David Ligare: A Post-Modern Resurgence of the Classical Ideal

by Benjamin Thrash

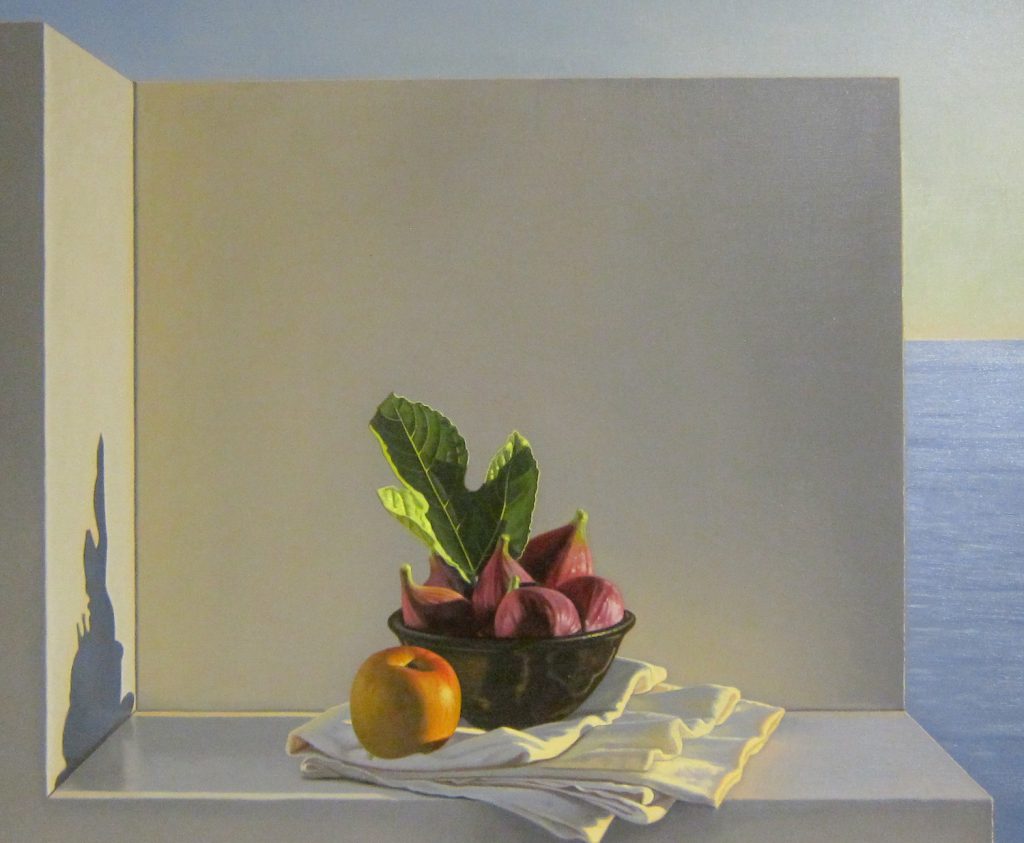

Source: David Ligare, Still-life with Figs, 1997 by Sharon Mollerus is licensed under CC BY 2.0

The artist discussed in this essay is driven to create the “literate picture,” a type of art in which every minute detail is a kind of clue to deciphering the painting’s moral message.1 Much of contemporary art is ostentatious and inaccessible to the public, but Ligare’s work is decidedly more democratic. In his time as an intern at the Georgia Museum of Art, the writer had the opportunity to spend many hours with this artist’s work and attend a gallery talk. Here, he clarifies the artist’s visual vocabulary for those less familiar with visual analysis. This work investigates the three primary genres of Ligare’s work to demonstrate consistent themes.

Art Historical Context

In its pastoral beauty, David Ligare’s work bears an immediate visual resonance with Homeric Greece. He fuses the modern and the antique, synthesizing a new ideal that celebrates both tradition and contemporary society. In a time when contemporary art is often abstract and non-representational, Ligare pulls from traditional representations of landscapes, still lifes, and nude figures. Much like the artists of the Italian renaissance, Ligare realizes that society’s need of “a renewed desire for knowledge,” and he seeks to elevate the viewer’s intellectual growth by means of the literate picture.2`

The Renaissance marked a period of humanism, a philosophical movement in which artists and thinkers praised the intellectual and creative potential of man. Michelangelo epitomized humanism in his works by synthesizing contemporary religion with the renewal of classical themes. Ligare’s paintings function similarly: he creates ideals and synthesizes classical themes with objects indicative of modern society. His work is not entirely in keeping with that of the Renaissance artists who inspired him though. He paints from live models (i.e. inherently contemporaneous subjects) rather than the works of antique sculptures, and he refrains from conforming Greek and Roman mythology to Catholicism, a significant departure from the practices of Renaissance artists. The freedom to do so speaks volumes about the vastly different context of art-making six centuries ago when every aspect of peoples’ lives was dictated by religious authority figures.

Ligare’s work deviates from both the modern and the antique because he employs unfashionable representational means and dated subjects while remaining unrestricted by the religious norms that directed old masters’ work. His themes are not only unfashionable but highly susceptible to criticism as the contemporary art world intentionally tries to separate itself from its Euro-centric history. Ligare may be one of the few genuine postmodernists remaining because his work continues to function in dialogue with his art historical roots whereas others intentionally attempt to separate their work from tradition. Despite his unmistakable alignment with classical tradition within Western culture, Ligare has thrived in the modern art world because he finds an equilibrium between relevance and irrelevance.

I believe Ligare’s relevance is rooted in the simple power of beauty. Through beauty, he is able to create the sustained interest needed to relay underlying themes and concepts. The public that is uninformed about art history can be intimidated by work that is so entrenched in elitist concepts that it becomes irrelevant to their lives. Many postmodern art objects are simply talking points for artists to explicate their genius, and this is to the detriment of making connections with most viewers. Ligare’s work is even more compelling because of how rare it is to be exposed to something that we can understand solely through representational imagery. His work also speaks towards universal, timeless truths and is therefore innately available to all. Ligare’s work is essentially democratic, and it is intended to educate the community to become well-rounded members of society.

Although Renaissance artists were inspired by the masters of marble, their homages to antiquity fell short because the work was dominated by Catholicism, which required a rejection of Greek mythology (i.e. paganism). Ligare, however, remains true to Greek and Roman culture, depicting scenes of Hercules, Patroclus, Orpheus, and Achilles that directly refer to the work of classical masters. His most elaborate reference to Greek mythology is through the seated figure, Penelope. Described as “a still point in a turning world,” Penelope is the ever-faithful, ever-patient wife of legendary Odysseus from the Homeric epics, The Iliad and The Odyssey.3 In The Odyssey, she waits twenty years through dauntless waves of suitors while Odysseus braves many challenges on his way home from the Trojan War. Penelope offers a connection to antiquity with a rare degree of detail provided by surviving texts from that period.

Penelope (Fig. 1) marks a momentous shift in Ligare’s career. In contrast to prior work such as his Thrown Drapery series (Fig. 2), the visual presence of a figure makes the piece decidedly more humanistic and opens it to a more engrossing interaction with the viewer. Ligare continues to showcase his mastery of fabric within her clothing, making the connection with an established practice. Typical of his work, the fabric connotes the antique by resembling a toga even though the model and the fabric are contemporary.

Fig. 1. David Ligare, Penelope, 1980, oil on canvas, collection of the artist. View here.

Fig. 2. David Ligare, Naxos (Thrown Drapery), 1978, oil on canvas, private collection in New York City, New York. View here.

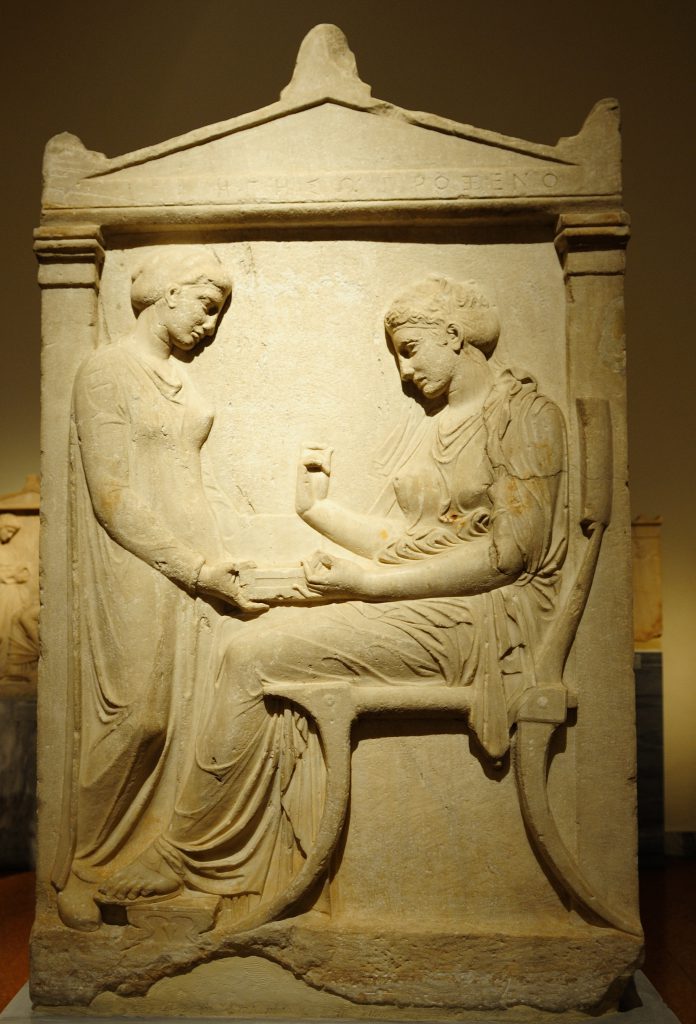

Similarly, the chair on which she sits mimics the Funerary Stele of Hegeso (Fig. 3), but the material and assemblage of the chair indicate modern manufacturing. The reference to the funerary stele also furthers dialogue about the role of and respect for women at this time. The inanimate chair seems to respond to Penelope with its own life. The curvaceous backing caresses her figure and creates a sense of movement in a statuary environment. The bulge of the seat accentuates her visual weight and provides a physical and emotional presence to the figure it supports. Her physicality abates within the wispy folds of her white dress, but as the light shines through, Penelope’s solidity becomes one with her enigmatic repose.

Fig. 3. Callimachus, Funerary Stele of Hegeso, marble, c.410 – 400 B.C., Athens, National Archeological Museum. Image attribution: “Grave stele” by Luca Cerabona is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Like the gaze in Hiram Powers’ sculpture The Greek Slave (Fig. 4), Penelope’s meditative demeanor operates as the gateway to an empathetic relationship with her suffering. Both Powers and Ligare engage with a rich history of sculpted women, but they have also recontexualized classical influences to suit their purposes. The Greek slave looks away and submits to her viewers with a downward gaze, but Penelope’s gaze is upright and assertively looking beyond the viewer. Her solemn contemplation immediately grapples with the emotions one might have had before encountering the piece, and the level seascape offers a tranquil environment in which to ruminate with her. In contrast to the wrathful waves that pushed Odysseus off course, the seascape mirrors her serenity.

Fig. 4. Hiram Powers, The Greek Slave, 1851, marble, Yale University Art Galleries. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

Several factors evidence the inward nature of her thoughts, and it is interesting to observe the subtle changes in the graphite sketches provided next to the painting in the exhibition at the Georgia Museum of Art. Most notably, Ligare sketched a woman who faced the viewer and sat with an open posture, clearly indicating the outward nature of her thoughts. Painting Penelope’s hands in her lap and having her gaze beyond the viewer into the distance emphasizes the internalization of her struggles. Ligare also emphasizes Penelope’s contemplative face through the perspectival system established by the tiled floor: he uses one-point perspective so that the orthogonal lines point to her face. As seen in Raphael’s fresco The School of Athens (Fig. 5), it was common practice during the Renaissance to use lines of perspective to point towards significant features. Considering that faces naturally attract a viewer’s attention, it would be redundant to point towards her face once again. Another aspect of the classical tradition lies in the study of philosophers like Plato and Aristotle, so I believe Ligare points not toward her face but toward her psyche.

Fig. 5. Raphael, The School of Athens, 1509 – 1511, fresco, Apostolic Palace, Vatican City. Attribution: Raphael [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

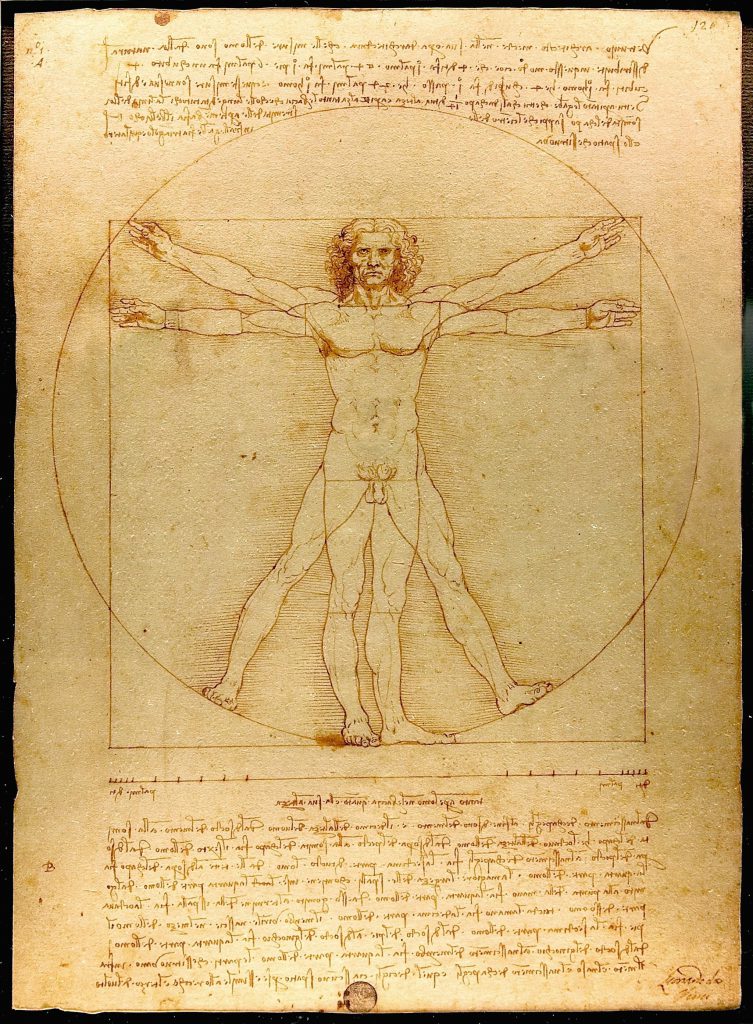

Fig. 6. Da Vinci, The Vitruvian Man, c. 1490, Pen and ink with wash over metalpoint on paper, Venice, Galleria dell’Accademia. Attribution: Gallerie dell’Accademia [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Still Lifes

Although his still lifes lack the immediate narrative resonance of his figures, Ligare very thoughtfully chooses his objects and their lighting to expand the potential of this underused practice. If classical figures were uncommon in a contemporary gallery space, traditional still lifes are twice as rare. Still, Ligare is able to keep them relevant because he creates allegory in the way his objects burst with meaning specific to Greek myths, like mementos of heroic journeys.

Referring to The Odyssey once again, Still Life with Grape Juice and Sandwiches (Fig. 8) alludes to the Greek custom of xenia. Directly translated as “guest-friendship,” xenia refers to the tradition of hospitality in which hosts would treat weary travelers with the utmost generosity, and guests would return the favor with the utmost courtesy.5 Integral to this practice is the offering of wine and bread, and many times throughout Odysseus’ journey, he is provided these very substances. Ligare pulls from this deeply rooted ritual and re-contextualizes it with contemporary objects. Instead of rich wine and authentic loaves, he presents a pitcher of ordinary grape juice and a heap of bologna sandwiches on insubstantial bread.

Fig. 8. David Ligare, Still Life with Grape Juice and Sandwiches, 1994, oil on canvas, private collection in San Francisco, California. View here.

Ligare was inspired by his time serving in a soup kitchen for the homeless in Salinas, California.6 There is something that resonates in the difference between homeless people today, with whom most people avoid eye-contact, and the homeless travelers of ancient Greece who were treated just short of gods. The Greeks had a well-developed sense of humanity that influenced Ligare and Renaissance artists alike.7 Though the xenia of today functions in a dramatically different context, the heartfelt connection the artist felt with the homeless he was serving is evident. The most unsettling divergence between the antique tradition and its modern equivalent is how the giving of food has become the most menial offering, the minimum sustenance for life in an increasingly arduous world.

Ligare’s still lifes feel as though they have a life of their own. Still lifes have historically been divided into two categories: memento mori, which emphasize the remembrance of death, and vanitas, which deal with the transience or even futility of life. The light of a setting sun soaks into the objects in Still Life with Grape Juice and Sandwiches, simultaneously filling them with life and foreshadowing the lack thereof. Food often connotes the preservation of life and provokes a feeling of hope but with a subconscious understanding that it will eventually spoil. The ephemerality of food parallels that of a human life.

In Still Life with Grape Juice and Sandwiches (Fig. 8.), food has a particularly poetic quality in the way it functions as both a core component of life and an object that conveys love and camaraderie. Some of the earliest paintings can be found in the tombs of affluent Grecians (Fig. 9), and they frequently depict the sharing of wine and bread at a symposium, a communal event at which men and boys drank wine, discussed philosophy, and played games to celebrate life. Ligare accesses this tradition from antiquity while also capitalizing on the sacramental quality of wine and bread in Christianity, framing it in a kind of modern altar. The Greeks frequently made offerings to the gods in celebration of prosperity, and the stage on which the juice and sandwiches sit doubles as an altar in which ordinary objects gain religious significance.8

Fig. 9. Unknown Artist, from Tomb of the Diver, c. 470 B.C., fresco, Campania, Italy. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Originally a pragmatic solution to a compositional problem, the box fulfills several artistic purposes.9 Primarily, he sought a controlled space in which to conduct rigorous investigations of the objects, reminiscent of Leonardo da Vinci’s rigorous investigation of anatomy.10 The box also fosters a “harmony of wholeness,” as the artist puts it, which continues the goal of old masters like Giorgio Vasari.1 The marble box provides a space of measured precision matched only by the sculpture and architecture of Hellenism. The sharp geometry could also refer to the resurgence of antique structures during the Renaissance, such as columns and arches. Furthermore, the simulation of marble that defines and controls the space speaks about Ligare’s virtuosity in painting. During the Renaissance, it was much cheaper to paint walls to simulate decorative marble rather than installing the real thing, so it became common practice to exercise illusionistic skills.

The enigmatic, sterile background creates a sense of isolation akin to surrealism, but it merely acts as a medium through which to emphasize the allegorical potential of common objects like grape juice and sandwiches. Whether the painting refers to the continuation of xenia, the practice of the Christian Eucharist, or the simple act of giving food to the homeless, Ligare capitalizes on the plurality of meaning and expands the boundaries of still life painting by dramatizing the shifting meaning of recurring objects.

Landscapes

As seen in his still-life and figure paintings, Ligare aligns himself to classical Greece through narrative figures and symbolic objects, but landscape paintings – in the strictest sense – focus exclusively on scenery. How does the artist uphold his distinctive oeuvre while preserving the pure beauty of a virgin landscape? The Renaissance and classical Greece offer little assistance here because landscape painting was almost non-existent in Greece, and landscapes in the Renaissance served only as contextual backdrops for Catholic, figure-dominated images. There is, however, a rich history of American landscape painting that gives him a visual vocabulary to work with. Westward expansion of the United States, commonly known as manifest destiny, was seen as a directive from God, and the paintings of Albert Bierstadt, Thomas Cole, and Frederic Church (of the Hudson River school) almost functioned as spiritual propaganda for the promised land. Although not explicitly stated with crosses, holy figures, or sacred objects, American painters were able to speak a holy truth through rivers, mountains, trees, and the like. Ligare uses the vocabulary his predecessors established to speak the timeless truths from antiquity without overt symbols.12

It is nearly impossible to present a landscape as definitively Greek without muddying the environment with the people or structures of their civilization. Nonetheless, as is typical of the artist, Ligare finds the most delicate balance between the civilization and natural purity. It is difficult to choose a single landscape of his that summarizes all of his broad explorations, but In Praise of Italy (Fig. 10) best encompasses his nuances in landscape painting.

Fig. 10. David Ligare, In Praise of Italy, 1987, oil on canvas, private collection in Los Angeles, California. View here.

The title makes a very forthright and purposeful statement, but viewers familiar with Ligare’s work understand that the image before them derives from the California landscape with which he grew up. Alluding to antiquity through architecture in landscape painting is nothing new, but his dedication to the practice in the twenty-first century is unconventional. The comparison of the modern world to that of antiquity, especially on his scale of operation, sets him apart from his contemporaries.

Alluding to Virgil’s epic, agricultural poem, The Georgics, Ligare literally frames the painting in the words of its most famous passage, Laudes Italiae (Praises of Italy).13 It reads, “Perpetual Spring our happy climate sees: Twice breed the cattle, and twice bear the trees; And summer suns recede by slow degrees.”14 Ligare aligns his work with antiquity by visually manifesting the literature of that time: the brilliance of the mid-day sun radiates over two cattle and a tree wrapped in vines. Continuing with the theme of fusing the modern and the antique, he also manifests the sensations inspired by a twentieth century poem about California, “The Tower beyond Tragedy.”15 Written by the American poet Robinson Jeffers, it reads:

On the cheek of the round stone . . . they have not made words

For it, to go behind things, beyond hours and ages,

And be all things in all time, in their returns and passages, in the

Motionless and timeless center16

Ligare creates a sense of timelessness by referring to a Roman poet whose words continually resonate even in the modern world. He compromises the purity of a virgin landscape with plowed land and a distant structure, but he deemphasizes humanity’s influence by excluding figures, presenting it as an abstract force and denying viewers the opportunity to fabricate a narrative. Moreover, the civilization reestablishes the sense of a place frozen in time, when man and nature coexisted in beautiful harmony. Jeffers’ writing primarily refers to the omnipresence and persistence of nature, and In Praise of Italy speaks truth about the timeless character of a pastoral landscape.

As mentioned before, Ligare has a rich history of landscape painting to draw upon for inspiration, particularly with Yosemite Valley in California. Like his predecessor Asher B. Durand, Ligare fabricates his own brand of secular spirituality – not unlike the still life discussed before – engulfing the viewer in a temple of foliage. His absorbing attention to the specifics of the ideal reinforces the significance of nature’s every detail, and the controlled handling of paint has the potential to clarify emotional epiphany. Some of his earliest works – hyper-realistic drawings of marks made in the sand – foreshadow his lifelong fascination with nature. Ligare finds Californian coast is especially inspiring as a meeting place of shifting seas and steadfast shore, and he believes the strength of California’s rocky shoreline foretells a future as long and great as that of Greece.

He continues his comparison through the unifying presence of the ocean, saying, “Because California actually looks so much like Italy, Greece, and Spain . . . and because its earliest European immigrants were from the Mediterranean, it seems fitting to substitute one for the other.”17 Although In Praise of Italy does not show the shore, the idea that the water will eventually reach the Pacific Ocean is embedded in the meandering river. Its winding creates an “S” curve that complements the weaving and folding sensation established by the layered mountain ranges. Ligare reiterates this weaving with the grape vines, gracefully entwining two forms of life, and their ephemerality is contrasted by the rigid, lifeless boulder. The tree is also tied with rope, a subtle signature of the artist, whose name means “to bind” in Latin. It is through these kinds of subtleties that Ligare creates the literate picture, and the careful interpretation of this landscape results in a rewarding understanding of a kind of visual puzzle.

A Resurgence of the Classical Ideal

Ligare separates himself from Renaissance and Greek art by painting a figureless landscape, but he perpetuates their idealism. Longing for the reemergence of emotionally compelling and didactic art, he makes real the classical ideals to spawn insight into the truth created by beauty, and genuine beauty is timeless. He has reinvented classicism with greater authenticity than Renaissance artists, and his prestige in the modern art world testifies to its immortal influence. Unifying Ligare’s body of work is the eternal daylight which never subsides: his works are both living images stuck in antiquity and stills of theatrical narratives. It is difficult not to feel moved by the optimistic serenity he invents, and though a full appreciation is reserved for those versed in Greek mythology, its secular spirituality is compelling. David Ligare demonstrates something foreign to the sterile and abrasive texture of modern art, a more enlightening and positive ideal, and his successful rendition of Greek culture elucidates the reality that pursuing outmoded practices does not sacrifice the progress of modernity.

Bibliography

Clemens, David. The Importance of David Ligare: Art that Thinks and the Gravity of Our Own Time. thenationalreview.com. https://www.nationalreview.com/phi-beta-cons/david-ligare-art-education-importance/ (accessed April 4, 2018)

Jeffers, Robinson. The Tower Beyond Tragedy. poemhunter.com. https://www.poemhunter.com/poem/the-tower-beyond-tragedy/ (accessed April 4, 2018)

Ligare, David. “Writings: On Perspective.” Davidligare.com. http://www.davidligare.com/essays.html (accessed April 4, 2018)

Scott Shields, David Rodes, and Patricia Junker, David Ligare: California Classicist. London: Papadakis Publications, 2015. Exhibition Catalogue.

Stull, Richard. Literate Landscapes: David Ligare’s Ancient Greco-Roman Oil Paintings. artistsnetwork.com. https://www.artistsnetwork.com/art-mediums/oil-painting/literate-landscapes-david-ligares-ancient-greco-roman-oil-paintings/ (accessed April 4, 2018)

Notes

1 Ligare, David. “Writings: On Perspective.” Davidligare.com. http://www.davidligare.com/essays.html (accessed April 4, 2018)

2 Scott Shields, David Rodes, and Patricia Junker, David Ligare: California Classicist (London: Papadakis Publications, 2015), 23.

3 Ibid., 52.

4 Ibid., 53.

5 Ibid., 116.

6 Ibid., 121.

7 Stull, Richard. Literate Landscapes: David Ligare’s Ancient Greco-Roman Oil Paintings. www.artistsnetwork.com. https://www.artistsnetwork.com/art-mediums/oil-painting/literate-landscapes-david-ligares-ancient-greco-roman-oil-paintings/ (accessed April 4, 2018)

8 Stull, Richard. Literate Landscapes: David Ligare’s Ancient Greco-Roman Oil Paintings. www.artistsnetwork.com. https://www.artistsnetwork.com/art-mediums/oil-painting/literate-landscapes-david-ligares-ancient-greco-roman-oil-paintings/ (accessed April 4, 2018)

9 Conversation with the artist, April 2016.

10 Ibid.

11 Shields, Rodes, and Junker, 121.

12 Clemens, David. The Importance of David Ligare: Art that Thinks and the Gravity of Our Own Time. www.thenationalreview.com. https://www.nationalreview.com/phi-beta-cons/david-ligare-art-education-importance/ (accessed April 4, 2018)

13 Ibid., 101.

14 Ibid., 103.

15 Ibid., 103.

16 Full poem can be found at: https://www.poemhunter.com/poem/the-tower-beyond-tragedy/

17 Ibid., 105.

Acknowledgments: I work mostly through what is visually available, but I am indebted to the work of Scott A. Shield, David Rodes, and Patricia Junker for their work on David Ligare: California Classicist, as much of my knowledge and direction came from their catalogue. To Hillary Brown, for unparalleled guidance and knowledge during two years as her intern, thank you.

Citation style: Chicago