica culture and how they developed. With this information, comparisons can be drawn to the current societies of Central America and their own cultures. For example, many of the same tenants of the Mexica culture were passed down through the generations and are still present in modern-day Mexican society. One instance of this is the high esteem for the natural world demonstrated in the prevalence of flora and fauna in contemporary Mexican artistic endeavors such as clothing, sculptures, and painting. The practices and beliefs of the Mexica people also disseminated further into Central and South America. In other modern-day countries like Honduras and Guatemala, the same cultural staples of the Mexica or their derivatives can be seen. This geographic and temporal diffusion enables readers of texts like Birth and Death of the Fifth Age to get a deeper, more integral understanding of why people and societies are the way the are today. Additionally, by seeing how ancient cultures developed and what shaped them, the same methods of extrapolation and reasoning can be applied to the future of such peoples. By knowing what the people of a nation believe in and put weight in, how they react and what decisions they make become more certain. The applications of such predictive methods are undeniably beneficial and spanning; it can shape government policies to be more effective, improve relations with distinctly different nations, or even resolve or prevent internal conflict.

These practical applications of analysis and prediction demonstrate that the merit of dated texts such as Birth and Death of the Fifth Age goes well beyond any surface-level material. Not only are readers disposed to a complex and deep-seated understanding of the culture at hand, the Mexica in this case, but are enabled to make analyses of contemporary and future circumstances. As with any primary document of this nature, it demands further examination and in doing so, a greater picture of the piece’s creators, their descendants, and even humanity is revealed.

Bibliography

Sahagun, B. (1950). “Birth and death of the fifth age.” General history of the things of New Spain: The Sun, Moon, and Stars, and the Binding of the Years(Vol. 7). (A. J. O. Anderson, & C. E. Dibble, Trans.). School of American Research Book.