Slavery, Democratization, and International Conflict in Humanistic Bioarchaeology

by Jacob Euster

This paper synthesizes a variety of sources in its argument for the connection between growing New World democracies and the proliferation of slavery around the world. Using bioarchaeological studies of the skeletons of interred slaves in archaeological sites, this paper illustrates the symbiotic relationship between early democracy and slavery and demonstrates the infeasibility of the two staying intertwined as the definition of democracy evolved. I make use of sources from a variety of locations in the New World and stitch them together into the paper. The tone used throughout is humanistic and, therefore, follows a more narrative format. In addition to archaeological evidence, this paper uses historical sources to support its argument. By utilizing the stories of deceased slaves as they are told through their skeletons, coupled with appropriately-aged sources, I establish slavery’s importance to the advent of democracy and its eventual downfall as a program inconsistent with democracy’s most basic principles.

Introduction

Democracy is defined as a form of “government in which the supreme power is vested in the people and exercised by them directly or indirectly.”1 Within a democratic system, the citizens of a country are all represented and given equal protection under the law yet, while entirely contrary to this egalitarian structure, many democracies around the world were initially supported by the system of slavery. Enslavement occurs when one human is considered a transactional item and is therefore treated as property that can be bought, sold, and traded at the owner’s whim. Slavery is a unique form of conflict in that one typically views a conflict as two-sided and as a legitimate contention between the two parties. In the case of slavery, it must be defined differently as a conflict with “the most unremitting despotism on one part [by slavers], and degrading submissions on the other [enslaved].”2 The advent of slavery as an institutional program for countries colonizing the New World presents this practice as one of international conflict. Modern democracies have, by and large, gotten rid of this practice, yet many were built by this arrangement and owe a debt of gratitude to the millions of people who suffered at the hands of others to lay the foundation for our modern world.

While slavery has affected millions internationally, this paper confines its scope to New World slavery and concerns specifically the manipulation and systematic use of African people for the purposes of slavery in the Americas and the Caribbean. I argue that slavery was a system tethered to the beginnings of New World democracies, and I also show how the two were simply not co-existent over time as fledgling democracies developed and refined their understanding of what democracies should look like. As these historical democracies developed, many realized the contradictory nature of practicing slavery within a system that considers all men equal and took steps to “in some measure stop the increase of this great political and moral evil.”2

A disturbing yet consistent trend in antebellum America is the hypocritical attempt to reconcile the practice of slavery with the idealism of democracy. For example, three lines above the previously used quote decrying slavery, the man often considered the founder of American democracy, Thomas Jefferson, extols the “mild treatment” of slaves and speculates that their “wholesome, though course food” will soon lead to a population with the majority slaves2. While leaders decried the practice of slavery, it was an undeniably pivotal convention upon which many countries, notably America, relied to drive their economies as they sought prosperity. In the late 18th century, British Reverend James Ramsay confirmed this symbiotic relationship between slavery and young democracies in his Address on the Proposed Bill for the Abolition of the Slave Trade when he stated that “the public is told … that the very being of Britain depends on the sugar colonies. The writer of this knows their value, and has no wish to lessen their importance, nor to consider them and the mother country as independent of each other.”3

Through Jefferson’s commentary, we can see the young American republic’s unsteady relationship with slavery. Jefferson’s comments were confined to the state of Virginia, yet each state went through similar processes when laying out their slave programs. The state of Georgia’s relationship with slavery was especially contentious, with its early beginnings in 1735 as a British trustee-governed colony that banned slavery, a practice that ran contrary to the founding values of Georgia as a place “where the worthy could work hard and get ahead.”4 Additionally, Georgia’s trustees were concerned that a slave population would rebel and join their threatening southern neighbors, Spanish-occupied Florida, who offered emancipation in exchange for military service. After James Oglethorpe, the primary trustee in charge of Georgia, and its initial founder, defeated the Spanish, however, the threat loomed no more and trustees eventually gave in to pressure from Georgia’s planter class in 1750.5

Commonly held values fragmented in Georgia, with many turning to abolitionism as the contradictions of a slave-based democracy that viewed all people as equal became too much. Groups such as the Highland Scottish and the Salzburger community expressed their desire for slavery’s ban; however, their objections were in vain, and, by 1776, half of the state’s population was enslaved.6

Bioarchaeology and the Study of Slavery

Bioarchaeology is a fast growing field and lends a useful hand in this study. Stojanowski and Duncan define bioarchaeology as “the contextual analysis of biological remains from past societies,” and osteological (bone) analysis of human remains can answer questions that cannot be answered by historical documents or artifacts.7 The human skeleton holds many secrets and, as bioarchaeological techniques advance, researchers are able to deduce more and more about individuals based on their remains. By taking a humanistic bioarchaeological approach to human remains, one can tell the story of the people buried and draw connections between them and modern humans. Humanistic bioarchaeology makes use of a variety of sources, including ones originating through social and natural sciences. Specifically in this paper, this approach will report on the general lives of slaves as they relate to their surroundings, rather than narrow the focus to one specific enslaved individual.

Bioarchaeologists utilize cutting edge technology to deliver results, including the increasing use of stable isotope analysis. Bioarchaeologists can use variations between elements, such as stable carbon and strontium isotopes, to ascertain an individual’s diet as well as his or her movements throughout his or her lifespan. In the case of slavery, stable isotope analysis can be used to determine a slave’s original locale and can make distinctions as detailed as their specific water source (by using stable oxygen isotopes).8 Additionally, a significant amount of time in bioarchaeology is devoted to studying the pathological (i.e., disease) and physical history of an individual. Biological stress markers such as polished bones can confirm continuous labor in life, and a fracture that has been healed likewise evidences that the affected person was able to continue living after his or her fracture. Pits and grooves on a skeleton’s teeth can evince childhood nutritional deficiencies, and worn-away bones can indicate severe skeletal diseases.9 Bioarchaeologists seek out ‘kernels’ of information from these chemical (isotopic) and physical (osteological) markers and, in turn, produce osteobiographies, biographies of individuals based on their skeletal remains. Osteobiographies aid our understanding of past populations and their practices, and they can be utilized as part of a larger narrative.

The Global Nature of Slavery

Determining the Origin of Barbadian and Brazilian Slaves

Situated in the South Caribbean, the island of Barbados was a major player in the New World slave trade. While over 11 million slaves entered the New World over centuries, over 500,000 people were sent to Barbados alone for work.8 Much of our osteological data on the island comes from the Newton Plantation, a widely excavated site that has been studied since the 1970s by Dr. Jerome Handler and Dr. Frederick Lange. The Newton Plantation was primarily used for sugarcane production, and individuals enslaved here were buried in the Newton Plantation Cemetery, a site for osteological analyses. There have been many different studies on the Newton Plantation and its cemetery, and bioarchaeological processes have allowed us to make a variety of deductions about slaves, including their pathological history, mortuary (and social) practices, and the geographic origin of Barbadian slaves.

Researchers believed that the slaves buried in Newton Plantation came from a variety of locations, both near to and far from Barbados, and they relied on isotopic analysis to investigate this. In the case of Newton Plantation, isotopic analysis was used on twenty-five interred individuals twice, first to determine their original locale based on strontium and carbon levels in their teeth. Human teeth, unlike bone, do not remodel consistently over a person’s life-span. Instead, teeth grow at different rates and capture an individual’s specific childhood diet at various stages of development. The final ‘adult’ tooth, the third molar, completes its eruption (from the jaw) in the later teenage years, capping the viability of teeth dating there.8

Strontium-87 (87Sr) is an isotope deriving from decaying rubidium in rocks, and 87Sr levels are tethered to the specific geology of the region. Strontium is slowly taken up by the soil, then by plants and humans, meaning that the original location of a slave’s birthplace can be estimated. The second use of isotopic analysis was performed on the collagen (the main protein in bone) of individuals interred at Newton and targeted the stable carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios in their remains. Carbon is also vital to isotopic analysis based on the ratios of carbon’s isotopes present in different plants. For example, plants with a C3 signature, such as rice, have been known to grow on Africa’s west coast, meaning an individual in Newton exhibiting strong C3 levels in his or her first molar could have been captured by slaveholders operating in that region. Similarly, the differences in stable isotope ratios of 12C and 13C can help researchers determine whether an individual subsisted on a diet with more terrestrial or marine sources.8

Human bones, unlike teeth, remodel at different rates and throughout an individual’s lifetime, allowing the researchers to compare strontium and nitrogen levels between the two and therefore infer the main contents of a slave’s diet from childhood to adulthood. To solidify their strontium analysis findings, Schroeder and his team also analyzed the stable oxygen levels found in the skeleton. These oxygen levels can help determine the body of water from which a person typically drank. Coupled with the strontium data, the team could, with general accuracy, pinpoint the place from which the enslaved person derived.8

Schroeder and his team determined that the Newton slaves came from a variety of locations and were either considered migrants, meaning they were forcibly brought from their homeland to Barbados, or natives, meaning that they were born on the island. The finding of native Barbadian slaves reveals the long-term scale of the slave trade. To be born into slavery on the island meant that one came from a longer ancestral line of slavery. Many slaveholders, desiring more money, split apart slave families and tore children away from their parents; they were likely never reunited. This may have occurred at Newton, where the slaveholders would have valued strong, young slaves for the backbreaking labor of sugarcane production. Schroeder deduced that there were seven interred slaves that were likely first-generation migrants from Africa. While different areas of Africa exhibit similar carbon, oxygen, and strontium ratios, thereby making exact determinations difficult, Schroeder and his team felt confident enough to assert that the seven individuals derived from three different areas in Africa, potentially the Niger basin as well as parts of Senegambia and Nigeria. Analysis of oxygen isotopes points toward these locales being inland and away from the sea.8 Alexander Falconbridge, a British surgeon employed on slave ships and the author of An Account of the Slave Trade on the Coast of Africa (1788), confirms this during his explanation of the purchasing of slaves. Falconbridge explains that, upon the slavers’ arrival in Africa, “the unhappy wretches … [were] bought by the black traders at fairs, which [were] held for that purpose, at the distance of upwards of two hundred miles from the sea coast; and these fairs [were] said to be supplied from an interior part of the country.”10

A second study on the geographic origins of New World slaves centers its focus on the Brazilian leg of the slave trade – one that typically gets overshadowed by North American and Caribbean slavery yet is similarly depraved. Forty percent of all slaves sent to the New World arrived in Brazil, so its importance in the slave trade cannot be understated.11 Slaves entering Brazil mainly arrived in Rio de Janeiro or Salvador, and it is in these two locations that two slave burials were discovered and subsequent analysis conducted.

The Pretos Novos cemetery in Rio de Janeiro contains an estimated 20,000 individuals. It was used as the burial ground for slaves who died during their voyage to Brazil.11 Conditions on slave ships were rough, and the ships were ridden with many diseases. Alexander Falconbridge continues his account here, noting the lack of airflow in the slaveholding quarters and remarking that “the confined air, rendered noxious by the [odor] exhaled from [the slaves’] bodies, and by being repeatedly breathed, soon [produced] fevers and fluxes, which generally [carried] off great numbers of them10.” In another instance, Falconbridge comments on the insufferable nature of the slave-ship, saying that “the deck, that is, the floor of their rooms, was so covered with the blood and mucus which had proceeded from them in consequence of the [disease], that it resembled a slaughter-house.”10

From Falconbridge’s report, it is not difficult to imagine a slave-ship docking in Pretos Novos after a long journey across the Atlantic. As the ship docked in the Brazilian harbor, workers opening the hull of the ship would have found row upon row of chained people, many so battered from the journey that they could have been dead just as easily as they could have been alive. Bodies were quickly stacked on the dock and, potentially to curtail the spread of disease, many of the bodies in Pretos Novos were intentionally burned. Also, many of the skeletons found bear teeth with marks of intentional modification, indicative of their African origin and migrant status.11

The second location in this study is the Sé de Salvador Cathedral in Salvador, and it contains bodies of slaves as well as various representatives of the Brazilian stratification system, including elites. The elites of Salvador were buried within the church, and their tombs contained a variety of goods to reflect their wealth. Slaves, on the other hand, were buried in the courtyard surrounding the church, and their sparse burials are indicative of their lives as slaves to the elite. European conquistadors arrived in the Americas to establish colonies as well as to Christianize the native populations. By burying their slaves at the church, the Portuguese colonists reflect this desire to impart their religion on their ‘subjects’ and to send them to a Christian afterlife.11

Slavery in Brazil was much more expansive, both in size and in the daily uses of slaves, than on Caribbean islands such as Barbados. Slaves arrived in Brazil from many different locations, both from Africa and from the New World, where slaves were continually bought and sold throughout their lives. Bastos and his team analyzed the isotopic ratios (carbon, nitrogen, strontium) found in the dentin and enamel of 41 teeth from both sites to try and determine these locations. It is important to remember that human teeth only offer information on an individual’s early life, allowing Bastos and his research team to draw conclusions on the general location of each slave’s birth. Consistent with the Schroeder findings of Caribbean slave origins in Newton, the findings in Brazil point to a strongly unified system of slavery that gathered ‘resources’ from a variety of locations. These slaves specifically arrived from over 35 African ports, each connected to a network of slave traders both in the New World and in Africa. Many of these networks cut through the heart of Africa, drawing on the indigenous populations living there. Others met their quota through transactions with tribal leaders who sold off their prisoners of war from other tribes. Each slave network was backed by a colonial power, such as Portugal (in Brazil), and the proliferation of slavery in the New World coincided with the era of exploration and the colonies’ desire (and requirement) to produce goods for their metropoles.11

The Pathology of the Enslaved

Infection and Labor at the Newton Plantation

While the process of enslavement and transportation was often deadly, conditions upon arrival were in no way better. Handler and Lange’s early analysis of slaves buried at Newton reveals the panoply of diseases that affected and killed many slaves. They analyzed the data for 146 interred slaves and tracked their pathological history. While infection was the most common reason for mortality in Newton slaves, they further pinpointed tuberculosis as the disease that most affected slaves.12 Shuler ran her own study of 46 interred skeletons against the baseline created by Handler and Lange to determine if there were any differences in the two studies’ findings. Around 41% of the enslaved skeletons studied showed evidence of infectious disease (lesions); however, some lesions healed, meaning that some of the infected people lived with their disease(s) and did not necessarily perish quickly.12

Adult men and women at Newton died at an average age of 19.95 years with women dying much younger (4.74 years) than other enslaved women in bioarchaeological samples.12 While slave women were valued for their reproductive ability, the reproductive rate on Newton plantation was too low (0.0370) to self-sustain the population. The high mortality rate and the age at which slaves perished meant that there was a generally high turnover rate of slaves in Newton. Being situated in the center of the slave triangle gave slave owners a consistent source of new slaves for work in the sugar plantations. Additionally, the large market demand for sugarcane ensured that, economically, Newton Plantation could easily replace its workforce while continuing to make a profit.

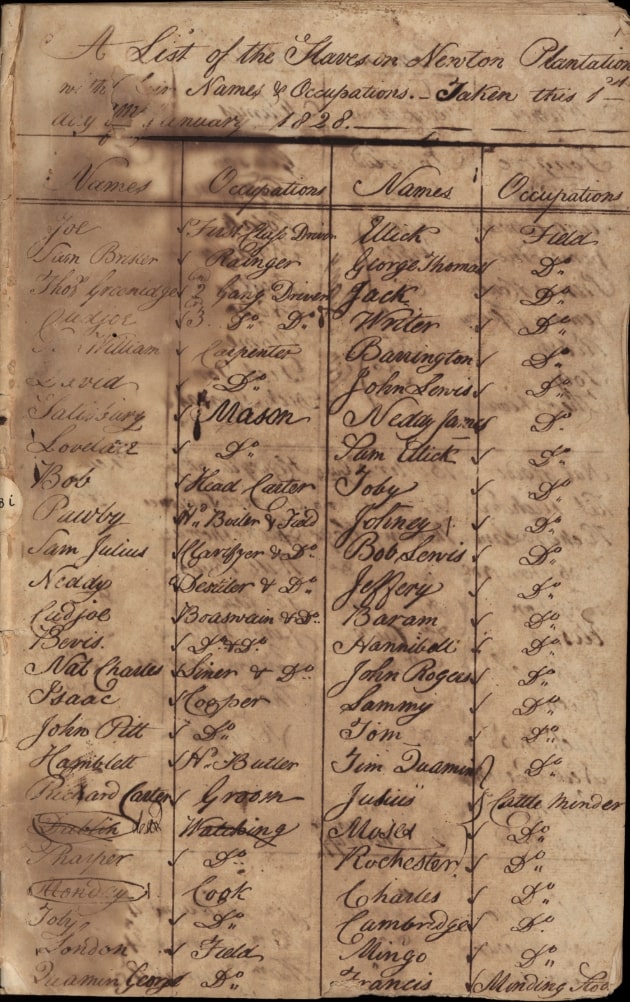

The osteobiographies of these enslaved individuals tells a story of a population overworked and under-supported. Newton plantation records that document the slaves on the plantation in 1828 support this interpretation. Divided into columns with the slaves’ names on one side and their roles on the other, this primary document provides a view of the varied positions occupied by individuals in the plantation. Women, it appears, were generally valued like men and were divided into separate field units for crop production. For example, the female slaves Henrietta and Gracy Ann were relegated to Field 10, while Dolly was the driver (leader) of the Field 4 group. A man named Nat Holder occupied a position as butler in the main house alongside working as a field hand in Field 3.13 On a typical day, Holder would have risen well before sunrise to go out to the sugarcane field. From there, he would have joined a team of slaves in aspects of sugar production, from planting seedlings to harvesting the resilient, bamboo-like sugarcane that required multiple harsh blows for cutting. If the Newton overseers decided to invite guests for a dinner party that night, it was Holder’s responsibility to leave the field well before their arrival to assume his second role as the butler.

This document also includes catalogues of the animals on the farm, complete with their names as well.13 It is an inventory of sorts for the plantation, and the use of names for the slaves was not affectionate but rather practical, in order to differentiate among them. Although slaves made up the bulk of the plantation’s assets, they were considered on paper to be equal to the farm animals. This document paints a bleak picture of the daily realities of the Newton slave experience, and it is an invaluable resource for the study of the Barbadian slave trade.

Photo from the Newton Plantation Collection. Source: http://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:46045

The Subjectivity of Enslavement

It is important to consider the subjectivity of the slave experience on an individual level. While the entirety of the slave class was considered unequal to the freemen, even within the slave class, distinctions were made among individuals. Slave experiences were varied, and a slave’s life on one plantation could be entirely different than a slave’s time on a plantation just a mile down the road. This subjectivity is exhibited at a site in Delaware called Avery’s Rest, a homestead for the Avery family around the turn of the 18th century. There were eleven burials at this site, and DNA testing has revealed that the first eight buried individuals originated from Europe. These eight graves were buried next to each other, and the final three burials, although oriented similarly to the first eight, were buried in a notably different location than the first exhumed graves. Burials 9, 10, and 11 exhibited DNA originating from Africa, and the three bodies found were from two adult men and a young child. Each of them had DNA distinct from each other, meaning they were not related. African slave-ships made many stops along their routes, both in Africa and in the New World, often forcibly tearing apart families and mixing enslaved populations and, therefore, genotypic information.14

Consider the mundanity of a slave’s daily life – waking early each morning and working extremely hard all day, only to retire at night to repeat the process again the next morning. When allowed by the slave owner, slaves could break up this monotony in a variety of ways, by singing spirituals or by such pastimes as tobacco use. The site at Avery’s Rest continues to yield information and specifically offers a perspective on the leisure activities of the slaves buried there. The two adult Africans buried at the site exhibit tooth wear similar to their European-based owners. In particular, they showed signs of deliberate tooth wear caused by the resting of a tobacco pipe on the molars. Burial 9 contained an individual age dated to approximately 32-42 years of age. Burial 10 contained a skeleton aged to approximately 22 years old. The person in burial 9 was clearly older than the other buried slave, and he lived a life of hard labor based on his extreme joint wear. One could reasonably conclude that, if both individuals exhibit pipe wear, the older slave would show more wear, but this is not the case. Burial 10, although much younger than burial 9, showed four well-worn grooves in his molars (from resting a pipe), while burial 9 only exhibited one slightly worn groove.14

Here the subjectivity of the slave experience is narrowed down to individuals, even on a small-scale operation like at Avery’s Rest. Unfortunately, records of Avery’s Rest are not available, thus one cannot currently know the true meaning behind this difference between the two slaves. There are two possible explanations that one can offer. First, the older slave was presumably with the family for a longer time yet showed fewer signs of pipe wear on his teeth. Combined with the heavy molar wear of the younger slave, one could conclude that the slave-owner did not at first allow tobacco use by his slaves. Tobacco was introduced to slaves either as an incentive to motivate better work or out of a fraternal bond based on a changing, more positive mentality towards slaves. Second, there is also the possibility of a small-scale stratification system in which one slave was valued above the others and, therefore, better treated. For example, the younger slave could have been more expensive and valuable than the older slave at Avery’s Rest and, therefore, afforded more luxuries to keep him relatively satisfied and compliant. Dietary trends, based on isotope analysis, show that the three enslaved individuals ate a different diet than their owners, including less animal protein and less nutritionally useful foods, such as maize. Even within the small settlement of Avery’s Rest, slaves were segregated, both in dietary allowances as well as in mortuary practices.

Photo by Kate D. Sherwood, Smithsonian Institution. Source: https://www.delawareonline.com/story/news/local/2017/12/05/rehoboth-discovery-may-change-delaware-history/898848001/

Mortuary Ritualism in New World Slavery

Modern conversations regarding slavery tend to narrow its scope to the American South, but osteological evidence tells of an America vastly different from this familiar label. While Avery’s Rest was a small-scale northern site of slavery, excavations prior to construction in Manhattan in the 1990s revealed a massive cemetery with a burial population of up to 20,000 African-based individuals, all victims of the global program of slavery that connected the North with the South, North America with the Caribbean and Latin America, and the New World with the Old World.15 The possibilities surrounding the African Burial Ground are vast, but I discuss it here in terms of slave mortuary practices.

As Africans transitioned to life in the New World, they preserved much of their original culture through their mortuary rituals. Death was a unique period for slave-slaveholder relations, and “slaveowners usually allowed their [slaves] to bury their dead with some small measure of dignity.”16 Over time, however, slaveowners identified slaves’ drawn-out, processional funerals as hotbeds for insurrection. Gabriel’s Rebellion, a small revolt in Richmond, Virginia, in 1800, was planned at the burial of an infant slave. As tensions grew, white slaveowners increasingly attended and sometimes funded slaves’ funerals; they did this mainly out of fear of violent conflict though occasionally because of legitimate empathy towards their deceased slaves.16 Almost 92% of the slaves buried at the African Burial Ground in New York City were buried in coffins, and the account book of local woodworker Joshua Delaplaine contains descriptions of purchase orders, all from white men and purchased for slave funerals. Many of the written descriptions here detail the purchase of a coffin for “his negro man.”16

There are two burials in the African Burial Ground that merit inclusion in this paper. The most expensive coffin found in the site was the burial numbered 176. The coffin had six iron handles on the sides, two of which were elaborately wrought. Additionally, sixty metal tacks were found pressed into the coffin. While this man, aged 22-24, was honored in death, potentially by his owner, his bones exhibit wear typical of a slave sentenced to hard labor. Periostitis (infection of the bone) and hypertrophy (enlarged bone due to repeated stress) indicate a man who engaged in hard labor for an extended portion of his life.15 Additionally, the presence of facial lesions is characteristic of nutritional stress, and overall osteological analysis shows that this man lived the life of a typical slave. Nevertheless, he was buried as if he were a free man.15

One of the oldest bodies found at the African Burial Ground was that of a 55-60 year old man, buried with a unique set of items. These items link the New World slaves to their original culture in Africa. In central Africa, Congolese people revere certain people known as nganga, whose role is to collect minkisi or bundles of various items such as leaves, rocks, and rings. The nganga uses these bundles to engage with spirits and to activate the properties contained within the bundles. This man was buried with such bundles and, considering his old age, would have gathered the respect and knowledge necessary to engage in these practices. Unfortunately, his osteology points toward a man who, like the Burial 176, was revered in death yet subjected to hard labor in life.15 Regardless, these two burials show that African mortuary practices and traditional cultural practices were both feared and, on some levels, respected by white slaveowners. Allowing Africans to continue their cultural practices as slaves would have offered slaves some comfort and would presumably have made slaves more manageable. It is important to remember that most slave-owners were outnumbered by their slaves, underscoring the possibility of violent uprising at any moment. Only through the combination of careful concessions to slaves, as well as systematic racism and fear, could these potential insurgencies be quelled.

Further preservation of African mortuary culture is also present in the Newton cemetery in Barbados. While the addition of burial items can shed light on the lives of a deceased person, exclusion can tell a lot as well. There are a few mounds within the site, some of which naturally reflect the topography of the region while others contained burials. The largest mound found in Newton Plantation contained a single skeleton, burial 9, whereas the smaller mounds contained layers of skeletons indicating repeated use as a burial site.17 The skeleton, once a young woman in her twenties, was buried haphazardly in a pit much too small for the body and was the only body found to be buried face down in a prone position. The mound in which she was found dated older than the other, more populated mounds, raising questions as to why her grave was undisturbed. She was buried without a coffin or items, suggesting she was held in low esteem by other slaves.

Researchers conducted lead-analysis on the individual in burial 9 and found that her lead levels were almost double the mean levels of the others interred at the cemetery. Considering all the evidence (the prone, solitary burial; lack of goods; the high lead content), Handler and his team considered a scenario in which the slave community viewed this woman negatively. She was likely afflicted with lead poisoning, which would have resulted in bizarre symptoms that could have been viewed as supernatural and evil.17 Jack Goody found in his ethnographic study of West African burial techniques in 1962, that burial mounds are reserved for high-status individuals or those convicted of evil acts, such as witchcraft. Coupled with her prone position facing downwards, which could have been conducted in a similar African manner so that she would be disoriented when she awoke from the dead, led the researchers to surmise that this woman was believed to have been a witch or other evil person. The burial mound was used to prevent the deceased person from coming into contact with the earth, the “guardian of the living,” thereby tainting the activities of the living.17 The continued practice of a variety of African mortuary rituals throughout the New World supports the notion that slave-traders drew upon a multitude of African resources in the global slave trade.

Conclusion

The development of New World slavery coincides with the development of democratic principles around the world. Slavery in the New World took hold as colonial powers flexed their muscles and raced not only to populate but to produce in the Americas. Slavery was a function that spurred the development of the New World, but the practice could not continue indefinitely. Holding one person subservient to another is contrary to democratic ideas, and the practice could not coexist with democracy in a rapidly developing world.. This tension was famously brought to a head in the American Civil War, in which abolitionism and morality won, but only after a centuries-long development of democratic values which slowly loosened the grip that slavery had on colonial powers. While conflicts are typically conceptualized in terms of relatively equal powers competing over a set period of time, slavery unravels this narrative by showing in a new light how conflict could involve inequality and sustained abuse. The kidnapping and transporting of slaves to the New World makes this an inherently international conflict, one incompatible with democratic ideas of mutual prosperity and equality. Bioarchaeology is a field that can add a lot to our understanding of the world and the connections between the human body and its surroundings. Presenting these osteobiographies in a humanistic light gives the narrative depth and meaning, and it aids in the transfer of perspectives from a historic to a modern sense. As contemporary humans in the New World, it is vital that we seek out the perspectives of degraded individuals, especially those enslaved here so that we can truly gain an understanding of their experiences. In doing so, we will reflect on the atrocities that were committed and the progress (and faults) we have made toward social equality so that we may, optimally, pursue ways in which we can eradicate such atrocities in our own time.

References

- “Democracy.” Merriam-Webster. Merriam-Webster, 2018. Web. 4 April 2018.

- Jefferson, T., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 2016. Notes on the State of Virginia. 87, 162.

- Ramsay, James. An Address on the Proposed Bill for the Abolition of the Slave Trade : Humbly Submitted to the Consideration of the Legislature. London : Printed and sold by James Phillips, 1788.

- McIlvenna, Noeleen. The Short Life of Free Georgia : Class and Slavery in the Colonial South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

- Wood, Betty. “Slavery in Colonial Georgia.” New Georgia Encyclopedia. 24 September 2014. Web. 20 September 2018.

- Young, Jeffrey R. “Slavery in Antebellum Georgia.” New Georgia Encyclopedia. 26 July 2017. Web. 20 September 2018.

- Stojanowski, C. M., & Duncan, W. N. 2015. Engaging Bodies in the Public Imagination: Bioarchaeology as Social Science, Science, and Humanities. American Journal of Human Biology, 27, 51-60.

- Schroeder, H., O’Connell, C., Evans, J. A., Shuler, K. A., & Hedges, R. E. M. 2009. Trans-Atlantic Slavery: Isotopic Evidence for Forced Migration to Barbados. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 139, 547-557.

- Roberts, Charlotte A., & Keith Manchester. The Archaeology of Disease. Ithaca, N.Y. : Cornell University Press, 2005., 2005.

- Falconbridge, Alexander. An Account of the Slave Trade on the Coast of Africa. By Alexander Falconbridge, Late Surgeon in the African Trade. Eighteenth Century Collections Online, British Library, 1788.

- Bastos, M.Q.R., Santos, R.V., de Souza, S.M.F.M., Rodrigues-Carvalho, C., Tykot, R.H. Cook, D.C., & Santos, R.V. 2016. Isotopic study of geographic origins and diet of enslaved Africans buried in two Brazilian cemeteries. Journal of Archaeological Science, 70, 82-90.

- Shuler, K. A. 2009. Life and Death on a Barbadian Sugar Plantation: Historic and Bioarchaeological View of Infection and Mortality at Newton Plantation. J. Osteoarchaeol, 21, 66-81.

- “Newton Plantation Slave List 1828.” Lowcountry Digital Library, Newton Plantation Collection, lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:46045.

- Owsley, D., Bruwelheide, K. S., & Barca, K. G. 2017. Osteological Examination of Burials from the Avery’s Rest Site, 75-G-57.

- Frohne, A. E. 2015. The African Burial Ground in New York City: Memory, Spirituality, and Space. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

- Smith, S. E. 2010. To Serve the Living: Funeral Directors and the African American Way of Death. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Handler, J. S. 1996. A Prone Burial from a Plantation Slave Cemetery in Barbados, West Indies: Possible Evidence for an African-Type Witch or Other Negatively Viewed Person. Historical Archaeology, 30, 76-86.

Acknowledgments: I would like to thank my course instructor, Dr. Laurie Reitsema, as well as my TA, Samm Holder, for their support throughout this entire process. From the beginning of this assignment to its continuation as a potentially published piece, they have been there to offer guidance whenever needed. I appreciate the opportunity that they, as well as the The Classic, have given me with this paper and I know that I would not have been nearly as successful without their guidance. I would also like to thank Dr. John Inscoe from the History department, for his guidance and thoughts regarding my paper. Dr. Inscoe played a large role in developing this paper from a class assignment to a legitimate paper.

Citation style: AJPA

. . . . . . . . . . Return to the Table of Contents.